Sen. Mitt Romney’s Fourth of July essay at The Atlantic was mostly unremarkable and frequently correct. Ours is a country in thrall to wishful thinking, the Utah Republican said, to believing “what we hope to be the case” rather than what is actually the case, and thereby refusing to address real and growing problems.

But one portion, in which Romney prescribed a remedy for “our national malady of denial, deceit, and distrust” was strikingly, tellingly wrong.

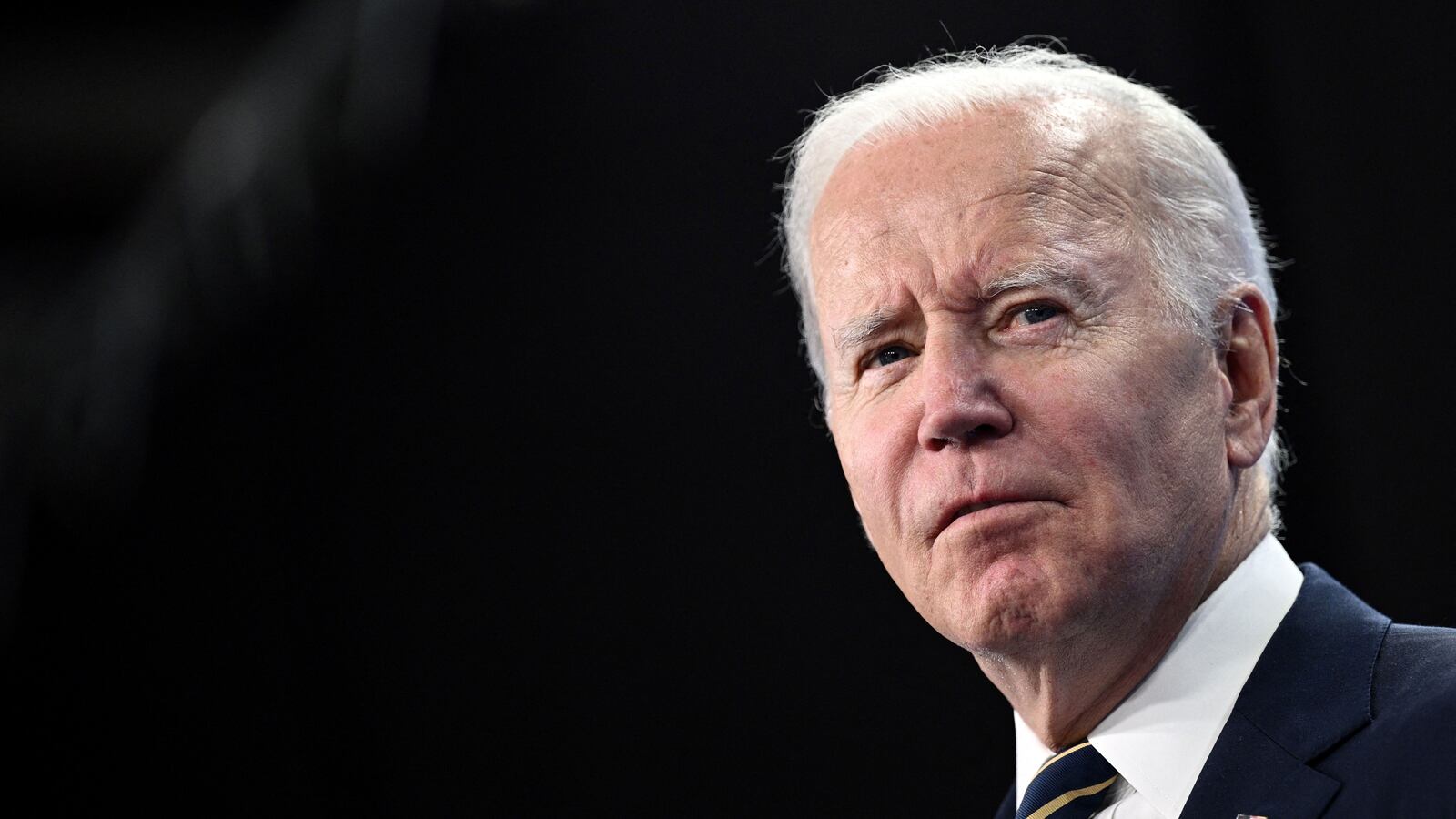

What we need, he asserted, is a good president, someone more energetic, perhaps, than President Joe Biden—but certainly not former President Donald Trump. “I hope for a president who can rise above the din to unite us behind the truth,” Romney wrote. Yet he also offered, as a stopgap, the prospect of ordinary Americans rising “above ourselves—above our grievances and resentments.” Eventually our presidential savior will fix us, but “[w]hile we wait,” kind and responsible behavior from normal people will have to suffice.

Romney is far from the first to express this hope, nor will he be the last. Waiting for just the right president to come along and solve everything is a popular American hobby. Biden himself promised to be that president in 2020, telling supporters in Georgia shortly before the election that though “divisions,” “anger and suspicion are growing, and our wounds are getting deeper,” he’d work to “restore our soul and save our country.”

Well, maybe he tried. And maybe Romney actually believes what he wrote, as implausible as it is coming from a senator and erstwhile presidential nominee who knows full well our government’s capacities and, more important, its limitations. But the rest of us should be under no such delusion.

It’s true, another four years of Trump would exacerbate our confusion and distrust. But it’s absurd, even naïve, to imagine that if we can just get a better president everything will be fine. That’s not how presidents work. It’s not how people and polities work. It may be “what we hope to be the case,” but it isn’t the reality at hand.

The reality is the presidency is at once too powerful and too impotent to fulfill these hopes. The power of the office is a detriment because it makes the role too valuable a prize. Partisan animosities scale up with executive authority, and that all but guarantees we’ll elect “a divider, not a uniter,” to tweak another former president’s phrase. But even if we did elect some anodyne candidate, someone so mild Biden looks spicy by comparison—well, what could that president do? There are ever fewer things beyond the reach of executive power, but the human heart is among them. No president can make us turn away from denial, deceit, and distrust.

In fact, presidents and other large-scale solutions may be uniquely disadvantaged when it comes to fixing Americans’ troubles with trust and truth. Top-down interventions to steer people away from groundless suspicion and false beliefs—like the Biden administration’s short-lived Disinformation Governance Board—tend to exacerbate these ills rather than abate them. What are they trying to hide?—the thinking goes. We must be onto something if they're responding like this.

Such interventions also tend to confuse the source of our social and informational chaos. A disinfo board goes after content, but the supply of content shouldn’t be our main concern. That’s not to absolve social media companies of responsibility for what appears in their networks, but it is to say lies and divisive insinuations are primarily a demand-side conundrum. “The problem isn’t that there are liars,” as author Freddie deBoer has argued, because “there will always be liars. The problem is that people believe them… It has to start with the believers, not with the belief.”

Unfortunately, for those still holding out hope for one big fix, the only believer you’re guaranteed to affect is yourself. You can change your own behavior, limiting your content consumption in quality and quantity alike; cultivating intellectual virtues of studiousness, honesty, and wisdom; making sure you regularly touch grass. You might be able to influence your family and friends to do likewise. But you can’t make everyone change how they function as believers. You can’t control their hopes and fears and habits. And neither can a president or Congress or Mark Zuckerberg or the best AI content moderator in the world.

Our “denial, deceit, and distrust” has gotten into the American esprit de corps, yes, but it has also gotten into us individually and so must be individually addressed.

That’s not to say nothing will improve, absent an unprecedented American lurch into practical virtue. Some of the present tension we feel will subside on its own as we adjust to what are still very new media. Two decades of widespread internet use feels interminable, but as a period of introduction of a world-changing mode of communication, it’s not very long. Our national malady is real, but we may also be mistaking growing pains for its symptoms. The introduction of the printing press was tumultuous as well—it was among a handful of new technologies that “changed the whole face and state of things throughout the world,” wrote the philosopher Francis Bacon in 1620. The prospect of the printed word justifiably raised fears of strife, war, and revolution. Half a millennium later, we’re no longer panicked over books, but we are, alas, still stuck living through history.

And from history we should take one more lesson, too: Our expectation of getting “back to normal” is almost certainly unfounded. That kind of fix doesn’t exist. The political “normal” most of us have in mind is the post-war consensus, a period of several decades in the middle of the 20th century (in the U.S. and elsewhere) in which the public and lawmakers alike were historically unpolarized.

That wasn’t normal, though. It was anomalous compared to prior decades of U.S. history, and it probably isn’t coming back. It shouldn’t be our baseline model of political health—even if we get a good president.