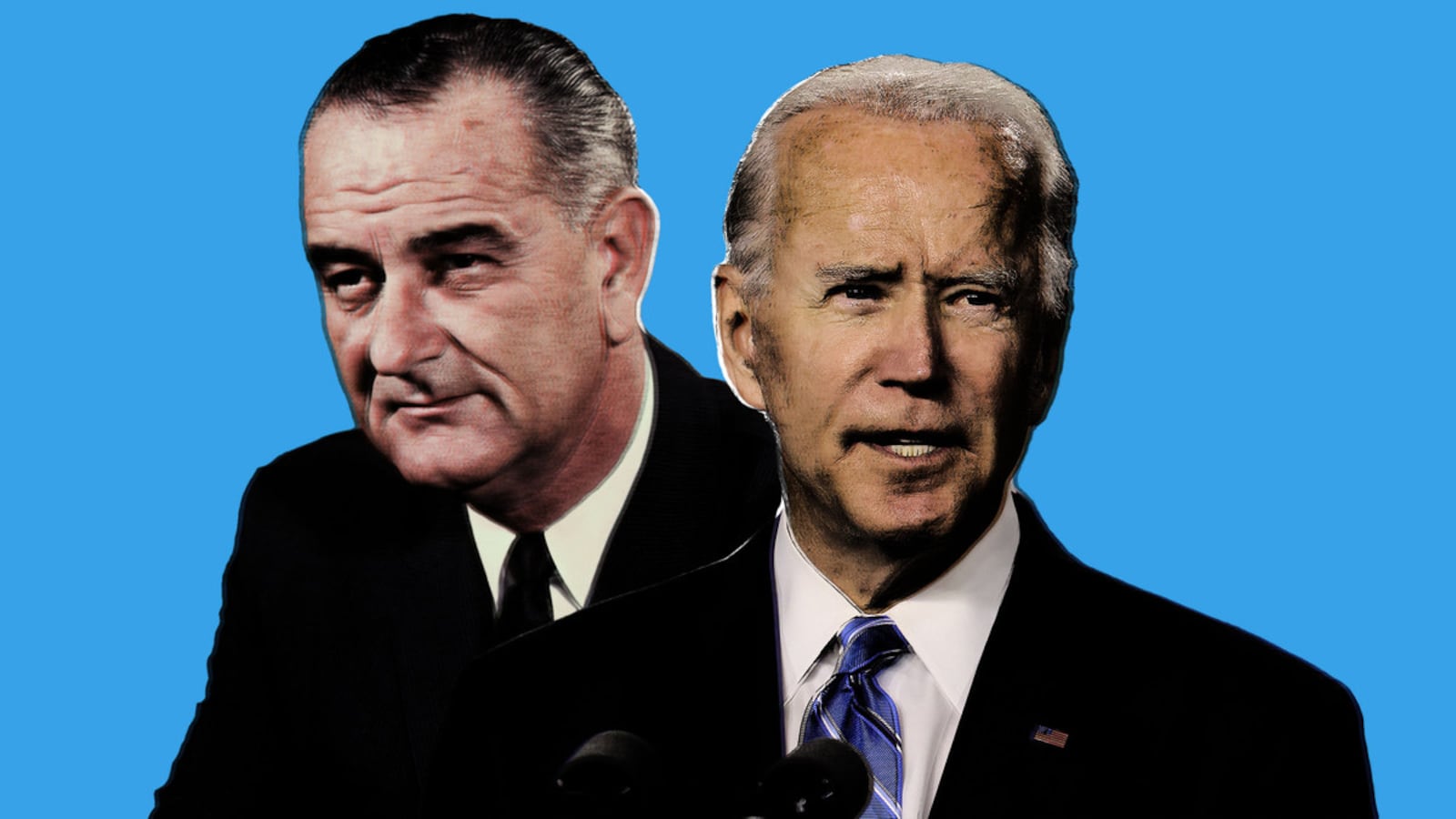

“The federal government fought the war on poverty,” Ronald Reagan once quipped, “and poverty won.” He was slamming Lyndon Johnson—one of the men to whom Joe Biden has been frequently compared. Reagan’s comments indicated that the Great Society, however noble its aspirations, not only failed but also led to unintended negative consequences. Biden faces some of the same perils from his attempts to dramatically reframe the size and scope of government, via the $1.9 trillion COVID-relief bill and his $2 trillion infrastructure plan.

The writer and linguist John McWhorter captured this sentiment about some of the unintended consequences of the Great Society well, writing in 2007 that “the Great Society sowed the seeds for a Black identity based on being bad, and treating it as enlightened to pull poor Black women out of the job market and pay them to have children instead. Generations of young people grew up in fatherless communities in which full-time employment—i.e., conformity to a long-established American norm—was rare.” The Biden administration’s recent move toward unwinding the practice of requiring people to work or perform public service to receive Medicaid coverage is indicative of how Biden policies risk evoking a similar backlash: a well-intended idea that somehow perpetuates dependency.

Even those who believe LBJ laid the groundwork for a more compassionate nation have to concede that the Great Society promised “an end to poverty and racial injustice,” which makes it, by definition, a failure. It was also an electoral loser for decades. Although Vietnam was the primary culprit, Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan were both elected, at least in part, because voters wanted law and order amidst a rising crime rate and heightened cultural anxiety and urban unrest. There was also the sense that the welfare state was too large and that big government liberalism had overreached its mandate.

What is indisputable is that Johnson’s presidency ended on such a sour note that he couldn’t even run for re-election. His approval rating was a mere 36 percent. Managers of the 1972 Democratic convention “made sure Johnson’s picture was absent among the portraits of former standard bearers Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, Adlai Stevenson and John F. Kennedy,” according to Boston University Professor Bruce J. Schulman, author of The Seventies.

Fast-forward to 2021: Joe Biden is riding high, and LBJ is back in vogue—as are many of the same issues he championed (in a sense, an ironic reminder of his failure to fix them). Voting rights and civil rights are front-page news. Police shootings and threats of riots abound. And we are spending money that would have made LBJ blush. Years of congressional gridlock and stasis have caused many to yearn for a “master of the Senate” who can steamroll the opposition and pass landmark legislation. Does Biden have what it takes to finally right our sinking ship?

I’ve said that I think Biden is capable of being a consequential president who changes the trajectory of American politics. And he is. I’m willing to believe it’s possible that it will all work out and it will turn out that (as Dick Cheney said) “deficits don’t matter.” Maybe we can simply keep spending money without the chickens ever coming home to roost. Maybe all the things conservatives warn will happen when you start giving people other people’s money will turn out to be overwrought or antiquated. And maybe nothing crazy will happen on Biden’s watch to undermine his domestic accomplishments. But when it comes to wanting to be the next LBJ, Biden should be careful what he wishes for. Don’t forget, LBJ was riding high when he crushed Barry Goldwater in 1964. The world has a way of intervening.

Johnson’s defenders will rightly cite his failure in Vietnam (“Hey, hey, LBJ, how many boys did you kill today?”) as a key reason his legacy was, for so many years, tarnished. This is true, but it should also serve as a warning that presidents don’t control their agenda or their fate. Consider a few of today’s looming challenges. As I write this, we are spending trillions of dollars on stimulus, and we are on the verge of spending trillions more on “infrastructure.” We are living in a precarious experiment (can we simply keep spending and shoulder high levels of debt?). This huge spending spree might cause inflation, and tax hikes could hit the economy at a perilous time.

But wait! There’s more: We’ve reached the point where the vaccine supply outstrips demand. Will we get to herd immunity? What about variants? The murder rate is up. Biden has no plans for the border crisis, and (for better or worse) his progressive base just pushed him into accepting more refugees. The Iranians are enriching uranium, and Israel is trying to stop them. China is playing rough with Taiwan. There’s a giant Russian army on the Ukrainian border. Syria is still a disaster. North and South Korea are in an arms race.

Biden hopes to avoid repeating history by ensuring that Afghanistan won’t be his Vietnam. But history doesn’t repeat, it rhymes—and the Afghanistan withdrawal could be his “fall of Saigon.” What will the Taliban do to the Afghan security forces? What if, by leaving behind interpreters and others who have put their lives on the line for America, we are just hanging them out to dry? What else will the Taliban do, and who will it harbor? And could that undermine all of Biden’s domestic accomplishments (ironically, like Vietnam did to LBJ)?

Even if Biden avoids all of those dangers, Johnson’s legacy remains flawed. Biden might think he can simply give up on the war in Afghanistan, but the war on poverty is the real “forever war.” As the progressive outlet Mother Jones noted a few years ago, “The government’s official measure of poverty shows that poverty has actually increased slightly since the Johnson administration, rising from 14.2 percent in 1967 to 15 percent in 2012” (although if you include “additional non-cash government aid from safety net programs,” the poverty rate fell during that time). It is impressive that LBJ enacted nearly 200 new laws in such a short timespan. That copious output, coupled with its enduring legacy (Medicaid and Medicare, for example), make Johnson a consequential president. They do not, however, make him a good one. If the goal was to win the war on poverty, we didn’t achieve it—we are still stuck in a quagmire.

So what can Biden learn from Johnson’s mistakes? The big parallel is that LBJ set inordinately high expectations domestically that he just couldn’t meet. He obviously fell short of ending poverty and racism. Biden runs a similar risk of not meeting similarly high expectations.

For so many reasons, Lyndon Johnson’s presidency should serve as a cautionary tale to Biden, not as an aspirational goal. We should all cross our fingers that his wish doesn’t come true.