Paris might seem a long way to go for mashed potatoes, but in 1985 that plebeian dish is exactly what drew me there as a critic for Time magazine

And not only for mashed potatoes—A.K.A. pommes purée—but to sample the fare that won the chef-proprietor Joël Robuchon’s elegantly glowing 16th arrondissement restaurant, Jamin, three Michelin stars in as many years.

Considered a step forward from the cuisine dubbed “nouvelle,” Robuchon’s innovative culinary style was most often labeled “moderne” or “courante,” as in trendy, which it indeed became. Long after Jamin closed, and with an international chain of his L’Atelier de Joël Robuchon, he amassed more than 30 Michelin stars—more than any other chef on earth, and in 1990 was dubbed one of the Chefs of the Century in the Gault & Millau guide.

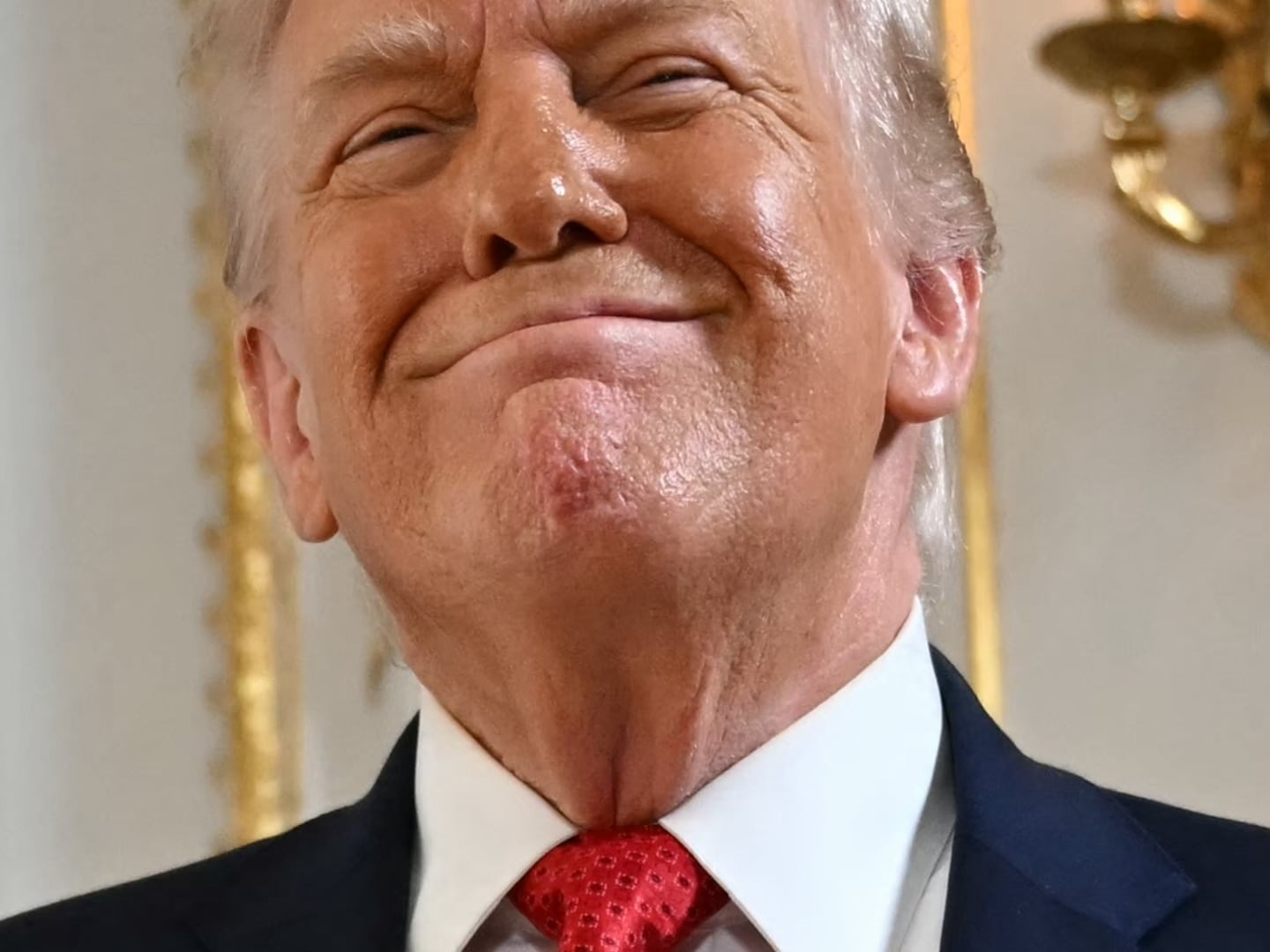

Learning of his death from cancer in Geneva on Monday at 73, I look back with a mixture of joy and sadness as I recall the two days I spent in his restaurant and kitchen thirty-three years ago. There, his elegant inventions were realized by a kitchen staff of 18 while in the dining room 30 servers coddled 45 diners. The whole time his wife, Janine, kept an eye on the checks. A seemingly shy and courtly man (he was even given to kissing a lady’s hand by way of greeting) and with a generally rosy cherubic demeanor, he could become a dogged master as he insisted upon his staff’s exactitude, not only in cooking, but in realizing the colorful pointillist dots of herbs, sauces and vegetables that garnished and enhanced his dishes. As intricate as those jewel-like decorations where, Robuchon’s philosophy was simple: “It is important to respect the integrity of the ingredients by preserving their flavors and aromas,” he told me. Certainly, the recipe for his storied potatoes is simple as it calls for one pound of butter to be whisked into one pound of cooked, peeled and puréed potatoes, with a dash of salt and a drizzle of milk or cream to achieve the airy chiffon texture.

If mashed potatoes was his most iconic triumph, I recall even more sustaining specialties in offerings such as canette rosée, a juicily braised and roasted crisp skinned duckling that he enhanced with an Asian spicing of cinnamon, nutmeg, ginger, anise and coriander. His version of the classic tête de cochon, presented a silky gelatin that shimmered around bits of tender pork head meat, sprightly with parsley and shallots. But of all the things I sampled, none made as much of an impression as his poulet en vessie, young chicken, its breast skin underlined with slices of black truffles all poached in an aromatic broth held within the vessie—a pig’s bladder. And when the vessie was opened...Oddly, I am embarrassed to say, I critiqued that dish then as needing a little more salt!

One of the surprises in that kitchen was a somewhat removed station where I spied plastic bags filled with food floating in a slow-simmering bath. Boil-in-the-bag at Jamin, I asked? Turns out long before we ever heard the term “sous-vide,” the inventive Robuchon was perfecting prepared portioned meals for first-class passengers on the French railway’s Paris to Strasbourg route.

In later years, I was to sample Robuchon’s even more modern moderne at his first counter restaurant in the lobby of the Pont Royal Hotel where I often stayed, and still later at the Four Seasons Hotel in New York, where we had a happy reunion. Being something of a procrastinator, I failed to try his latest L’Atelier across from New York’s Chelsea Market and I doubt that I ever will now, if indeed it even continues.

Having grown up fairly poor and at loose ends in the French city of Poitiers, Robuchon slowly found his way to the kitchen via years of working menial training jobs. When I asked him about a small Lincoln-like figure that appeared on the Jamin menu looking like a wayfarer, he explained it was a compagnon, an itinerant apprentice in the French tradition that he had performed. “I am a compagnon, and will always be one,” he said.

So one can only hope that his next apprenticeship will be at the Pearly Gates Café where he will surely blithe the angels with an innovative Cuisine Céleste.