The resurgence of vinyl in recent years has caused nostalgia among generations of Americans, with many seeking to replace the records they still associate with their years growing up. This has led to a boom in the second-hand market for 45s and LPs of every genre.

The majority of these records, of course, are not in the least rare—a million seller did exactly what it said after all. (The first of these, surprisingly, occurred all the way back in 1902, a Caruso opera that likely would not fare so well today).

But, as with all collectables, there are sub-genres that operate by different rules, and one of these is the world of rare Rhythm and Blues recordings. And if these are the sounds you ever listen to, even if you merely buy a compilation album or choose a podcast, you are a beneficiary of John Anderson’s legacy, whether you have ever heard of him or not.

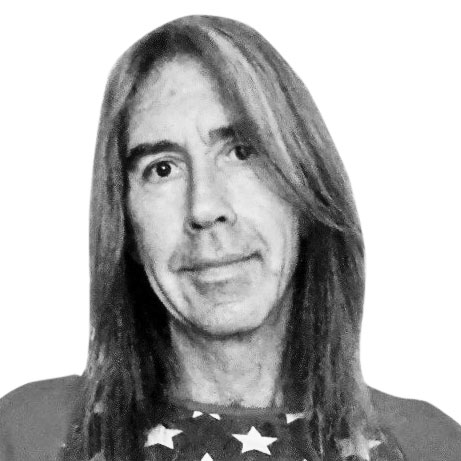

To fully comprehend the importance of Anderson, who died Oct. 2 at the age of 70, you have to understand where he came from and the scene he helped foster—sometimes, it seemed, especially in the beginning—almost by himself.

Whichever town or city you grew up in, you can be assured that back in the ’50s and ’60s there were local record labels in those places. Record labels you’ve never heard of. And with good reason—these tiny labels without the ability to get airplay or distribution were usually restricted to small pressings that rarely broke out of a local market. Just a few hundred were often made, and copies were even given away free at performances by the singer or band.

Some of these labels sold white artists: Teen and rock and roll and garage bands abounded. But many were R'n'B or soul or funk. And in those cases, a small market grew even smaller, because the color barrier meant that they often did not have a chance to cross over racially either. Successes did happen, sure. The wonders of Motown or James Brown proved impossible to contain. But they were outnumbered by the vast majority of artists and recordings that never came close to breaking through to a wider audience.

But while American audiences, with exceptions, remained ignorant of this small-label bounty, a group of young people in the U.K. were starting to realize that despite the complete lack of sales or recognition, many of these records were truly amazing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jwsZDC9iMiA

There was a throwaway line in a Rolling Stone or Creem article a good many years ago: “The British are the librarians of America’s music heritage.” The history of this goes back a long way: The Stones, the Beatles, the Animals, all were feverish fans of R'n'B, and all embraced it live and in their own recordings. And they communicated this devotion to their fans. In the U.K., the fans invented a term for this music that has no equivalent in the U.S.: Northern Soul.

Coined at the start of the ’70s, Northern Soul referred to the fact that clubs, usually in the North of England, had become hugely popular playing beyond-obscure American soul records, and the biggest attraction bar none for this audience was being introduced to unknown sounds. As a result, copies of new discoveries would change hands for sums that for the time were hard to grasp—a week’s wages for a single 45 would be handed over without hesitation. Inevitably, some record dealers grasped the potential, and through the door ahead of everyone else was John Anderson.

As a young music fan growing up in the post-war ’60s tenements of the notoriously grim Pollok estate in Glasgow, John was already trawling the local stores when he happened upon a local camera shop with a roomful of unwanted records. He offered 3d (old pence, Britain was still pre-decimal then) for each, then promptly resold them in one swoop for 6d and a 50-year career had begun.

Back then, overseas travel was an expensive adventure into the unknown. Regardless, after just one more local deal, John immediately knew the logical next step was going to the source by traveling to the States. A month later, his parents in their council house front room watched in dismay as a truck with 60,000 soul singles arrived at their door. This was just the start. All over America, warehouses, radio stations, and music stores were one-stop shops full of unsold, unwanted, and basically unvalued records that were not sold individually but by the pallet or the ton by owners more than happy to offload them. One notorious seller on the West Coast, when put into bankruptcy by the IRS, handed over the keys to his warehouses of R'n'B records as settlement (he quietly kept aside all his stock by white artists, believing that was where the value was, and at the time he was likely making a good decision).

All of this made John’s world essentially a volume business. In 1977 alone he shipped over a million 45s back to storage locations in the UK run by his wife, Marisa, and their helpers. He had a thriving mail-order business by then. Lists would go out by mail to every soul fan in the country, many of whom recall endless attempts to reach John on the lone phone number he worked from to try to get one of the highlighted rarities on the front page of his newsletter, only to be told “Sorry, it’s gone!” when they finally got through. He even started his own record label, Grapevine, to reissue some of the records proving both popular and elusive and had solid success with those.

But mostly he was on the road in the U.S., four months a year or more from coast to coast and back again. His stories from those days of the people he dealt with—the promoters, the artists, the hucksters and jivers and just plain crooks (many labels were used for money laundering, and the industry overall had a lot of people it was wise not to be on the wrong side of)—were endless and should have been better recorded.

Regardless of his travels, John remained a dedicated family man, living primarily in England, but still very much a proud Scotsman, with Tunnocks Teacakes, Irn Bru and a good whiskey all part of his DNA. More importantly for his business dealings, he was endlessly fair, not least in understanding that the intrinsic value of something went far beyond a $ sign. “What’s it worth to you?” was the usual question, the long game instinctively something he always knew was the best choice.

There’s no real way to emphasize just how much present-day collections world-wide and the knowledge of America’s soul recordings would otherwise be lost or diminished but for John’s constant toiling over the years. The huge troves he shipped home containing new discoveries of those early days are now few and far between, but to this day there are still hundreds upon hundreds of sought-after titles with just a few known copies surviving, and the number of these that came from his endless sourcing is almost ridiculous.

The time for more wide-spread appreciation of these recordings seems to have finally arrived. Reissue labels such as Numero Group thrive. Artists who’ve made it safely to this day with voice intact who are still recording, like Betty Lavette, have gone from footnotes to Grammy nominations. Jack White purchased one of the three known copies of an unissued Motown 45, Frank Wilson’s “Do I Love You,” and repressed it for Record Store Day in 2018. Type almost any title into YouTube, and magically a scan of the label will appear and the record will play at your whim. It’s easy to be oblivious to the fact that you may be looking at one of the two or three copies ever found.

Prices on eBay make for a good measuring stick of this in simplest value terms. Take for example Fluorescent Smogg, a now in-demand ’70s obscurity. John once reminisced about having had 100 copies of it on hand back when he’d bought out the label’s complete deadstock. But being unable to generate any demand for it at the time, he used the records to literally prop open a door before throwing away most of them, just disseminating a few remaining in the “Soul Packs” he’d offer of uk10 for 100 random 45s. A single copy of the 45 sold in recent times for $7,410—more materialistic types would likely endlessly bemoan the notional loss. John just smiled laconically as he told the story.

Last weekend a semi-annual pilgrimage took place: The Allentown 45/78 RPM show is a widely anticipated event in the record-collecting universe. Although not the largest record fair in the world (that honor belongs to Utrecht) or even in the U.S. (that takes place in Austin), it only admits dealers selling vinyl in 45 or 78 form—no LPs, CDs, or other formats. So, for serious record collectors it’s close to the top of the tree.

Needless to say John was a familiar figure there over the years, casting an avuncular eye over the proceedings, greeting old friends—that of course meant pretty much everyone there—and offering wry comments on the offerings. It was hard after all to surprise a man who at one time or another had seen copies of almost every record in the room pass through his hands. Regardless, the thrill of the chase never left him. So, everyone there last weekend sharing stories of treasured finds that had come from him was in accord that he still attended in spirit—the man who, with no fanfare, became the greatest soul record dealer in history.

Michael Robinson is the co-organizer of the Dig Deeper concert series bringing obscure '60s soul musicians to the stage in New York City.