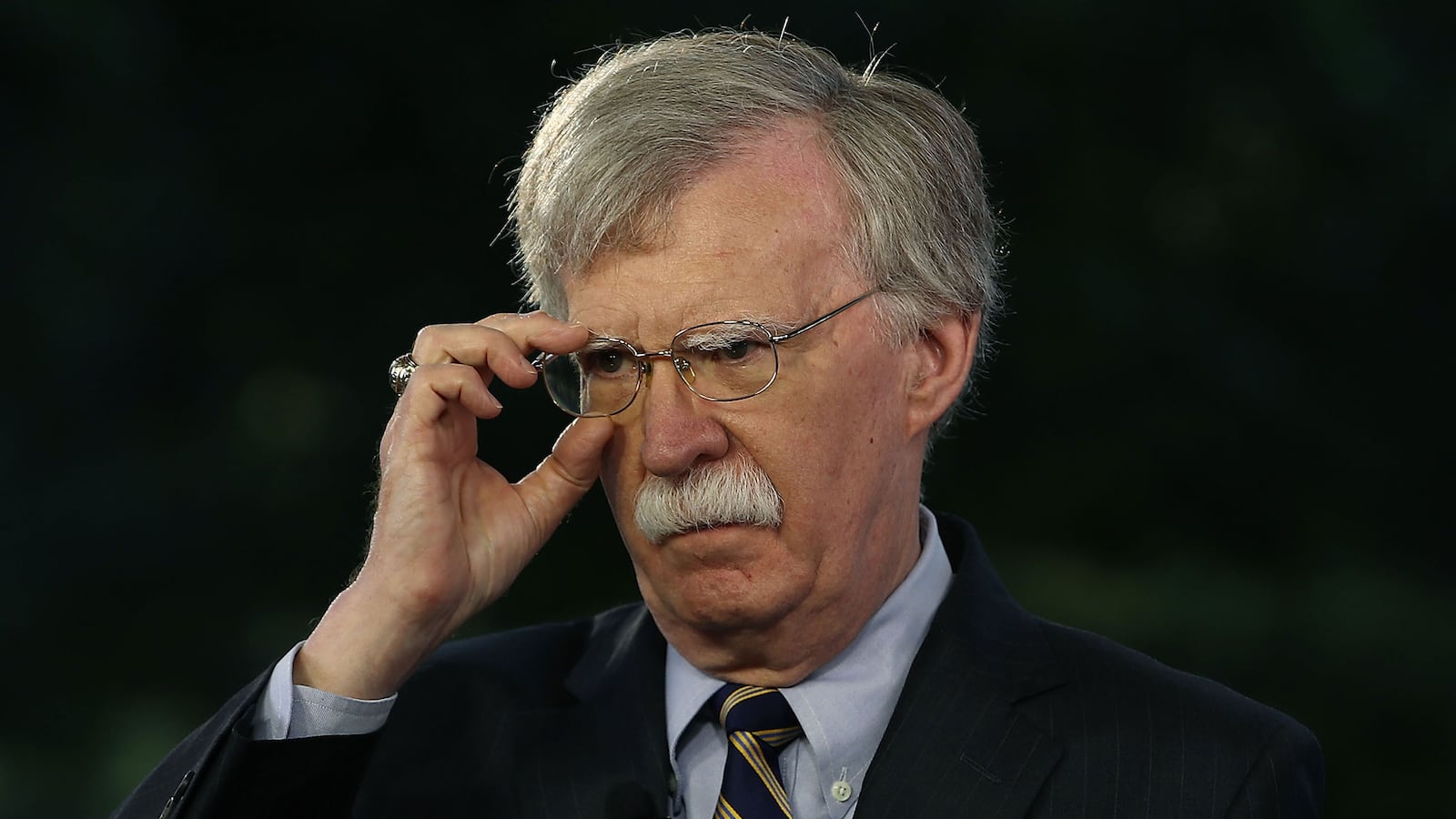

National Security Adviser John Bolton might just have gotten his wish: President Donald Trump has called off the June 12 summit meeting in Singapore with North Korean leader Kim Jong Un. For weeks, Bolton has been working to set impossibly high expectations for the summit.

Bolton appeared to be willing to settle for nothing other than Kim showing up to Singapore to turn over the keys to his nuclear program—which North Korea has recently taken to calling its “treasured sword”—to the United States. Bolton’s preferred model all this time has been the 2003 disarmament of Libya, which at the time had a nuclear-weapons program that was effectively in a primordial state and was dismantled by the United States.

When North Korea hears of this “Libya model,” it recoils. For Pyongyang, the lesson of Muammar Gaddafi’s decision to enter into a process of disarmament was what came eight years later—when Libyan rebels found and mutilated him, aided and abetted by Western airpower. It is precisely to avoid this fate that North Korea was determined to cling to its nuclear weapons.

If one were to pin down the exact moment all momentum toward the high-stakes summit effectively evaporated, it might have been last week, when Trump, speaking off-the-cuff, conflated Bolton’s 2003 “Libya model” with the 2011 air campaign led by the Obama administration—the very action that precipitated Gaddafi’s downfall.

“In Libya, we decimated that country,” Trump said, adding that “that model would take place if we don’t make a deal [with North Korea], most likely.” This was nothing short of an overt threat to bring about Kim Jong Un’s end should he not show up in Singapore prepared to prove his nuclear-weapons program was shut down for good. Trump might not have a nonproliferation scholar’s grasp of history, but his conflation of the 2003 and 2011 “Libya models” was ultimately the moment to destroy the summit.

Two high-profile statements by North Korea in the past week—one attributed to the country’s vice foreign minister, Kim Kye Gwan, and another attributed to Choe Son Hui, a vice minister in the North Korean foreign ministry—took aim at Bolton and Vice President Mike Pence over their comments. It’s the latter statement that the White House cited in its letter canceling the summit meeting.

Choe’s statement, calling Pence a “political dummy,” would have been entirely avoidable had the vice president not decided that he needed to go on Fox News to reiterate Trump’s threat to give Kim the Gaddafi treatment if the administration didn’t get its pie-in-the-sky denuclearization deal.

There’s a clear line here: Bolton’s Libya talk sets expectations for Trump, who slips up and threatens North Korea with regime change, which leads to Pence defending Trump, which leads to North Korea lashing out, which leads to Trump canceling the summit. The dysfunction within this administration in the lead-up to this meeting ultimately brought the summit crashing down.

The North Koreans, in the meantime, have kept their position static and have been more than willing to communicate what they were willing to offer up; not once did any authoritative North Korean statement indicate any interest in denuclearization as the White House imagined it.

Trump has left a way out. In his Thursday letter canceling the summit, he tells Kim that if he changes his mind and calls or writes the White House, the meeting could be rescheduled. In effect, the president is inviting Kim Jong Un to grovel for the chance to meet to discuss his own disarmament. There’s little evidence the sky-high expectations that the administration set up going into the summit have been modified.

The summit’s cancellation may be for the better, as long as Trump finds that he has sufficiently saved face by being the one to call off the meeting. Yes, Kim may now return to his old ways and test short-, medium-, and intermediate-range ballistic missiles—he’s announced a moratorium on intercontinental-range ballistic missile tests—but a one-on-one Trump-Kim meeting never made much sense.

Diplomacy with North Korea was never going to be easy and a summit, something Kim's family has long sought, should have been positioned as a reward to North Korea if they had entered a prolonged and phased process with the United States, built on the back of expertise and staff work over months of diplomacy. Kim and Trump may yet meet some day, but for now, the task for the White House is to stop the Korean Peninsula lurch toward a devastating conflict.