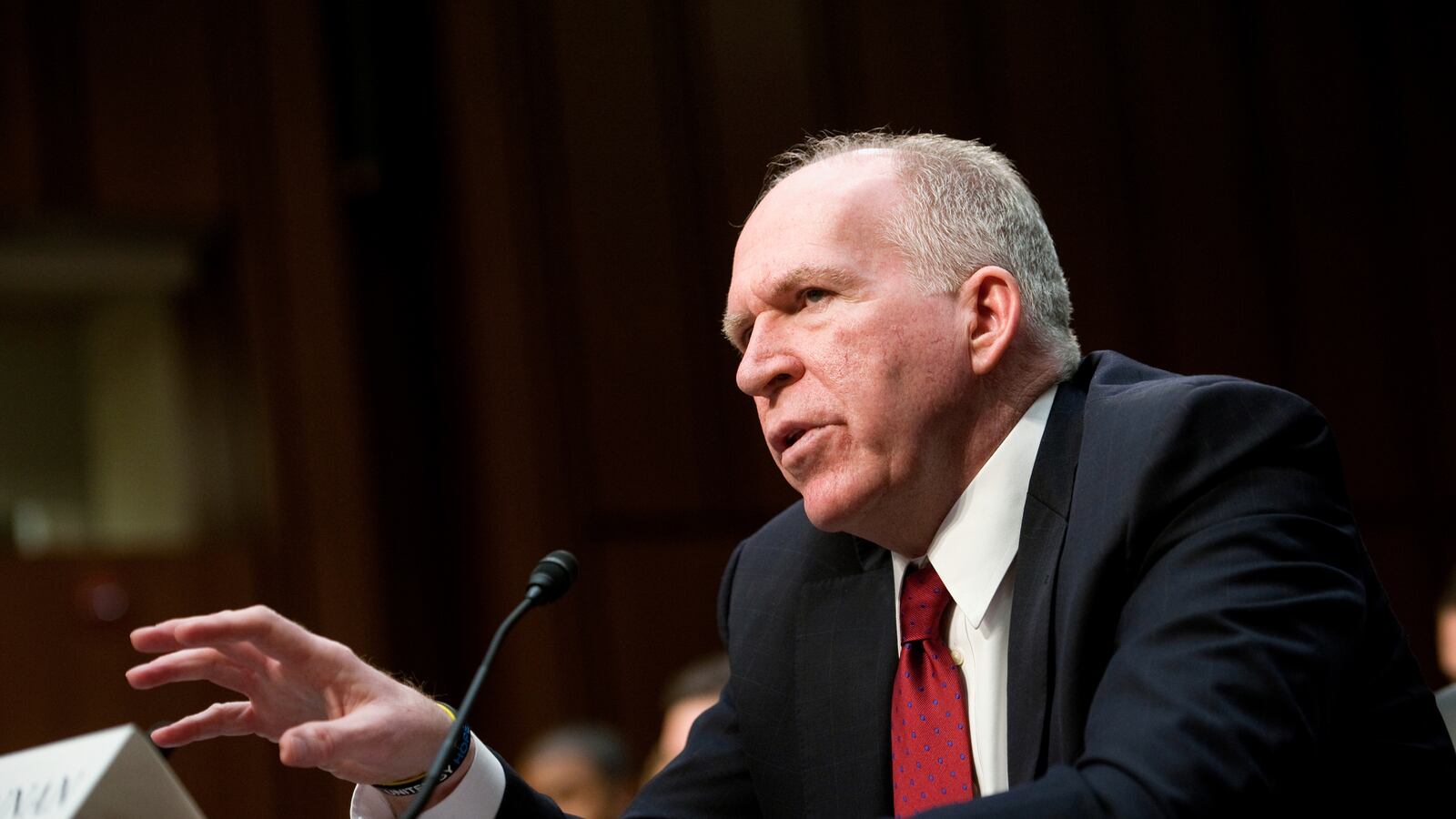

In the run-up to yesterday’s Senate confirmation hearings for would-be CIA director John Brennan, everyone was waiting for an epic clash over the morality of drones. Brennan, having spent the past four years as Obama’s chief counterterrorism adviser, has been at the center of the administration’s targeted killing program—which seemed to make his nomination the perfect moment for a showdown between Congress and the White House on the subject. The potential for drama was only heightened with the recent leak of a white paper outlining the Obama administration’s legal rationale for targeting American citizens.

And the hearing did get off to an unruly start. Code Pink protesters repeatedly disrupted the proceedings until they were ejected from the room. One woman held up a placard that read “drones fly, children die,” while others called Brennan an “assassin.” There were also plenty of heated exchanges between Brennan and the senators: Democrats bored into him over the drone program’s lack of transparency, and Republicans hammered him with questions about classified leaks and his alleged involvement in the Bush administration’s harsh interrogation program.

Yet despite the testy exchanges and the theatrical protests, it’s worth noting that not a single senator said he or she opposed targeted killings. It was perhaps a recognition that drones are here to stay—a permanent part of America’s hi-tech 21st-century arsenal. Indeed, instead of a dramatic moral showdown, the hearing showcased evidence that Congress and the Obama administration could be moving toward pragmatic compromises which would impose more accountability on, but not eliminate, the drone program.

These compromises came in the form of two concrete proposals. Dianne Feinstein, who chairs the Senate Intelligence Committee, revealed that the panel was reviewing proposals to establish a special court that would assess the government’s evidence against American citizens it wants to target—an idea that may give comfort to critics who say the current approach deprives Americans of their right to due process under the Fifth Amendment. Feinstein was vague about how a special court overseeing targeted killings might work. But she suggested it could be an “analogue” to the secret judicial panel that grants the government surveillance authority in counterterrorism and espionage cases.

To be sure, the prospect of federal judges second-guessing the targeting judgments of military and intelligence officials will without a doubt face stiff opposition from the Pentagon and the CIA. Still, while Brennan reacted cautiously to the idea, he also said it was “certainly worthy of discussion.”

To get a sense for why Feinstein is so eager to impose this kind of accountability, it helps to understand just how ad-hoc the administration’s current process can be. Consider the lethal targeting of Anwar al Awlaki, the American citizen and al Qaeda member who was killed in a CIA drone strike in Yemen in September 2011. Awlaki was actually placed on the kill list before the Justice Department had finished its opinion, though Obama’s lawyers had already weighed in orally. As for due process, it was far more informal than anything Feinstein envisions. One example: before State Department legal adviser Harold Koh was willing to give his blessing to the deliberate killing of an American, even one who had joined an enemy force, he wanted to scrutinize the intelligence himself. So in March 2010, he holed up in a secure room in the State Department and pored over hundreds of pages of classified reports detailing Awlaki’s alleged involvement in terror plots. Koh had set his own standard to justify the targeted killing of a U.S. citizen: he felt that Awlaki would have to be shown to be “evil,” with iron-clad intelligence to prove it. After absorbing the chilling intel, which included multiple bombing plots and elaborate plans to attack Americans with ricin and cyanide, Koh concluded that Awlaki was not just evil; he was “satanic.” (I originally wrote about this in my book Kill or Capture.)

Another proposal that came up at the hearing would impose a measure of accountability on the back end. Brennan was asked whether he favored the establishment of an independent, or at least more objective, panel that could conduct after-action inquiries in the wake of individual strikes and assess the effectiveness of the program. Absolutely, responded Brennan, who has himself championed the idea within the administration, arguing that there is an implicit conflict of interest when those who pull the trigger are then in the position of judging their own work.

For those—and there are many—who are distrustful of the government’s assertion that civilian casualties under the program have been negligible, this could be a valuable check. And it’s an idea that seems to be gaining traction outside and inside the administration. In his latest column, The New York Times’s David Brooks called for the appointment of an independent board made up of retired military and intelligence officers who could keep tabs on the effectiveness of the program. Meanwhile, two sources tell The Daily Beast that the co-chairs of the president’s Intelligence Advisory Board—David Boren (a former chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee) and Chuck Hagel (Obama’s nominee for secretary of Defense)—have suggested that the National Counterterrorism Center play such a role.