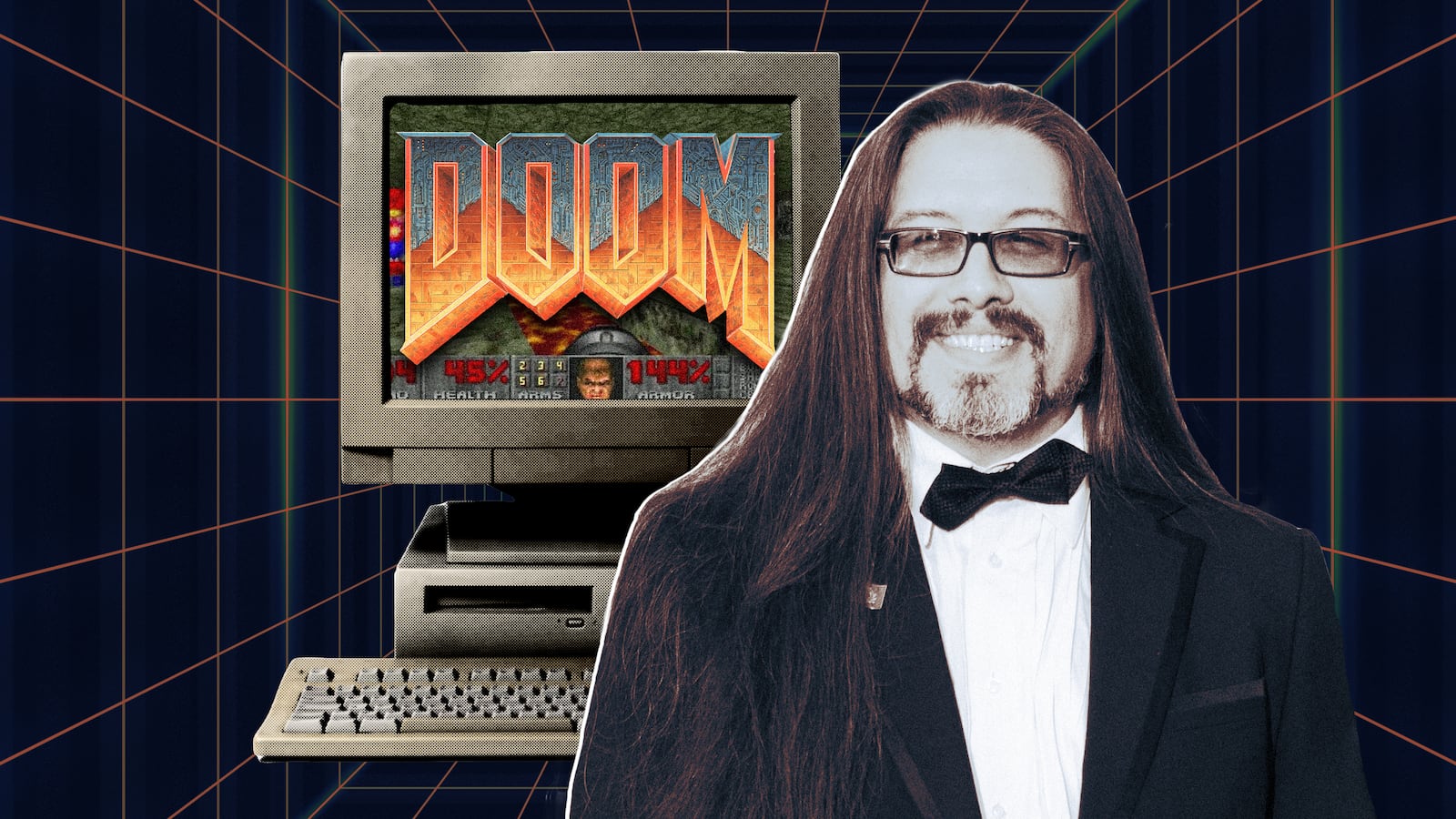

John Romero was the first rock star of video games: a long-haired, high-tech artist who repeatedly revolutionized the industry with his innovative triumphs, including the Nazi-slaughtering Wolfenstein 3D and medieval-themed Quake. It was 1993’s Doom, however, that forever cemented his legacy as a PC gaming legend. With Doom, Romero ushered in the age of first-person shooters (FPS), defined by fast, brutal violence and chaotic, kill-or-be-killed multiplayer deathmatches. Doom transformed interactive entertainment forever, and even today, it remains one of the most popular—and significant—titles in gaming history, spawning not only sequels and remakes but even a (not-very-good) 2005 movie starring Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson.

With his gung-ho enthusiasm, brash attitude, and fondness for heavy metal, Romero looked and acted the rebel part. He recounts his rags-to-riches saga in Doom Guy: Life in First Person, a candid autobiography (July 18) that traces his path from crime-plagued poverty to the forefront of indie (and then mainstream) gaming celebrity. His rise, though, was followed by a fall: After breaking free from id Software—the company he co-founded—due to a contentious and rumor-plagued fallout with lead programmer John Carmack, Romero struck out on his own, only to stumble with his subsequent Ion Storm studio and its heavily hyped FPS, Daikatana.

The infamous ad for that game claimed that “John Romero’s About To Make You His Bitch....Suck It Down,” and it did not go over well with the public, who viewed it as proof that Romero’s head had grown too big for his famously large mane. Still, no amount of professional or personal embarrassment could diminish Romero’s impact on the medium. His contributions include not only creating FPS and deathmatches, but also inventing the concept of speedruns (seeing how fast you can complete a game); spearheading online multiplayer and the use of “game engines” (foundational programming tools used to build games); and encouraging modding, which allowed players devise their own custom levels and features for mass-market games. Few boast a resume with so many trailblazing accomplishments.

Now 55, Romero remains as passionate about games as ever. In recent years, he’s returned to the hellish hit that made his career, producing a new level for Doom II whose proceeds went to support the Ukrainian Red Cross and the UN Central Emergency Response Fund in the ongoing war. Doom Guy suggests that even more fresh Romero material is on the way. But its real hook is a straight-talking insider account of an inspiring self-made career marked by amazing highs and difficult lows.

In advance of his autobiography’s debut, Romero spoke with The Daily Beast about Doom’s longevity, his fondness for metal, his current relationship with Carmack, and his upcoming return to the genre he pioneered.

The conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Decades later, do people still demand that you “make them your bitch?”

[Laughs] It’s funny—that marketing campaign still reverberates through time. Thankfully, no they don’t! They’ve gotten past that.

I’m sorry. I had to say it.

You gotta say it! But if people say anything about it, I just laugh, because it’s ridiculous.

Do you feel like that ad contributed to your reputation as cocky?

Oh, yeah. It totally fed into that, and it was a terrible idea, because that’s not anything I would ever say to anybody [laughs]. It’s trash-talk, but not the kind of trash-talk that I normally do when I deathmatch. It was totally out of character.

DOOM Creator John Romero challenged by gamers on DOOM during the Milan Games Week 2016 on Oct. 14, 2016 in Milan, Italy.

Rosdiana Ciaravolo/Getty ImagesYou’re responsible for many gaming firsts, all of which are touched upon in Doom Guy. What do you consider your greatest—or most influential—professional achievement?

It’s hard to pick. If you look at all that stuff, it points toward Doom, because Doom had all of it. Doom was first in a lot of things. Doom was [id Software’s] fifth first-person shooter, but it was the one that cemented the design of the first-person shooter. So I would say Doom, because it’s shooters, modding, deathmatch, speedrunning, multiplayer—you name it. So much is in there.

Were you surprised at the time that Doom’s interconnected element—letting us play against multiple people in the same world—instantly became such a big, core facet of the game?

When I was envisioning what the game would look like, even before we had [networking] in it, from the third-person, seeing two other people fighting in the game, I was just like, this is going to be the coolest thing ever. Sure, I’d love to be the guy shooting rockets at the other person. But to see that happening between two other people—there’s a world of this happening! I just knew, at that point, this is going to be the coolest game that this planet has seen.

I always say crazy, big stuff like that [laughs]. But I knew then that multiplayer gaming—that was it, forever. As soon as you can play against another person, not an AI, it’s esports, really. Everything happened from there.

That’s the way it felt at the time, too.

The psychological games you play with the other person when they’re really good, and you’re really good … there are some bugs in the game that people know, and that you use against each other, and the experts know that you’re trying to use them against them. It’s all this crazy reverse-psychology and Inception-like crazy stuff. It’s amazing.

What do you make of Doom’s longevity, not just as a property, but in its original form too?

It’s unbelievable. I’m super-grateful. The community around Doom has been exceptional. Just this year, the biggest and most amazing mod was released, called “My House,” that’s 70MB, and there’s just no [other] mod that’s 70MB! It’s so good. Thirty years later, we’re seeing some of the best stuff.

And even in Quake, 30 years later, we’re seeing speedrun records dropping that have been held for decades. The skill ceiling in Quake is still unknowable to people, because of the way that it works and calculates angular velocity and movement, so people are still figuring out new techniques. Like, bunny hopping in games is a thing, but bunny hopping in the first Quake is different than every other game, and that’s what’s dropping all these speedrun records. And it’s this year—this is new! It’s unbelievable.

We’re just lucky we programmed the games to be like that. We didn’t know there was rocket-jumping [laughs]! It’s gotten so much more advanced.

Has modding been the key to keeping Doom and Quake alive and vital?

Definitely. The modding has carried [both games] forward for this entire time. If [Doom and Quake weren’t] moddable, people would not be so involved still. … When you make a new level, your level feels good—that engine, like Quake, feels really good. You feel like you could make actual Doom maps yourself. “I could have done this!” It’s not like when you make a map, it feels janky or not as good as the original. It can be absolutely as good as the original maps.

That community has held it up for so long, and they have award ceremonies every year for that stuff, still. One of the coolest new WADs [the package used for Doom mods] just came out this year, and is super impressive and is doing things that no one has ever seen the engine do…using GZDoom, but still doing conceptually really amazing things that fits in the Doom mode. The mod community has been exceptional—it’s the reason the game is still around, and why there’s a Doom 2016 and Doom Eternal.

Those reboots used modern technology, but do you feel like they maintained the original’s spirit?

Absolutely. At QuakeCon 2014, which was two years before Doom 2016 was released, people got to see a preview of it, and they were blown away by it. I didn’t know anything about it, and I saw nothing, because I didn’t go into that room where they were showing it. I was busy talking to other people. But when I heard the reaction, I thought, this is going to be so good. I’m so glad, because it had such a journey to define what Doom is today. The way Doom was back then can’t be recreated today. But what does Doom really stand for? The re-do in 2016 absolutely captured all the aspects of Doom as it felt back in the day.

Because it was such a fast, violent game back then, playing it today, it’s like a cartoon. But the new one needed to feel just like the original one did, so [the developers at id Software] spent seven years getting that thing rebooted four times, until it finally nailed the future of what Doom is. They’re not letting it go stagnant—they’re still developing it. That team has done an incredible job. They’re exploring the possibility of the IP and what it can do, in the same way that MachineGames is exploring the [possibilities of] Wolfenstein. I’m just really happy with what they’ve done.

A scene from the original DOOM video game from 1993.

id SoftwareThe one thing missing from Doom Guy is any extensive talk about your love of heavy metal, which is such an integral part of Doom. Do you still listen to metal? Who was on your stereo when you were making the game?

[Laughs] Hell yes. Still listen to it. It’s the reason why, if you’ve played or know about SIGIL [Doom’s fifth chapter, which Romero produced in 2019], Buckethead is in there. Buckethead is my age, he was born the same year, and we had mirror existences for a while—he lives in Anaheim, and he loves Disneyland, and I love Disneyland. … I really identified with him.

I love ’70s and ’80s metal. I absorbed all of it, I listened to it all the time. While Doom was being made, it was Black Sabbath, Judas Priest, a lot of Alice in Chains, and Queensrÿche—The Warning and Rage for Order. I’ll never forget, making [level] 7, listening to The Warning. I needed to feel an epic vibe while I was making that level, because it was the last big level of the game, and I wanted to hear something epic. “No Sanctuary,” “Roads to Madness”—I needed to have those epic Queensrÿche songs playing to feel what I was trying to put into that level.

That’s one of the things I do when I’m developing—I want the environment to reflect what I’m putting into whatever I’m doing.

The music is central to Doom’s spirit.

I almost wish that Wolfenstein had that. Wolfenstein was a WWII period piece, so it had the anthems from back then, which was appropriate. But I totally could have had Megadeth or Metallica [playing] while blowing through Nazis—that would have been so good!

With Doom, you name it, I listened to every one of those groups [featured in it]. I listened to so many obscure groups that nobody knew about. Crimson Glory. King Cobra’s initial demos. I was a big BulletBoys fan. Solitude Aeturnus. Psychotic Waltz. Dark Star. I was into everything. Metal!

We have to promote it whenever we can.

It’s my aesthetic. Doom Guy 2, I’ll talk about metal and how I live it.

Daikatana was a high-profile letdown, but the game was fun, and it had a great hook. Do you think it still has potential, either via further modding or a sequel/reboot à la Doom and Wolfenstein?

That game—thank you for liking it. I actually have a lot of Daikatana fans. They email me all the time, saying “I thought the game was great!” But any game that you make could do more, if it was almost there. Daikatana launched with a lot of issues. When we hit our release date, it was [version] number 18, and there were still bugs in it. But it’s amazing that the community has been so busy fixing it. I gave them the source code 15 years ago, and they’ve been fixing everything—removing psychics if you don’t want them in the story, and just making it the core shooter experience without the story part. It’s amazing that they’ve made it the game that’s the state I wish it was in [when it launched].

People ask me about remastering or making the sequel, and I don’t know if I want to tell that story again. There are so many other stories and so many other games to make that I don’t feel like revisiting that world. It’s a moment in time. It was difficult to make, and we didn’t have day-one patches back then. Anyone who’s trying to do anything will fail at one point—it happens. But you learn from your mistakes, and then you move on to make another game, and you hopefully do better.

There was talk of a Daikatana 2 at some point.

Back at that time, I was starting to do a Daikatana 2 with Human Head Studios, and then the publisher decided, let’s not do that right now. I said okay, and they went off and did Rune. They were using the early Unreal Engine at that time. But it’s funny, because there’s a bunch of characters, so many enemies, so many weapons, time periods, music—all of that stuff. I think of the idea of that adventure, and going back through different time periods and being limited by nothing—you come through a time period with nothing and you have to find weapons—I love stories that have to do with time travel, flat-out. It doesn’t matter if it’s a movie or a game. So a time travel game, I’m still definitely up for something like that.

Plenty has been written and said about your time with id Software and your relationship with John Carmack. Was Doom Guy partly inspired by a desire to set the record straight?

I think that’s one of the really helpful parts of the book, because the book’s not trying to set the record straight on anything that’s been published before—because everything has been published before. All I focused on is telling my story and how things really were, and people can tell from the book that John and I had an incredible working relationship together. We used to hang out and talk to each other when we weren’t coding and developing stuff, and we still talk and sometimes do Zooms together. It’s not like what people might think. But at the end of Quake, our goals were fractured—he wanted one thing, and I wanted to grow the business, and it was kind of explosive.

We both agree that we were really young, and we would have made a totally different decision nowadays. We could have gone several different ways and stayed together, but we’ve talked about that whole thing since. John’s given me his thoughts about what he would have done better, and I told him, yeah, my idea was kind of like this. But it happened! We’re at zero animosity. We did some cool stuff together, and we’re not going to ruin it with, for some reason, hate. There isn’t any. I’m really happy about what we did together. We were in our 20s!

At the end of Doom Guy, you tease a new FPS. Can you tell us anything about it, as well as about your other future plans?

SIGIL II is coming [on December 10, 2023], because it’s the 30th anniversary [of Doom] now; the last one was for the 25th. So that’s happening. I’m also working on a FPS. I have a major publisher already, and I’ve been working on it for a while. The team has been growing, and I’m using Unreal 5.

But no further details yet?

I can’t say anything else about it, because I’m not the publisher and the marketing team, and they want to hold that for the right time. But you’re shooting and blowing shit apart, and it’s first person!

You say some unkind things about Myst in Doom Guy. Even today, Myst still sucks, right?

[Laughs] You know, the funny thing about Myst was, when you talk about the range of games that people play, back then, our focus was hardcore, fast, 3D is the future. That’s where we were going. When we saw Myst, it was like, what is this? We were not thinking, that’s for my mom, who actually would play that game—which is probably [true of] a ton of people who are into casual games! But there weren’t that many back then.

It was the opposite of Doom, and that’s where we were at, and that’s how we needed to think in order to keep doing what we were doing. But [Myst] was a massive game. It sold CD-ROM drives like crazy, and SVGA cards—we couldn’t do resolution that high at the frame rate we needed. That game had no frame rate, but it looked really good! It was for other people who were not into action and the kind of thing we were doing. But that’s why, in 1993, while we were making Doom, that game came out and knocked Wolfenstein off the Usenet top 100 until Doom came out.

It was a huge game for a lot of people.

It was, but…

It wasn’t for me, but it was for millions of other people [laughs].

To each their own.

It was a legendary game—I have to give it props. I did a talk with [Myst co-creator] Rand Miller. It was a 20-year [anniversary] thing, at New York University, and it was great. I got to talk to a lot of people about the two games, and what the legacies were for both.

The opposite extremes of ’90s gaming.

[Laughs] But the two biggest games of the year!