Note: This article was originally published on June 6, 2010.

In the annals of blown calls, it ranks somewhere between the publishers who turned down the first Harry Potter book and baseball umpire Jim Joyce’s instantly infamous perfect-game flub last week. It was the spring of 1985, and the board of Apple Computer decided it no longer needed the services of one Steven P. Jobs.

Fate had a doozy in store for the men—and they were all men—who dumped the famously combative Jobs. The upstart they fired eclipsed them by many magnitudes, as emphasized two weeks ago when Apple passed Microsoft to become the most valuable technology company in the world.

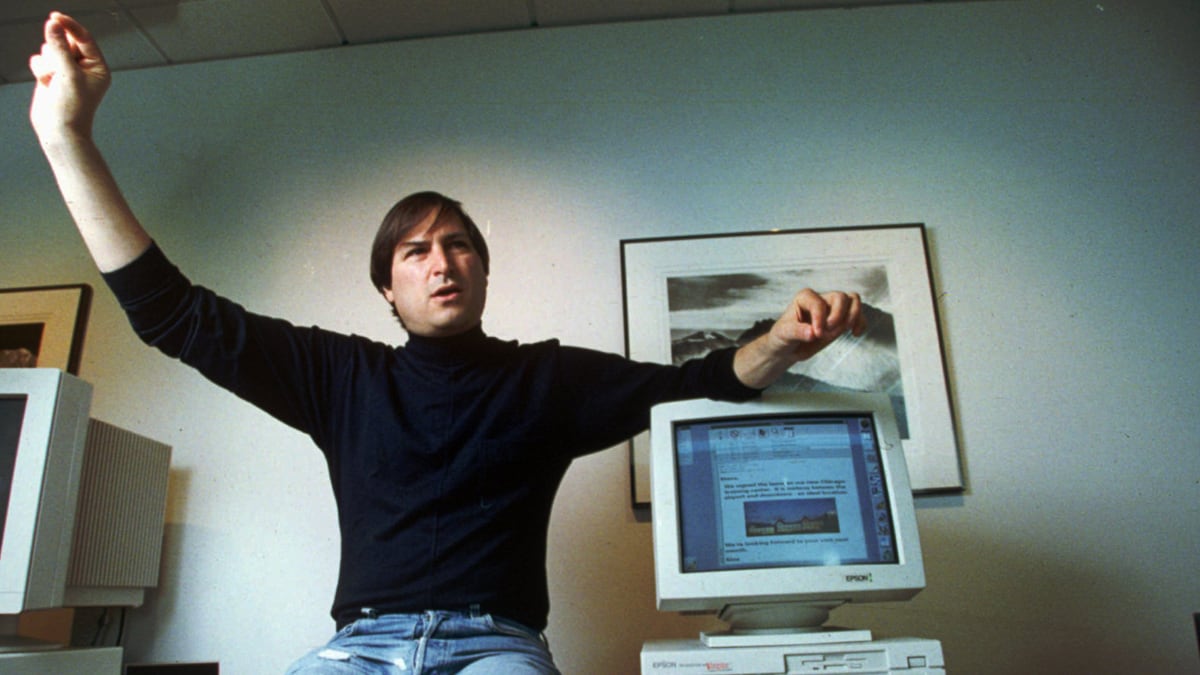

The key antagonist in the tech world’s biggest soap opera of a quarter-century ago: John Sculley, the Pepsi executive whom Apple’s board brought in as CEO to oversee Jobs and grow the company—similar to Eric Schmidt’s role with Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin—in 1983. A marketing whiz who had invented the “Pepsi Challenge” campaign, Sculley wrestled with low Macintosh sales and a need to bring some order to the creative chaos Jobs had unleashed. Sculley found that he couldn’t rein in Jobs—and decided he had to go.

Today, Sculley credits Jobs for everything Apple has accomplished and still laments the way things turned out. “I haven’t spoken to Steve in 20-odd years,” Sculley tells The Daily Beast. “Even though he still doesn’t speak to me, and I expect he never will, I have tremendous admiration for him.”

Twenty-five years later, of course, canning Jobs seems like obvious folly. Restored to the helm of a floundering Apple in 1997, Jobs is now the most respected CEO on the planet—he took to the stage Monday at the exclusive Apple Worldwide Developers Conference, where he unveiled the latest iPhone to adoring fans. Products that Jobs has championed—the iPhone, iPod, and now the iPad—are remaking entire industries.

Firing Jobs may not have been the visionary move, but it was far from condemned at the time. Sculley clashed with Jobs, who oversaw the division that had introduced the Macintosh computer to halting sales a year earlier. So Sculley and the board removed him from his Mac role, leaving him only a ceremonial chairmanship.

Today, the transformative role of personal technology is widely accepted, and so is the archetype of the eccentric founder whose spark is precious. Companies like Google and Facebook have strived—and thrived—by keeping their far-seeing geniuses on board. But Apple’s board didn’t have those examples to work from.

Another Apple board member at the time was Peter O. Crisp, general partner at Venrock Associates, a venture-capital outfit started by members of the Rockefeller family. In an interview with The Daily Beast, Crisp recalled how undisciplined Jobs and the original Apple crew could be—enough so that they didn’t shrink at defacing the home of David Rockefeller.

Crisp describes a cocktail party Rockefeller hosted for management and bankers to celebrate Apple’s initial public offering. He says Rockefeller told him the following day that he enjoyed the party with Jobs and other top Apple managers, but added, “Next year, ask them not to put logos on the mirrors in the lavatory.” Some of the Apple faithful, it seems, had come armed with stickers of the company’s multicolored emblem.

Like Sculley, Crisp credits Jobs for Apple’s recent successes. “Steve came back and really took the company in the directions that it’s gone in recent years with much skill,” Crisp says now. But the ouster remains a sensitive subject and Crisp—who left Apple’s board in 1996 after serving 16 years—won’t discuss it directly.

Sculley says he accepts responsibility for his role but also believes that Apple’s board should have understood that Jobs needed to be in charge. “My sense is that it probably would never have broken down between Steve and me if we had figured out different roles,” Sculley says. “Maybe he should have been the CEO and I should have been the president. It should have been worked out ahead of time, and that’s one of those things you look to a really good board to do.”

“Maybe he should have been the CEO,” says Sculley, “and I should have been the president.”

Sculley now says that one of his biggest regrets is that when he found himself pushed out of the CEO job, he didn’t try to recruit Jobs back to Apple. To Sculley, that could have helped Apple avoid years of floundering. “I wish I had gone back and gotten hold of Steve and said, ‘Hey, I want to go home. This is your company still. Let’s figure out a way for you to come back,’ ” Sculley says. “Why I didn’t think of that, I don’t know.”

Board member Arthur Rock, a venture capitalist who helped found Intel, among other outfits, dubbed Jobs and his co-founder Steve Wozniak as “very unappealing people” in the early days. “Jobs came into the office, as he does now, dressed in Levi’s, but at that time that wasn’t quite the thing to do,” Rock told a little-noticed University of California, Berkeley venture-capital oral-history project. “And I believe he had a goatee and a mustache and long hair—and he had just come back from six months in India with a guru, learning about life. I’m not sure, but it may have been a while since he had a bath.” Rock declined to comment for this story. Apple didn’t respond to a request for comment.

After ditching Jobs, Apple fought to show it could turn things around without its co-founder and driving visionary. The company’s 1985 annual report is a remarkable document, beginning with a huge proclamation on its cover: “We had to take swift action. We did. And it’s working.” Inside the report, Apple comes off as defensive, offering reproductions of faux internal memos (“not actual memos” but “representative of actual management communications,” the report calls them). These pseudo-memos are shown complete with date-stamps and handwritten comments by Sculley and include another exec’s call for restructuring that included the notation “I strongly agree! Let’s discuss—John.”

In fairness, the Gospel According to Steve resonates far more clearly today. But in ’85, even high-tech enthusiasts were still trying to figure out what to do with “home computers.” (Word processing and keeping a database of kitchen recipes were popular options.) Jobs’ dreams that personal technology could leverage our brains’ power “like a bicycle for our minds”—which drove his single-minded view of what Apple’s products should be—were truly ahead of their time, and not a sufficient response to shareholders facing losses.

The board members from that era have long since parted ways with Apple, which now counts Al Gore among its directors. Meanwhile, Jobs can bask in the afterglow of all those “Apple Now Bigger Than Microsoft” articles and a fresh wave of iPhone raves. “Apple is in the catbird seat,” says Sculley. “The same principles Steve is so rigorous about now are the identical ones he was using then. Now he’s a lot wiser and a better business executive.”

“My guess,” Sculley adds, “is that Apple won’t just pass Microsoft in market capitalization, but will go way beyond it.”

Thomas E. Weber covers technology for The Daily Beast. He is a former bureau chief and columnist at The Wall Street Journal and was editor of the award-winning SmartMoney.com. Follow him on Twitter.