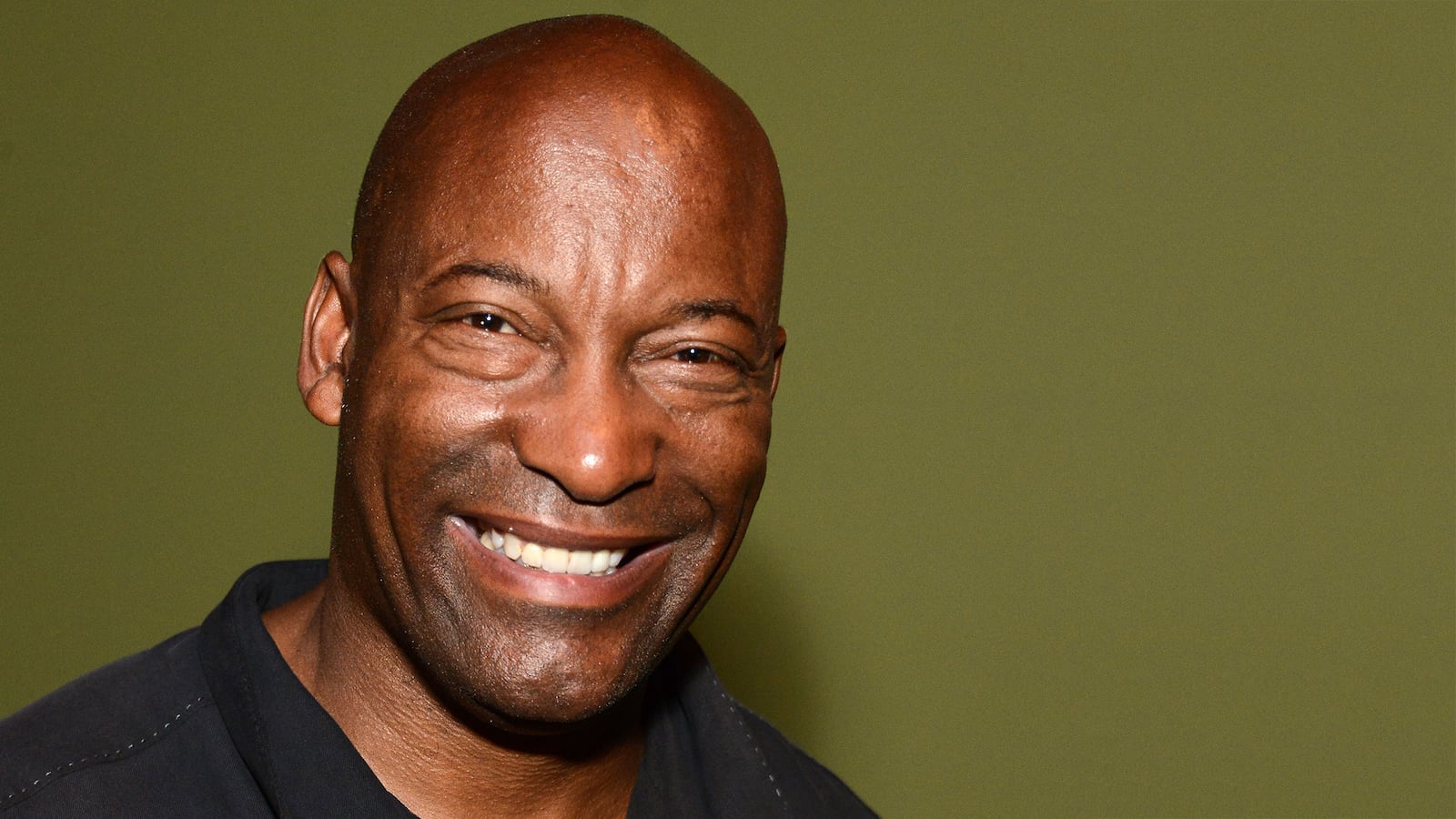

John Singleton has been telling stories in Hollywood for the better part of 30 years. The man who directed Boyz n the Hood and landed a Best Director Academy Award nomination at 23 is part of a vanguard of black filmmakers who defined the ‘90s—alongside names like Spike Lee, Matty Rich, Julie Dash and F. Gary Gray. When Singleton looks back at those early days, he doesn’t sound wistful or nostalgic, he just sees his early work as a young man figuring it out while trying to tell compelling stories as best he could.

“I look at stuff now like, ‘OK, that’s where I was in my early twenties. That’s how I was thinking in my early twenties,’” says the 51-year-old filmmaker. “I was trying to work it out and I appreciate being allowed to work it out. Now, you don’t get a chance to learn on the job. I learned on the job. I had the chance to have triumphs and mistakes and learn from those mistakes by making films. And I’m very grateful for it.”

Singleton followed Boyz n the Hood with 1993’s Poetic Justice, a film that did well at the box office and became beloved among fans. It tells the story of South Central hairdresser Justice (famously played by Janet Jackson) who withdraws into poetry after witnessing her boyfriend’s (rapper Q-Tip) senseless killing. She eventually meets postal worker Lucky (Tupac Shakur) and they form a bond. The movie received middling reviews from mainstream critics, but remains a standout in Singleton’s canon and one of his most enduring films.

“It was the first—and I guess only—time I’ve had a female protagonist as the lead character in a picture,” he says. “I wanted to do something very different with my second movie. I was young and just starting my career and had to make a mark. It was an interesting time for me as a filmmaker and storyteller.”

“There’s nothing I could’ve done after Boyz that would’ve satisfied [critics],” Singleton adds. “I was trying to get another movie made. I knew that I had to have talent involved—no matter what the movie was—that would commercially be a hit film. I met Janet Jackson—I knew her from before as a kid—and I was like, ‘Bam, I’m writing a movie for you.’ I gave her the script and she said, ‘Interesting.’ It was a whim, and we wound up doing the movie. It was like I was surfing a big wave.”

That “big wave” included both Boyz and Poetic Justice alongside 1995’s topical college fable Higher Learning and 1997’s period piece Rosewood. Singleton was carving a space for his voice and voices like his. But he was still very young—and that’s the “learning on the job” that came along with his major Hollywood filmmaking.

“I directed all three of those [first] pictures before I was 26 years old. So basically, my graduate school was doing feature films. When I was directing Boyz I was supposed to be going to graduate school to study film. I became a feature film director instead of going to grad school.”

His early-twenties success made him a fixture among black influencers of the time and his age meant that he was connected to a wave of young black artists emerging out of hip-hop. Singleton worked with a litany of rappers like 2Pac and Ice Cube (alongside Tone Loc, Busta Rhymes, and the aforementioned Q-Tip.) When he thinks about that time now, he sees the way hip-hop emboldened his generation. And he recognizes that what was happening then was indicative of then, and not something that can be contrasted with what came before or after.

“You can’t compare time periods,” he believes. “In my time, I couldn’t compare what was happening in that time to what had happened in the ‘70s with filmmakers of color, y’know, in the Blaxploitation era, and Gordon Parks and Melvin [Van Peebles] and stuff. It was just different times for different people. The great thing for me was I lived in the time when hip-hop was coming to prominence. You had a burgeoning youth movement via hip-hop going into the mainstream. We worked hand in hand to see that become pop culture. What was a subculture when we were coming up is now pop culture. They used to just relegate us as a subset of pop culture and now it is pop culture.”

And as for working with so many musical artists, Singleton’s connection with them was as friends, first and foremost. He surrounded himself with the people he genuinely liked.

“Outside of the art and filmmaking and musicians, I just admired them as people, as folks I was hanging with,” he says. “In my twenties, that’s the kind of folks I was hanging out with—I was hanging out with a lot of musicians. At the time, the thing was just to go get the hottest person of the moment. Well I never got the hottest person of the moment and put them in a film. I didn’t do that. Even Pac—he had done Juice, but Juice wasn’t’ even out when I asked him to do the film. Cube didn’t want Poetic Justice. And I knew I had to get a real dude that guys would like and girls would like opposite Janet. He wasn’t really 2Pac until after [2Pac’s breakthrough single] ‘I Get Around’ came out and the second album came out—that single came out that summer and then he became 2Pac. ‘93 was 2Pac’s year.”

Singleton has shared that he advised 2Pac to forego his career in hip-hop to focus on movies. It’s something that people laugh about now, but at the time, Singleton saw more in Pac as an actor. And he wasn’t altogether silly for saying so—despite his own chagrin when telling the story today.

“I’m the stupidest person in the world to be telling Pac [that],” he says with a chuckle. “When we were working initially, he wasn’t that good a rapper. I was like, ‘You a’ight, but you a better actor.’ He was like, ‘Fuck you, man. Hip-hop is my voice.’ Hip-hop, being a rapper—that’s like being a gunslinger, that’s your manhood. Can’t nobody take that from you. If you can spit 16 bars and take somebody down that’s like having a multiple weapon. I’m telling him, ‘That’s not your weapon—your weapon is the fact that you’re going to be a major star.’ He couldn’t see it. I’m stupid for saying it but also, he couldn’t see it. He couldn’t see how one thing could begat the other.”

And the Janet Jackson HIV test rumor/joke that emerged as Poetic Justice was hitting theaters remains something he believes got blown out of proportion.

“That was a joke!” Singleton declares with a hint of exasperation. “Me and Pac didn’t know Janet was married so we both were flirting with her and stuff. We’re on the set joking, with Janet there and the whole cast, and I was like, ‘I don’t know if I want you kissing my actresses—I don’t know where your lips have been. We gonna do this love scene with y’all, we’re gonna have to get you a double. He was like, ‘Fuck doing that, [only] if we’re really fucking!’ We’re gonna have to get you an AIDS test for you to kiss my actress! And it became a joke. And then a joke turned into some publicity and he was the only one that was left out of the circle. He knew, but he went along with it. They were in on the joke. It was just the salt and sugar of us messing around on the set.”

Singleton has been vocal in criticizing Hollywood’s marginalizing of black directors, writers and voices, in general. While speaking to students at the Loyola Marymount University School of Film and Television back in 2014, Singleton said, “They ain’t letting the black people tell the stories. They want black people to be what they want them to be as opposed to what they are. The black films now—so-called black films now—they’re great, but they’re just product. They’re not moving the bar forward creatively.”

He reiterates a lot of that now (“They want to water us down, water [the stories] down, make the stories neutral and not potent”) but he also acknowledges that things are changing—and exactly why they are changing. “The audience won’t allow it anymore—other people telling our black stories. That’s old. You need someone, a conscious African-American, to tell certain stories. Not a puppet that’s going to do whatever.”

He’d also been vocal in his dismissals of some of the popular black rom-coms of the late 1990s/early 2000s. Back when Singleton was promoting his 2001 film Baby Boy, he believed that mainstream black films were settling, but today he realizes that it’s not about “messaging” people to death.

“Not every movie has to try to say something. Not every movie has to be an ‘important’ movie—sometimes its just pure entertainment. I think the best of those pictures was The Best Man. It had a cultural weight to it and it was cool.”

As John Singleton has grown as a filmmaker, helming action hits like 2 Fast 2 Furious and Four Brothers, and as a producer (Hustle and Flow, Black Snake Moan), he’s made a significant mark on the landscapes of film and television. Decades after Boyz n the Hood and Poetic Justice, his FX hit Snowfall is set to enter its third season—an ambitious series about how crack affected Los Angeles in the 1980s. Singleton, along with Lee and many others, has done great work on TV in recent years, but he’s not a person who believes television has usurped cinema as far as telling uniquely individual stories. John Singleton believes the fight is going to be there—no matter the platform. And he’s more than willing to continue the battle for black voices.

“It’s still very hard to get a film or a TV show on the air,” Singleton says. “It’s very, very difficult to get any type of pure vision out anywhere. But we’re trying. We’re still trying.”

Poetic Justice and Higher Learning will be released to Blu-ray on February 5.