It was a throwaway line at the end of a speech Jamie Dimon gave at an investor conference hosted by Goldman Sachs.

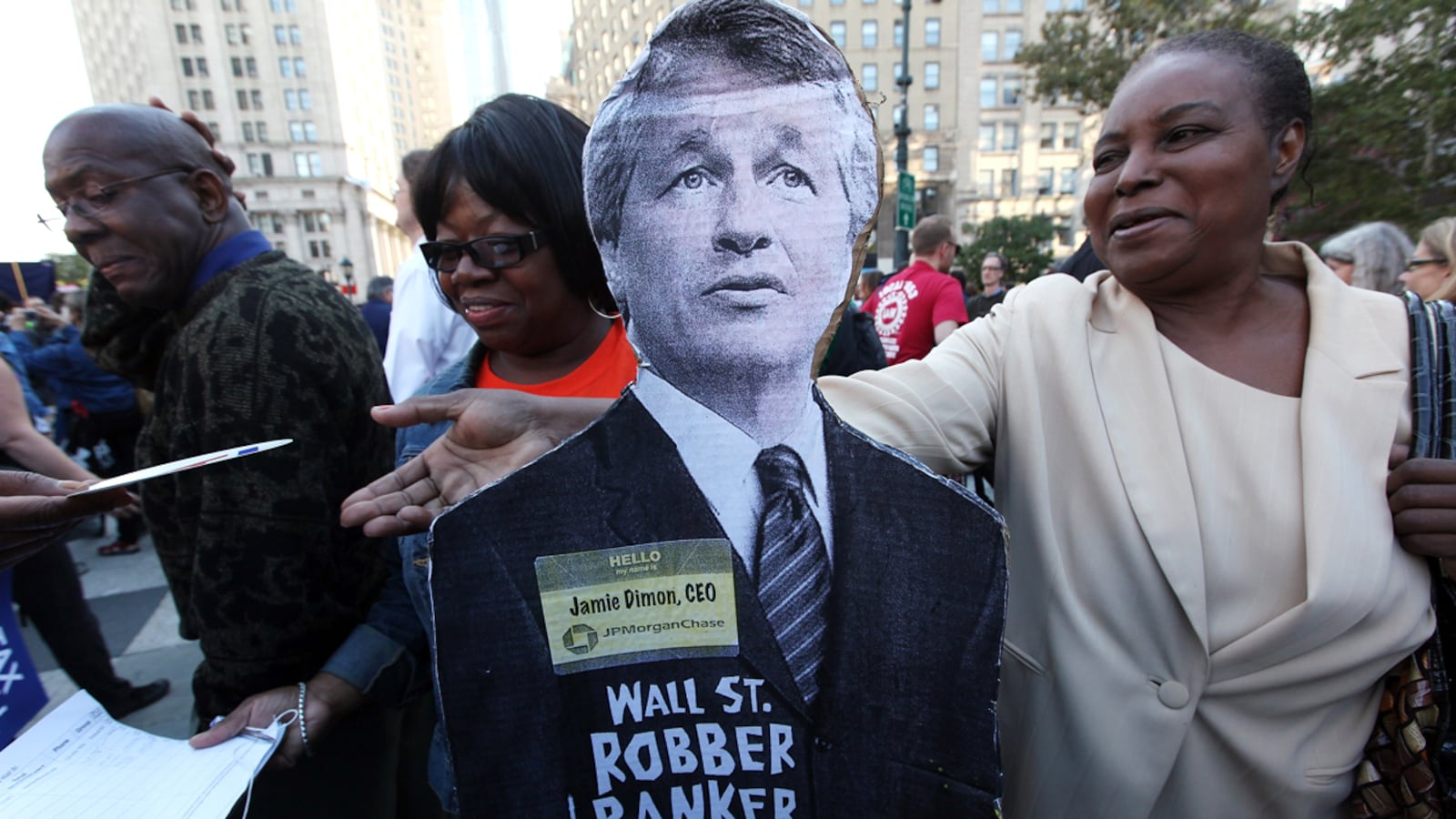

A more diplomatic chief, or at least a more cautious one, would have ducked when someone in the audience asked Dimon, the CEO of JPMorgan Chase, for his opinion on populist anger aimed at the big bank. But then these days Dimon seems to relish playing the role of hero to his Wall Street compadres—like in June, when he publicly confronted Ben Bernanke after a speech, accusing the Fed chairman and his fellow policymakers of overreacting to the 2008 subprime collapse.

At the Goldman Sachs event on Wednesday, he defended himself and his fellow poobahs with an answer that was as tone-deaf as it was brain-dead, "Acting like everyone who's been successful is bad and that everyone who is rich is bad,” he said. “I just don't get it."

Actually, the populist animus has been aimed almost exclusively at the country’s biggest banks and at others in the financial sector, not the rich in general. And it’s not success that has been the target of the Occupy Wall Streeters and others but instead the behavior of JPMorgan and the other big banks—their behavior and also their failings.

Through reckless behavior, big banks helped bring the global economy to its knees in 2008, and yet those in charge have suffered no reprisals, financial or otherwise, for their sins—another major source of resentment.

JPMorgan offers a huge case in point. The bank played a central role in the subprime disaster that caused so much misery for so many. Through its subprime arm, Chase Home Finance, the bank fed the subprime machine by originating billions of dollars of subprime home loans a year—$12 billion just in 2006, the year the subprime-mortgage orgy reached its peak.

And the bank, through JPMorgan Mortgage Acquisitions, was a huge player on the other side of the equation as well. JPMorgan Acquisitions snapped up $18 billion in subprime loans in 2006 alone, holding on to them long enough to pay a rating agency to stamp them Triple-A before selling them in bundles to pension funds, municipalities, and others—with disastrous results.

In the two years following the subprime collapse, JPMorgan Chase took more than $50 billion in losses, mainly on bad subprime mortgages.

That happened on the watch of Dimon, who took charge of JPMorgan Chase in 2004. Also under his tenure, JPMorgan admitted to congressional investigators that it had overcharged 10,000 military families on their mortgages and foreclosed on 54 of them; paid $154 million to settle charges filed by the SEC (without denying or admitting guilt) that it duped its own clients; and paid another $211 million in fines, along with $130 million in restitution, to settle charges that it defrauded local governments in 31 states. There was also the $722 million in fines and restitution payments the bank was forced to make after JPMorgan confederates were caught paying off officials in Jefferson County, Alabama (home to Birmingham), to secure a municipal finance deal that helped lead to the largest government bankruptcy in U.S. history.

For his troubles, Dimon, chairman and CEO of JPMorgan Chase, paid himself $42 million in 2006 and $34 million in 2007. Last year, Dimon received $21 million in compensation—or 900 times more than the $23,000 a year the average Chase teller makes.

As he said it on Wednesday, Dimon apparently believes we generally resent the rich for their success. But Steve Jobs was venerated after his death, despite his billions, and Bill Gates has long ranked high in polls asking people to name the people they most admire—even as the government was accusing him of being a market-crushing monopolist and long before he started earning that kind of respect by devoting most of his time to giving away his money.

The difference is that Jobs and Gates created the companies that earned them their billions. Dimon, by contrast, is a hired gun—an employee paid to run a publicly traded company. Theoretically, shareholders have a say in his compensation, but how good a job he has done seems to bear little resemblance to his pay. Early in 2008, JPMorgan Chase was trading at $45 a share—compared with $33 a share today.

People resent as well the $25 billion in TARP bailout monies JPMorgan Chase received at the end of 2008—while those facing foreclosure have received virtually no help. There’s also the $391 billion in loans JPMorgan received from the Fed in the months after the subprime meltdown, according to a GAO study. JPMorgan and other banks paid virtually no interest on these loans (0.01 percent). But Dimon, never satisfied, has cast Bernanke and the federal government as foes of the big banks.

Dimon is not just any clueless banker popping off with a dunder-headed opinion. He sits on the board of the New York Fed, and once upon a time he was Obama’s best friend in the banking world.

On Wednesday, Dimon said he’s paid his fair share in taxes on the money he has been paid. That’s debatable given the higher tax rates the very wealthy pay in most other industrialized nations—and the much higher tax rate Dimon would have paid as a U.S. citizen until a few decades ago.

But what is clear is that Dimon seems eager for a fight. He’s taken a charge that the banks have abused the country’s trust and turned it into an attack on anyone who has been financially successful. The timing of his comment is no doubt deliberate just as the country is wrestling with the question of what is a fair share for the country’s top earners to pay in taxes—and whether they pay more than their fair share, as they and their Republican allies contend.