“Woman Passes Gas in Store, Then Pulls Knife.”

It was 2018, and as she watched her newspaper’s monitor broadcasting the site’s leading stories, Miami Herald scribe Julie K. Brown seemed to be getting her clock cleaned by a goofy crime story.

She didn’t realize the impact her work was about to make.

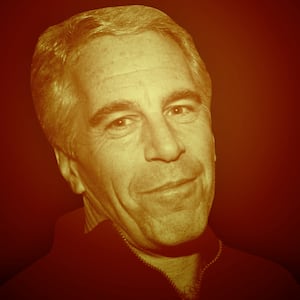

That morning, the Herald had published Brown’s three-part investigation into wealthy sex-trafficker Jeffrey Epstein’s lenient plea deal—brokered in 2008 in secret from his victims, who didn’t learn of the agreement until it was too late. It was a bombshell series that sparked a seismic shift in the public’s awareness of the case—and a collective fury that finally brought justice to Epstein’s victims before his death by suicide in 2019.

Early on, though, Brown couldn’t help but worry.

“It was getting thousands of hits,” she recalls of the fart story in her memoir Perversion of Justice: The Jeffrey Epstein Story, named after the title to her Herald series and set to be released July 20.

It was a moment of levity after her groundbreaking—and grueling—dive into how former Miami U.S. Attorney Alexander Acosta and his underlings let Epstein off the hook for abusing scores of underage girls. Within hours, reality came into focus as Brown got thousands of new followers on Twitter, and her story skyrocketed up the chart. Soon after, Manhattan federal prosecutors began probing Epstein’s activities, resulting in a July 2019 indictment that charged him with trafficking underage girls. At a press conference announcing the charges, U.S. Attorney Geoffrey Berman said “some excellent investigative journalism” had spurred them into taking action. Epstein would finally be held accountable for his decades of sex crimes.

That the series had a colossal impact is indisputable. Whether the author feels it was recognized enough by her colleagues in the journalism industry is harder to parse.

Miami Herald reporter Julie K. Brown exits federal court following a bail hearing for Jeffrey Epstein, July 15, 2019 in New York City.

Drew Angerer/GettyAccording to Brown, as the series took off after publication, her colleagues were soon standing in applause. In the coming weeks and months, she’d be flooded with calls from unrecognized numbers and unnerving knocks on her door from strangers, including one person claiming to be a pizza delivery man. Her colleague, Herald photographer Emily Michot, had a van parked outside her home. When cops eventually approached the driver, he said he was a private investigator working a case in the neighborhood.

Brown pulls back the curtain on her life behind the headlines: fears that Epstein’s operatives were watching her and Michot; emotional drives to and from interviewing survivors; battles with fellow journalists (including Conchita Sarnoff, who has written for The Daily Beast), who accused her of lifting already-reported material; and her struggles to pay the bills as a single mom of two college-age kids. (After publication of this story, Sarnoff told The Daily Beast she disputed Brown’s version of events and said, “I find it odd that” Brown “would mention my name in her book” without referring to her various reporting projects on Epstein that published before the Herald series.)

“...I was still taking biweekly pay-day loans to make ends meet,” Brown writes.

Readers looking for bombshells as earth-shattering as Brown’s original series may be left wanting more; there are no massive new revelations about Epstein or his shadowy network of enablers here. Brown does, however, share some tantalizing nuggets on the case. Among them: the previously-unreported revelation that Virginia Roberts Giuffre—who alleges Epstein kept her as a sex slave from 1999 to 2002 and sent her to other prominent men to be abused—settled her 2015 defamation suit against socialite Ghislaine Maxwell for about $5 million.

Brown also interviewed a woman from Sweden with a story to share on Epstein and his former girlfriend, Eva Andersson-Dubin, whose billionaire husband Glenn is accused in civil court records of abusing Giuffre. Since Epstein’s arrest, the couple has been under fire over their long-standing ties to Epstein, but they deny any involvement in his crimes.

The unidentified woman said that in 2003, when she was 21, she answered an ad the Dubins posted in a local newspaper for an au pair. The Dubins hired her, bought her plane tickets, and helped her apply for a tourist visa, the book says.

When she arrived in New York, the Dubins provided an apartment for her in the same Manhattan building where Epstein kept aspiring models and other young women, who told the woman that Epstein was a “friend” who “helped them.” Epstein, the woman said, would drop into the Dubins’ home frequently.

“I was disturbed by what I saw,” the woman told Brown. “I met him a few times and we would be in the kitchen of the Dubins’ home, and they had other au pairs. There were times he would grab someone. He would touch you, and he did it in front of the Dubins.”

Brown also revisits disturbing accusations against Maxwell, Epstein’s former girlfriend and alleged accomplice who is facing trial this November for allegedly grooming girls for Epstein’s scheme. One of those teenagers was Giuffre, who says Maxwell took part in the sexual abuse of her and other girls, too. (Maxwell adamantly denies this.)

Giuffre told Brown that Maxwell “could be a tyrant” with some of the girls visiting Epstein’s home and seemed to be in love with Epstein. Brown paraphrases Giuffre’s sentiments with a line noting that Epstein and Maxwell “shared a kindred hedonism.”

Giuffre isn’t the only Epstein victim who has a voice in Brown’s chronicle. Their life stories are interwoven in the book and, as reported, many of them came from impoverished and troubled homes and saw their lives further upended by the creepy financier. These survivors watched as the #MeToo era came for men like Harvey Weinstein and U.S. Gymnastics coach Larry Nassar, but, at least for a time, Epstein seemed to remain unscathed.

“Jeffrey Epstein preyed on girls who were homeless and were addicted to drugs,” Courtney Wild, a victim of Epstein who sued the feds over his plea deal, told Brown. “He didn’t victimize girls who were Olympic stars and Hollywood actresses. He victimized people he thought nobody would ever listen to, and he was right.”

As Brown continued digging into the case, more tipsters came out of the woodwork, including actor and comedian Tom Arnold. Brown says Arnold “claimed to know some of the people around Ghislaine Maxwell, who had for many years dated and been engaged to a friend of Arnold’s from Iowa, Ted Waitt.” (Maxwell’s romance with the Gateway co-founder has been widely reported.)

Arnold “said that Maxwell and Waitt had been together almost eleven years, and that Waitt probably knew her better than anyone,” Brown states.

“Arnold would continue to call or text me from time to time, hinting that he had some tidbit about Maxwell that I should look into,” Brown adds. “But none of the people associated with Maxwell would talk to me when I tried to contact them.”

There’s also newer, eyebrow-raising claims about former Epstein assistant Lesley Groff, who was granted immunity in the financier’s controversial plea deal.

During a reporting trip to the U.S. Virgin Islands, where Epstein had a private isle, Brown interviewed a couple that had worked for the sex offender, who she says told her Groff flew down shortly after Epstein’s arrest in July 2019 to remove the compound’s camera system. Brown insinuates she may have cleared out more, writing that Epstein’s “computers were moved, as well as boxes of unknown items” along with “a giant steel safe in his office.” (Groff denies this accusation and her spokeswoman told Brown she wasn’t on the island or aware of any cameras.)

The couple who made the allegation against Groff wouldn’t go on the record. “They claimed they had been required to sign nondisclosure agreements with a one-million-dollar penalty,” Brown says.

Brown shares other bits of intrigue about powerful forces working behind the scenes to shield Epstein. High-powered lawyer Ken Starr—the independent counsel who investigated President Clinton in the 1990s over the Whitewater scandal—was deployed in 2007 to convince the Department of Justice that Epstein’s alleged sex crimes weren’t federal offenses.

While assistant U.S. Attorney Marie Villafaña worked to prosecute Epstein in 2008, forces in Washington seemed to be conspiring behind her back, Brown reports.

“It was a scorched-earth defense like I had never seen before,” one unnamed prosecutor told her. “Marie broke her back trying to do the right thing, but someone was always telling her to back off. We never really knew who it was, we just thought it was very odd.”

Then, the day of Epstein’s 2008 plea hearing, which occurred in secret from the financier’s victims, a new judge was assigned to the proceeding. “One of the enduring mysteries of the Jeffrey Epstein case is how and why the judge assigned to Epstein’s criminal case, Sandra McSorley, was absent on the very day that Epstein entered his plea and was sentenced,” Brown writes, adding that McSorley was known for rejecting plea deals she viewed as too lenient. McSorley, however, told Brown she couldn’t recall why she was swapped out and added it wasn’t unusual for judges to help one another with caseloads.

More than a decade later, Brown recalled her own shock at seeing The Daily Beast break the news of Epstein’s arrest on sex trafficking charges.

“At 7:53 p.m. that night, a Saturday, I got an email from someone on the Herald’s night desk, with the Daily Beast headline: Jeffrey Epstein Arrested for Sex Trafficking of Minors,” she wrote. “I thought perhaps it was a mistake, but then my phone began ringing and didn’t stop. I called Emily, or she called me, I can’t remember. We were in shock. I called some sources who confirmed Epstein’s arrest that evening at Teterboro Airport. I honestly believe that he would never be held accountable. After eleven years, had the law finally caught up with Epstein?”

Epstein’s ability to bend institutions to his will continued once he was sentenced to jail in Palm Beach, where he enjoyed ludicrous leniency while on work release, which allowed him to visit his office 12 hours a day, six days a week. The financier demanded darkness in his cell, against the jail’s policy, barking to one corrections officer: “Guard! Why is my light on?”

He was allowed to sleep with his door open, and even emerge from “his cell with his penis on display,” Brown writes, citing the corrections officer.

That guard, Angela Watkins, told Brown that Epstein informed her he had special permission to sleep with the lights out; Epstein ordered Watkins to phone her supervisor, who she said validated the entitled inmate’s claim. “Watkins told me she filed a complaint but later learned that it was dismissed,” Brown writes. “When I asked for records of complaints filed against Epstein while in sheriff’s custody, I was told there were none.”

At some points, Brown appears defensive when it comes to the work of other journalists covering the Epstein scandal.

She accuses the New York Times of trying to extract story ideas from her, and using one tip to cover Epstein’s alleged plans to seed the world with his DNA at a “baby ranch” in New Mexico—something a Times editor disputes in his own review of her book. According to Brown, the Times wrote a feature on her and Michot just after Epstein’s last arrest in July 2019, then invited her to the building for a meeting that included reporters Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey, who exposed serial predator Harvey Weinstein. “They all began asking me questions about the series, pumping me about whether there were angles to the story that I hadn’t yet explored,” Brown writes. “I was so caught off guard that I blabbed something about Epstein belonging to a secret Billionaire Boys Club, along with some of the wealthiest people in the world, like Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos.

“It was after I opened my fat mouth that I suddenly realized what they were doing. Damn, I had just been punked by the New York Times.” She later adds of the “baby ranch” yarn: “The fact that this New York Times story likely derived from my stupid slip about the Billionaire Boys Club at that meet and greet with the Times was too painful for me to think about.” (In his review of Brown’s book, Times editor David Enrich says, “I was the editor of the article in question. Epstein’s relationships with the rich and famous struck us as an obvious reporting target. I wasn’t aware of Brown’s visit until I read about it in her book.”)

She also ponders why the Herald’s three-part series wasn’t nominated for a Pulitzer, writing, “I would never know whether efforts by some in the journalism industry to undermine my series impacted the decision-making that went into that year’s Pulitzer Prizes.”

“But it truly didn’t matter to me all that much,” Brown adds. “I was aiming for something greater than a Pulitzer: justice.”