Novelist Julie Otsuka is an Upper West Sider, with a regular spot at her neighborhood café, the Hungarian Pastry Shop. “No internet access, no music, no outlets, and the coffee refills are endless and free. I have a favorite table in the back, which is where I wrote both my books,” she says.

But the material for Otsuka’s first two novels is rooted in the West Coast. She was born in Palo Alto, California, and moved to Palos Verdes when she was nine. Her father was an electronic engineer in the aerospace industry; her mother worked as a lab technician in a hospital before having Julie and her two younger brothers.

Otsuka came east to study art at Yale, and some years later ended up in the MFA program at Columbia, where she began writing her first novel. When the Emperor Was Divine, published in 2002, captures the experience of a Berkeley family evacuated from the West Coast to a Japanese internment camp in 1942 with breathtaking restraint. It draws from family history. Her grandfather was arrested as a suspected Japanese spy the day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and Otsuka’s mother, uncle, and grandmother spent three years in an internment camp in Topaz, Utah.

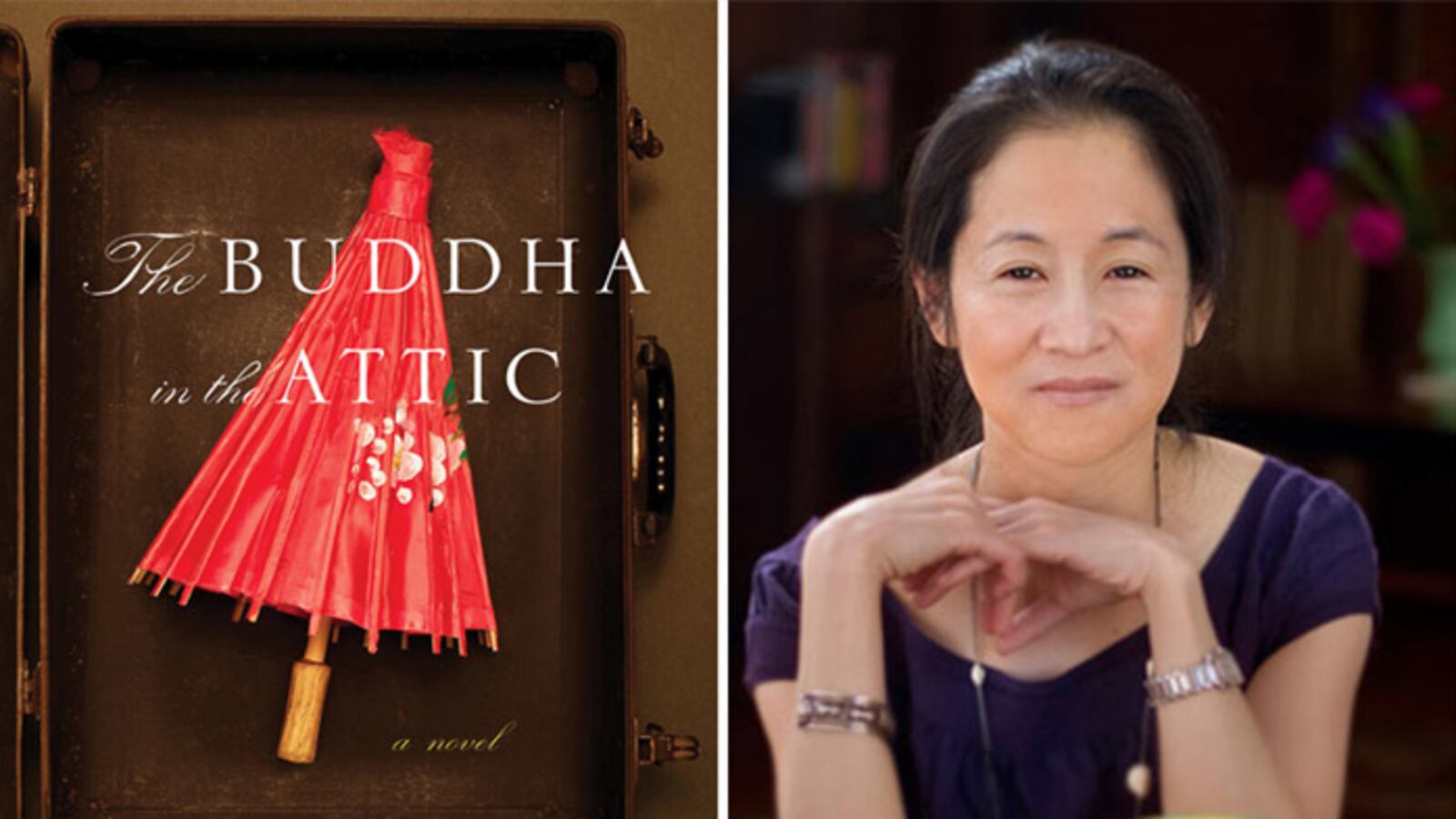

Her exquisitely crafted and resonant new novel is much less autobiographical, she says. The Buddha in the Attic follows a group of Japanese “picture brides” who sail to San Francisco in 1919 to marry men they only know through exchanging photographs. “There were no picture brides in my family, but it’s a very common first generation story. It’s how thousands of Japanese women came to this country before Asians were excluded altogether in 1924.”

This second novel, she says, entailed “tons of research.”

“I read a lot of oral histories and history books, and old newspapers. I had to learn about two worlds: the old Japan from which the picture brides came, and the America of the 1920s and 1930s which they immigrated to. I kept many notebooks filled with detailed notes about everything.”

Many of the picture brides end up doing agricultural work. “I made these crazy crop charts, showing when things ripened, and where, geographically, certain crops were grown. Also, as a child I spent some time in Oakdale (Central Valley, east of Modesto), where our neighbors’ grandparents had an almond ranch. As a kid, we’d go out there in the summer, it was great fun: lizards, frogs, snakes, irrigation ditches, bugs…”

Otsuka says she struggled for months to find the right voice to tell the story. “I had run across so many interesting stories during my research—stories of women whose husbands had sent photographs of themselves taken 20 years earlier, of women who had sailed to America expecting to live lives of leisure only to find themselves working as field hands and laundresses within days of their arrival, of women who had run away from their husbands and drifted into lives of prostitution, of women who had always wanted to come to America and were willing to marry a man, any man, to get there—that I wanted to tell them all.

“One day, while reading over my notes for the book, I found, buried in the middle of a paragraph several pages in, a sentence I had written months earlier: ‘On the boat we were mostly virgins.’ I knew at once that this would be the first line of my novel. There would be no main character. I would tell the story from the point of view of a group of young picture brides who sail together from Japan to America.”

Over time, many Japanese immigrants were so effective as farmers that they encountered a backlash in some communities. “The Japanese were extremely successful farmers,” says Otsuka. “They came from a very small island, remember, where you had to make use of every inch of space, and they knew how to make things grow. So when they arrived in California and saw this vast expanse of unplanted land, it was like catching a glimpse of paradise. They basically took wasteland that no one else would touch—rocky soil, hardpan, swamps, desert land—and turned it into fertile farmland. And their produce was better than anyone else’s, and their success was much envied.”

The Buddha in the AtticBy Julie Otsuka144 pages. Knopf. $22.

How did this envy influence the looting and violence toward the Japanese-American communities after Pearl Harbor, as portrayed in the novel? “If they’d stayed in their place as gardeners and maids, maybe they wouldn’t have been so resented. Also, their farmland, which they’d made profitable, was coveted. When they left, it was the middle of harvest time, and many of them never did get to see the profits of that last harvest—they had to turn over their farms to somebody else. They walked away from it all. Basically bankrupted themselves in the name of ‘national security.’ It was an economic boon for the white farmers who got to take over the highly productive farmland that had been cultivated by the Japanese.”

The Japanese were forced to evacuate in 1942 by Executive Order 9066, which Otsuka describes unflinchingly in the section of the novel called “Last Day.” It brings to mind Dorothea Lange’s photographs of the evacuation of Japanese Americans from the West Coast and of the internment camps surrounded by barbed wire. “I know her photos quite well. There’s a Dorothea Lange photo that we found in the National Archives of my grandmother, mother and uncle, shortly after their arrival at the Tanforan assembly center in the spring of 1942.

“Because of my background in the visual arts, I’m very interested (obsessed, actually) with detail, what things look like, so I like looking at photographs, drawings, paintings, anything that is a source of visual detail. I often have to see a scene in my head before I can begin to describe it on the page. Sometimes I feel like my mind’s a camera.”

Otsuka draws her title from a haunting visual image, an object left behind by one of the departing Japanese: “Haruko left a tiny laughing brass Buddha up high, in a corner of the attic, where he is still laughing to this day.”

And what is she working on now, sitting in her usual spot at the Hungarian Pastry Shop? “I think the next book will be set in contemporary New York City and not have anything to do with Japanese Americans at all. It’s still very early days, and I know it sounds odd, but something about swimming and dementia.”