The Department of Justice, led by Attorney General Merrick Garland, is righteously fighting back against Trump-appointed jurist Judge Aileen Cannon’s attempted meddling in an active federal criminal investigation.

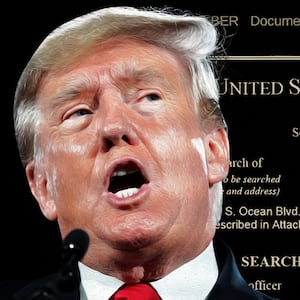

DOJ’s late-night 38-page filing with attachments—including a photo of Top Secret cover sheets recovered during the execution of the search warrant—methodically cut the legs out from under the Trump legal team’s arguments. It also exposes the lack of any sound legal basis for Judge Cannon’s potentially ruling in favor of Trump.

On Saturday, Judge Cannon stated her “preliminary intent” was to grant former President Donald Trump’s motion seeking appointment of a special master to review the documents recovered by the FBI and DOJ from the search warrant executed at Trump’s residence at Mar-A-Lago in Palm Beach, Florida.

Special masters are used in federal courts to assist judges in matters involving some “exceptional condition,” or “complex accounting or computation of damages,” or where a “district judge or magistrate judge of the district” is not available to address the issue. Typically, lawyers or ex-judges with experience in the particular subject matter are appointed, but there is no requirement that the special master be a lawyer. The idea is to increase efficiency and effectiveness by having an expert in the area take a deep dive into the complexities of an issue rather than having a judge do it.

However, putting aside the fact that Judge Cannon signaled her intent without bothering to first hear from the DOJ, she has no business trying to oversee a federal criminal investigation.

For the most part, judges oversee cases—not investigations. Courts do have oversight over grand jury investigations, but that oversight is usually done by the chief judge in the court where the grand jury sits.

Indeed, a grand jury previously issued a subpoena that resulted in some 15 boxes of documents being retrieved from Mar-A-Lago, and later review revealed that the boxes contained classified information. But Judge Cannon has nothing to do with that grand jury which presumably is investigating issues arising from Trump refusing to return government documents—including highly sensitive classified documents and documents relating to national security.

Special masters are authorized by a civil (not criminal) rule of procedure, and thus are primarily used only in civil cases. While some criminal cases have used them, those cases typically involve search warrants executed upon legal offices.

For example, the DOJ asked for a special master to be appointed to review documents recovered in the search of Trump lawyer Rudy Giuliani’s law offices, to protect documents that might fall within the attorney-client privilege. Trump is not a lawyer, of course, and Mar-A-Lago obviously is not a lawyer’s office—so there is no reason to use a special master.

Just because any citizen might have attorney-client privileged documents (or, for that matter, doctor-patient information) in their home does not justify appointing a special master. Any protection of attorney-client privileged documents can be handled by the the FBI/DOJ “filter team” already in place to make sure that potentially privileged material is not seen by the investigative team. This is standard operating procedure, and the filter team on this case has already completed its examination of potentially privileged documents seized in the search warrant.

Trump’s legal team may also be trying to conflate executive privilege with attorney-client privilege, but Trump’s assertions of executive privilege have been repeatedly struck down by courts. Moreover, executive privilege is meant to protect confidences of the executive branch from another branch of government seeking information—or from the general public seeking the same—but it is hard to understand how executive privilege can be exerted against the executive branch itself.

But Judge Cannon’s inclination to appoint a special master potentially carries with it a far greater threat to the administration of justice than just being unnecessary. Appointment of a special master in an active criminal investigation creates a strong potential for interfering with how the investigation is conducted.

For example, what if the special master reaches a different conclusion about privilege than the FBI and the DOJ does? Who resolves that conflict, and what happens to the investigation while that conflict is resolved? This type of dispute encourages civil litigation as a tactic to slow down or impede a criminal investigation, and it needs to be nipped in the bud.

It's understandable that Attorney General Garland and the DOJ want to bend over backwards to make sure that they give a former president the appropriate safeguards over potentially attorney-client privileged materials to avoid looking like they are conducting a partisan prosecution. But concerns over appearances must not come at the expense of creating a dangerous precedent for interference with this and future criminal investigations.

The DOJ reaction to the inherent danger posed by Judge Cannon’s inclination to enable Trump’s latest tactic carries with it the risk of further attacks on the DOJ as being “politicized.” But this is a necessary risk. To acquiesce to Trump's tactics over worries about looking “too political” would end up playing right into Trump’s hands. Sometimes worrying too much about appearing political is, itself, being too political.