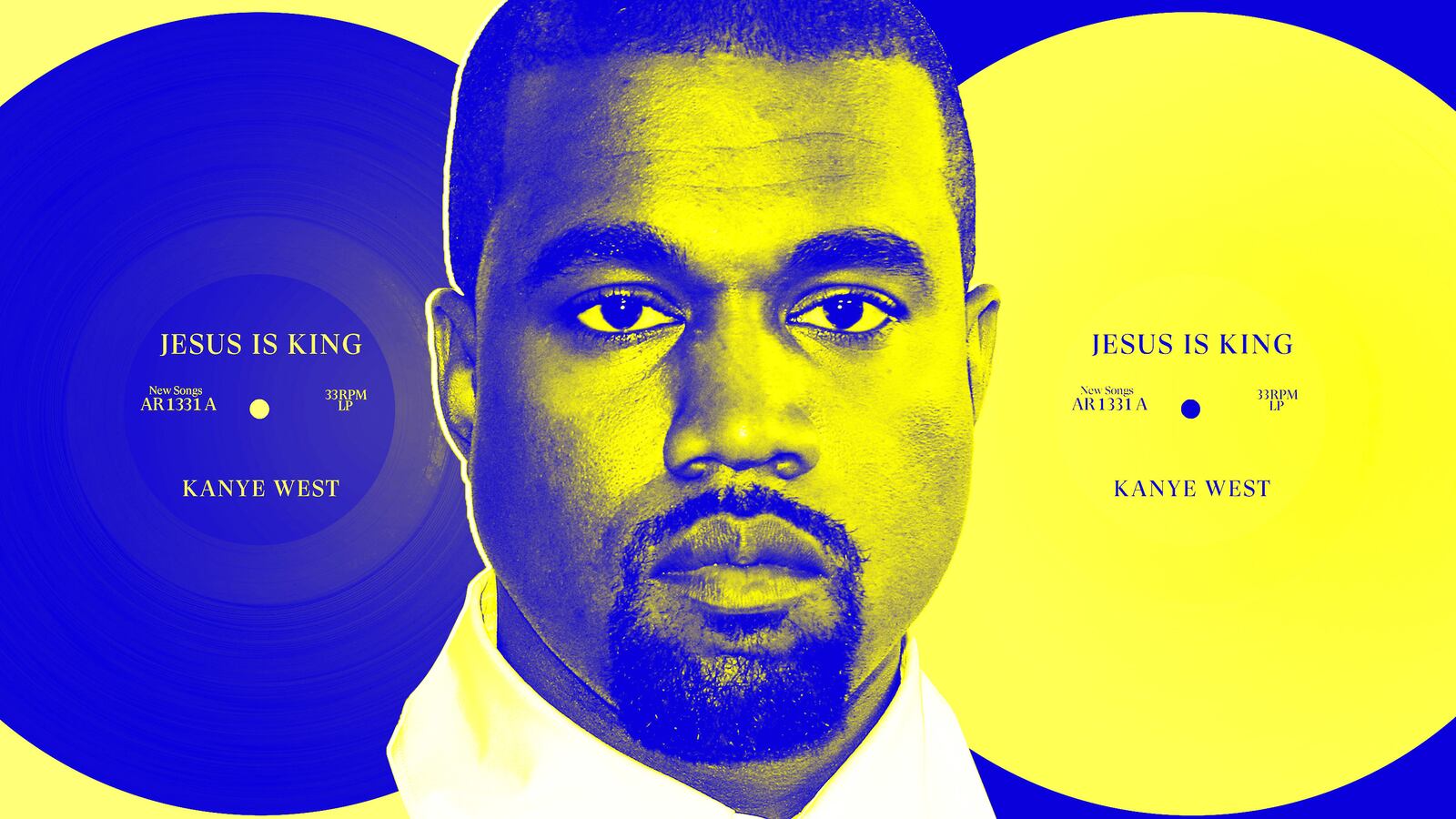

After weeks of false release dates, teased snippets and ridiculous sound bites, Kanye West finally delivered his curiously-anticipated not-exactly-gospel album, Jesus Is King. The album notably comes on the heels of Kanye’s much-hyped Sunday Service shows: a series of gospel-themed performances that grew from private church sessions at his Calabasas home attended by various Hollywood A-listers to West and Co. literally crashing church services and college campuses around the country to perform tracks from the new album. So what to make of Jesus Is King, now that it’s here? The final product of all the chatter over the past few months is underwhelming as a grand creative statement—and inconsequential as a “gospel” album.

Of course, pop artists having spiritual awakenings is nothing new. In 1958, Little Richard renounced rock & roll as “the devil’s music” and walked away from his career at its peak to become a minister. The Jewish-raised Bob Dylan became a born-again Christian in the late-‘70s, releasing albums like Saved before returning to more traditional themes. Cat Stevens converted to Islam and changed his stage name to Yusef. In hip-hop, Run-DMC re-emerged in 1993 with the Christianity-referencing “Down With the King,” while MC Hammer released full-fledged gospel songs like “Pray” and “Do Not Pass Me By.” Artists like Goodie Mob and Lauryn Hill kept Christian themes prominent in their music, while former Kanye collaborator Lupe Fiasco’s Muslim faith permeates his music—as does the Christianity of Chance the Rapper, another Kanye protege.

But Kanye’s religious journey from “Jesus Walks” to Yeezus to Jesus Is King has been an interesting (mostly frustrating) study in celebrity, media and art. “Jesus Walks” was driven by the creativity of former West cohort Rhymefest, who famously walked away from his old friend during the recording of The Life Of Pablo in 2016. Yeezus was seen as the height of Kanye’s egocentrism back in 2013 and has become his most polarizing album. Now we have what many expect to be West’s first full foray into gospel and, well, it just sounds like Kanye being Kanye—with more scripture.

For what it’s worth, Jesus Is King is Kanye at his most tuneful in years. There’s a melodicism that hearkens back to his popular 2000s sound, with the kind of sonic textures he explored (with less consistent results) on 2016’s The Life of Pablo. Forgoing the silly hedonism that dragged down so much of that record and avoiding some of the more pretentious indulgences of last year’s Ye makes this, in a way, the most streamlined Kanye has sounded since his heyday.

But the high points of craft don’t negate the more juvenile moments in what’s supposed to resonate as a grand statement of spiritual purpose. When West croons “You’re my Chick-fil-A...you’re my number one—with a lemonade” on “Closed On Sunday,” it’s groan-inducing. It says a lot about how West comes off in 2019 that such a goofball line from him would have once seemed irreverent.

The “Every Hour” opener is as straight-ahead gospel as the album gets, with West’s Sunday Service choir offering sped-up platitudes. But the Ronny J-produced “Selah” brings us directly into Kanye’s moody trademarks: “When I reach Heaven’s gates / I ain’t gotta peek over / Keepin’ perfect composure / While I scream at the chauffeur.”

Ant Clemons and Ty Dolla $ign show up for “Everything We Need,” a slice of upbeat trap that wouldn’t have sounded out of place on Pablo and began life as a track on West’s shelved Yandhi project. Clemons reappears on the follow-up track “Water,” a slow-groover more meditative than it is explicitly spiritual. “God Is” is Kanye once again wearing the album’s religiosity on his sleeve, with warbled AutoTune vocals conveying some of his most cliché church-isms (“King of Kings, Lord of Lords / All the things He has in store / From the rich to the poor / All are welcome through His door”) and that always present chip on his shoulder (“This my kids / This the crib / This my wife, this my life / This my God-given right”). It’s the core of the album that proves Kanye is only occasionally interested in seeking God’s grace or praising His mercies, and is far more preoccupied with nailing himself to a cross.

An album highlight, the Clipse reunion of Pusha T and No Malice, is an invigorating presence on “Use This Gospel.” Pusha seems less focused on the Lord while his brother, devout Christian No Malice, rhymes, “From the concrete grew a rose / They give you Wraith talk, I give you faith talk / Blindfolded on this road, watch me faith walk / Just hold on to your brother when his faith lost.” The Kenny G sax solo is mostly extraneous, but provides interesting texture on an album that often threatens to run together.

If you’ve been a fan of Kanye’s music of the past five years, there’s a lot to enjoy about Jesus Is King. He’s engaged and sounds more creatively focused than he has in a while. But those are modest triumphs; and if you’ve found recent Kanye to be insufferable and musically hollow, well, this album likely won’t shift your opinion. Kanye adding more Jesus references to his own persecution complex does not a gospel album make, but the rapper seems convinced that his own demands and defensiveness make him a martyr. Jesus Is King isn’t much of a gospel album and it’s only a fairly average rap album. It’s sonically and stylistically on par with much of 2010s Kanye: grand, sweeping-but-empty, and full of the bombast inherent in the artist himself. This time there’s just a little more mass choir thrown in.