“Here’s what’s wrong with us: there’s nothing at stake.”

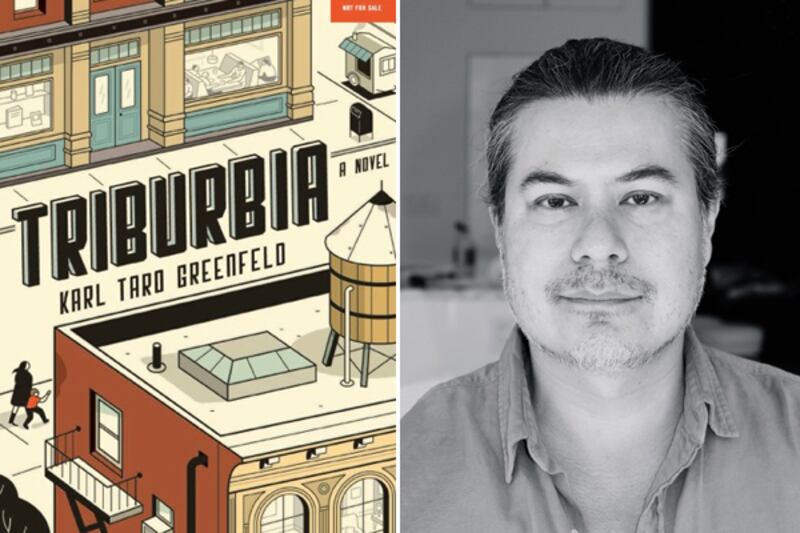

This line appears on page two of Karl Taro Greenfeld’s debut novel, Triburbia. It describes the professional Tribeca bohemians whose conflicts are the novel’s meat. The four paragraphs which follow, lyric and enraged, deal explicitly with gentrification and arrogance, poverty and hypocrisy, and even, a little, the value of art. They are insightful, elegant, and particularly interesting to consider when you read Greenfeld, in a recent interview, saying this:

“There’s a ‘real housewives’ quality to it that I hope makes it commercially viable.”

Triburbia is indeed commercially viable. It is not only a fast read—it also describes part of a tribe which judges, sells, and consumes American fiction professionally. It is thus inherently well positioned. But it is also, fundamentally, a moral novel, concerned with a daily search for meaning and decency. That it is as voyeuristically satisfying as Real Housewives (or John Updike's Couples) is a bonus.

Greenfeld has wide experience as a journalist, and it was in this context that I first met him, in 2003. He was my boss, the editor of TIME Asia, based in Hong Kong. He chronicled the SARS epidemic, wrote stories about meth addicts in Bangkok slums, sent reporters into Burma with Kachin rebels, fought libel lawsuits, and much else. In this context, his devotion to fiction about Tribeca might be surprising, until you realize that Greenfeld believes there is as much “at stake” in novel writing as there is in any of his previous work. This belief is manifest in both the anger and generosity with which Triburbia treats its characters. It is part of what makes the book compelling. It is also what inspired the following conversation, which was conducted via email.

When and how did you write the book?

I wrote the first story when I was still at Sports Illustrated. I began to write about having breakfast with these other fathers, most of whom were writers and artists, but I consciously didn’t want to make it enlightening or a life affirming in any way. I hated the idea of these breakfasts somehow being nurturing. I wanted to capture the adolescent quality of these interactions, that it was more like kids bullshitting and smoking dope while watching afternoon TV than grown-ups engaging in the topics of the day. What I mean is there was nothing redeeming about these interactions besides being a pleasant way to kill an hour or two before heading off to work. So I ended up with a story about how phony much of this interaction was, how pretentious, how self-aggrandizing—not that those traits are inconsistent with a certain kind of witty bantering good time—but that was the germination. And the dark and corrupt human natures that the book explores are essentially all laid in with that story.

I wrote it from there. One story after another, not in the order in which they are published. They are a bunch of stories that fit together and we called it a novel because publishers think novels sell better than collections.

Could you talk about the kids in the book? You write about war between 8-year-old girls, and their cruelty. It is a surprising part of the book, when you leave adult world. Is this harder to write, or what?

The girls in the book are little monsters. I find cruel children to be the most difficult adversaries of all. Not so long ago, and I don’t want to be too specific here, we spent some time at a friend's house and they had a very cruel 11-year old who was unrelentingly dismissive, condescending, insulting, and intimidating. Every interaction with her was fraught lest she would throw a sulk or sink into a pout. She could turn conversations around in such a way that you were suddenly on the defensive for having asked a question like, “do you know where so-and-so is?” She would answer, “You know it’s rude to interrupt people,” when she was sitting there at a computer playing Poptropica or whatever. She was even more impossible for the other children who were around and I could tell they were all carefully avoiding saying anything to upset her, which was impossible because she was so capricious that a compliment could set her off. And this just went on and on and as an adult who is not her parent, what do you do?

That’s why the conflict in the book between the gangster and the very mean 8-year old could be one of the great power struggles of all time—it’s Godzilla versus Mothra. It’s brute, blunt force versus unremitting empty-minded cruelty, only because of the community the gangster lives in, Tribeca, the cruel little girl is actually holding all the levers of power. How does an adult deal with a mean kid? It’s fucking impossible.

Re: empty-minded cruelty—there’s a section where one character thinks about how much one life is worth versus another. Her brother versus a thousand lives. Have you thought a lot about this problem? It’s an old one…

You mean 1,000 wogs, 10 frogs, 1 Brit? That’s how the problem was expressed in journalism. I wasn’t trying to raise a philosophical question, just trying to end a chapter.

That’s one thing that occurs to me about your books, actually, or at least the last three after Twelve, is that you seem more deliberate as a writer than I am. I get the feeling, especially with The End of Major Combat Operations and An Expensive Education, that you choose your words very carefully and that you are, sometimes, actually trying to wrestle with ethics and philosophy and duty and morality. I think part of the reason for that is you are young and—I mean this as praise—have the hubris to attempt to go after that kind of big game. I’m older and less confident about what I know so I think I stalk smaller prey. Not to say I might not end up with a more interesting or better book, but I don’t start out looking at any big issues.

Some come up though: “We dated bankers, artists with trust funds, editors and writers, nobody who knew how to do anything.” One of your characters says that, and “man of action” questions (and economic inequality) come up repeatedly—especially with your gangster character, Rankin—“as if they knew that Rankin was real. Real real. And the rest of them, rich fucks, were full of shit.” Your initial intent aside, how much do you think these issues occupy current American fiction? Think there is a lot of fiction about “real”?

There is an awful lot of fiction about “real.” In fact, I think American MFA programs excel at producing stories about real people doing real things. There aren’t many MFA workshop stories about 40-year old Tribeca playwrights cheating on their wives.

One thing that has perplexed me a little is how some reviewers say they find the characters unlikable. Putting aside the infantile reading level that this sort of observation springs from, I also find that reaction perplexing because I actually LIKE these characters. I like guys who are fuck-ups and have to make up a lie to cover up for the fact that they can’t remember the last lie they’ve told their wives and are late on every deadline or project and can still somehow keep themselves afloat. They are all like con men in a way, but I think every artist, or at least writer, feels a little like a con man in that what we do for a living is something everyone in a literate society can do past the age of, say, 7.

I found interesting this community of men who were fuck-ups with swagger. But the women in the book are not fuck-ups at all. They are the ones who are actually getting shit done. So maybe the book is this strange feminist statement.

Did you read novels while you wrote the book? Which?

I don’t remember what I was reading when I was working on Triburbia. Partly because I probably wrote two dozen short stories and 40 magazine articles in between while I was working on the stories that became the novel. But as Triburbia began coming together as a book I looked at The Wanderers by Richard Price, A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan, Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury, and a few others, mainly for reassurance that these sorts of linked collections were possible—and commercially viable.

Do you think there are elements that make a work of literary fiction (aside from craftsmanship) more likely to be a commercial success? Strikes me that this is the kind of thing that your characters might talk about. And your book is the kind of thing they might read.

We had this conversation the other night and you were saying there were certain boxes you could tick and I was saying it’s all a matter of luck. I was thinking about that today because I did a panel with this woman, a former editor at S&S, who wrote Age of Miracles, which is an amazingly crafted book but one in which I saw those boxes being checked. Apocalyptic? Check. Adolescent female heroine? Check. And the book has been a bestseller. But then we come back to your aside. Craftsmanship! That’s the thing you can’t check off, right? You have to craft, which is fucking hard, or is for me.

So I now sort of agree with you. Perhaps you could check off certain boxes. Zombies. Adolescent female heroine. Serial killers. Distracted detective. I don’t know. And build this commercial book. But I don’t want to write that book. Writing is too hard for me to remove from it the mystery of discovering what a story might be at the end.

Do you find talking about writing useful to the muddling through?

I find talking about writing to be useful only in that it makes me feel marginally better about not actually writing. Nothing is useful for writing but actually writing.

What are you writing now?

A magazine article about ESPN. Talk about mystery.

Full disclosure: in the summer of 2003, I worked in the Hong Kong office of TIME Asia, where Greenfeld was Managing Editor. We became friends and stayed in touch. Later, Karl was Editor-at-Large for Sports Illustrated, which my father, Terry McDonell, oversees as a Group Editor for Time Inc.