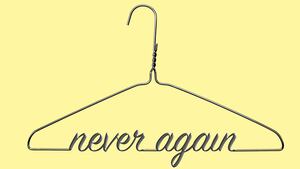

In the 45 years since Roe v. Wade, 60 million American women have chosen to legally terminate their pregnancies in safe, clinical conditions. Prior to 1973 millions had undergone abortions that were illegal and often fatal. The issue that Roe decided was not whether women would have abortions but what kind they would choose—underground procedures or medically supervised ones that protected their health.

But what if this were no longer the case? With Roe in jeopardy, whatever the outcome of the current hearings over Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination, we might want to consider what America would look like if the Right-to-Life forces achieved their long-term objective of re-criminalizing abortion within receptive states and, perhaps one day, across the nation. For this, we need only look back to a time prior to 1973 when abortion was a crime. One of the best guides to this era is The Worst of Times, a small book that provides a bracing reminder of what women seeking to terminate their pregnancies faced in the years before Roe v. Wade.

Although the book is 25 years old, it is perhaps more timely now than when it was written in an era when Roe appeared to be settled law. The author, abortion-rights lawyer Patricia Miller, takes us methodically through a harrowing landscape of illegal abortion that encompasses survivors, practitioners, coroners, policemen and, most devastating, the children of women who died from illegal abortions.

Her subjects, now long-gone, provide first-hand testimony to the furtive ordeal of obtaining and enduring an abortion between the 1930s and the early ’70s when Roe became law. The women are anything but the abortion-on-demand caricatures who use the procedure as a convenient form of birth control. Rather, they are good Americans from small towns and middle-sized cities, embedded in religious communities and among tight-knit families. They cover a spectrum from young girls whose lives would be blighted by an unwanted pregnancy, to abused wives who no longer want another child with a feared husband, to beleaguered mothers too poor to raise yet another infant, to women burdened with already large families.

Far from the promiscuous slattern of anti-abortion fantasy, they encompass a cross-section of the “real Americans” that we hear so much about from politicians. Although their stories are distinct, the common thread that binds them is their trepidation at the prospect of an abortion, their sense of isolation, their determination to go ahead whatever the cost, and their sense of relief when it is over. A 1955 survey estimated that between 800,000 and a million women underwent abortions that year—about as many as are performed today.

Abortionists themselves presented a diverse array ranging from hairdressers, dairy farmers, barbers, motorcycle mechanics and back-alley practitioners to part-time nurses and doctors who risked their licenses, some for the money and others out of a sense of dedication. One of these was Dr. Robert Spencer who practiced in the mining town of Ashland, Pa. He was a respected figure in the community, conducting a regular practice in the day and an abortion facility during separate hours. He forewent his fee for women who couldn’t afford one.

But all too often, women would face terrifying experiences at the hands of indifferent strangers in sordid backwaters. Illegal abortion proved a boon for organized crime. Like Prohibition, as was famously noted, it made criminals millionaires and ordinary citizens criminals. Desperate women had few safe options.

Doctors, fearing loss of license, refused to perform the procedure. The result was often botched abortions whose victims appeared in hospital wards with fatal complications that doctors later lamented as “tragic.” As one physician said, recalling his reaction to the death of a young woman who’d been brought in after a septic abortion: “I thought the solution was to jail the abortionist. It took me another 20 years to understand that it was the system, not the abortionist, who had killed her. The lawmakers who left her with no choice killed her just as surely as if they held the catheter. It was all so unnecessary.”

The sites for abortions were wide-ranging as well, from the backs of cars and kitchen tables to seedy attics and dark basements, to the back rooms of medical facilities. Women tried home remedies or resorted to caustic chemicals. Many opted for mechanical procedures. The instrument of choice, generally, was a catheter, which, if things went well, would eventually eject the fetus from the uterus. If things went badly, the uterus could be ruptured or, because the instruments were unclean, infected. This could result in hemorrhaging, sepsis, shock and death. Before Roe, the death rate from abortions was staggeringly high—and many families, to avoid embarrassment, and hospitals, to evade complicity in treating a woman dying from complications, often cited “renal failure” or some other such euphemism as the cause of death. After 1973, under safe medical conditions, it plummeted.

As harrowing as are the first-person accounts of the women seeking and undergoing illicit abortions during this era, the recollections of adults who, as children, lost their mothers to illegal abortion are almost unbearable to read. Jane, herself an aging woman when she recounted her story, says: “There aren’t words to describe the impact illegal abortion had on my life.” She was 12, the eldest of six children in a hardscrabble Methodist family in Nebraska when her mother bled to death in 1932 after an illegal abortion, “leaving six motherless children who needed her desperately.” After her mother’s death, the children—the smaller ones terrified—were dispersed among relatives or sent to orphanages. Some never saw each other again. “I lost my mother,” Jane says, whom she recalls as “a very sweet, gentle woman,”“but she adds that “I lost my brothers and sisters as well.” Even those who reconnected as adults “lost the precious childhood memories of growing up together.” “I’m 70 years old now,” she says, “and the pain I feel hasn’t faded for half a century.”

Illegal abortion had collateral damage—thousands of orphaned and broken families—that surely must be taken into account by a Religious Right that espouses family values while seeking to deprive women of safe medical abortions. They profess compassion for the pain of a fetus, but show little sympathy for the lifetime of anguish that living human beings may endure because of an unwanted pregnancy, or the suffering of entire families from the fatal consequences of back-alley abortions.

Brett Kavanaugh remarked at his nomination hearings that he would be guided by history and tradition in applying the Constitution to the cases before him. In this light, we should be aware that until well after the Civil War, abortion was legal and widespread in this country. This norm was based on English Common Law, which permitted ending a pregnancy before “quickening”—when a woman can actually feel movement, usually about 20 weeks. Abortion providers and home remedies proliferated during these 75 years among “white, married, upper-middle-class native-born Protestant American women.” During this period, Patricia Miller writes, “abortion was a service publicly traded in the free market by recognized practitioners who were not doctors.” It was the intense competition from “real doctors,” many of whom themselves lacked medical degrees in those free-wheeling days, that ultimately drove their unsanctioned rivals underground.

The American Medical Association had some well-publicized help from the Gilded Age zealot Anthony Comstock, better known for his crusades against prostitution and pornography as the head of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. In the 1870s Comstock led a successful campaign making it a federal crime to disseminate any contraceptive devices or print information on how to get an abortion. “‘Comstockery,’“ Miller writes, “did more than anything else to drive abortion underground, where it was to remain for more than 100 years.” By the 1880s anti-abortion laws were instituted across the country.

During this period, organized religion began to weigh in on the issue as well. Presbyterians called abortion “a crime against God and Nature.” And in 1869 Bishop Spaulding of Baltimore decreed what was to become the official Catholic position for the next hundred years: A woman was not permitted to abort a child under any circumstances, “not even for the sake of preserving her own life.”

It may be worth noting that many of Miller’s subjects come from the small towns and cities of Pennsylvania where she did considerable research. The author could not know at that time about the recent Grand Jury report that would expose the abuse of more than 1,000 children during a period of 70 years by more than 300 priests in the same region. Which means that for at least 25 years before Roe, the very same church in Pennsylvania that was upholding the cause of the unborn was protecting hundreds of predators who were preying on the born. The saving Grace of Miller’s chronicle is the humanity shown by so many Catholic and Protestant laymen in these communities who surreptitiously ignored religious doctrine and showed true Christian compassion by flouting the law and aiding women in desperate straits.

To be sure, the objection to terminating a pregnancy is a deeply held conviction worthy of respect and consideration for its adherents. It is rooted in Scripture, most notably in such majestic passages as Jeremiah 1:5, “Before I formed you in the belly I knew you, and before you left the womb sanctified you” and Psalm 139: “You have covered me in my mother’s womb... Your eyes saw my unshaped form, and in your book all were recorded; though they are fashioned through many days, to Him they are one.”

These are beautiful and elegant passages, giving life sanctity at conception, and providing meaning for generations of believers. As inspiration for the faithful they are estimable. As the basis for law in a secular society they are less so. It is understandable that for those who believe life begins at conception, and that quickening is simply a stage in a life already started, abortion is nothing less than murder. But they are not right to impose their religious doctrine on others who do not share their views. That is the basis of the First Amendment guaranteeing freedom of conscience.

Brett Kavanaugh’s understanding of birth control as “abortion-inducing drugs” springs from the theological concept of life beginning at conception. Ignoring, for a moment, the assumption that preventing a potential life is equivalent to ending an actual one, Kavanaugh’s sincerely held belief is consistent with the credo that abortion is murder. In this light, there is a certain logic to his patron Donald Trump’s recent musing that women who have abortions, as well as the practitioners themselves, should be punished. While seeming far-fetched today, it was this very fear that terrified so many women seeking abortions before Roe v. Wade.

Hardly more than a year after Roe, Richard Nixon was driven from office in the Watergate scandal and the GOP suffered significant losses in the 1974 congressional elections. Sen. Jesse Helms of North Carolina, looking for a strategy to re-energize the Republican base,

introduced an anti-abortion plank to the party’s platform, which became a regular aspect of the GOP program and an effective tool in rallying the party faithful. Over the next four decades, the Republican legislative campaign was accompanied by a legal one to eviscerate Roe with victories in Webster (1989) and Casey (1992) that allowed states to expand restrictions on abortion. The Right-to-Life movement is now within striking distance of vitiating Roe.

If it succeeds, we might consider what a post-Roe America could look like. To be sure, the country is far different now than it was half-a-century ago. Two generations of American women now see access to safe medical abortions as a right. To subvert that right would likely create legal havoc, a political maelstrom and a surveillance challenge that would be daunting to enforce. Perhaps those who would suffer most would be low-income women in red states who lack the means to have ready access to abortion facilities. By invoking women’s safety as a justification for imposing restrictions that would curtail abortion services, Right-to-Life proponents would actually be creating conditions that would threaten women’s health.

Should Judge Kavanaugh survive the current vote and be appointed to the high bench, it would be nice to take comfort in his reassurance that he will consider history and tradition in deciding constitutional issues. The question is whose tradition? Is it the tradition of religious tolerance imbued by Roger Williams, or that of the Puritan Elders and their sectarian dogmatism? The Enlightenment rationalism of the Founding Fathers, or the religious enthusiasms of the Second Great Awakening? Is it the America of repression espoused by Anthony Comstock, or the America of compassion embodied by Margaret Sanger? There is not one single tradition but many, and if Judge Kavanaugh is elevated to the Supreme Court, it would behoove him to thread his way humbly among them. He might also do well to heed the counsel of his predecessor on the high bench, Harry Blackmun, who spoke for the court majority on Roe with the following words:

“We recognize the right of the individual, married or single, to be free from unwarranted government intrusion into matters so fundamentally affecting a person as the decision whether to bear or beget a child. That right necessarily includes the right of a woman to decide whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.” This decision, guaranteeing safe medical care for women seeking an abortion, is now part of American tradition and history. One can only hope that, whatever the Supreme Court’s complexion, the justices acknowledge it as established law.

Jack Schwartz is a former book editor of Newsday.