Keith Miller was headed for an enviable position in the NFL—until the velvet-voiced gridiron star was serenaded by the opera. He talks to Eve Conant about exchanging his helmet for tights.

Meeting Keith Miller for the first time backstage at the Washington National Opera, in a black kimono and Japanese Tabi slippers, he comes across as a gentle performer with a voice that impresses, even when just speaking quietly.

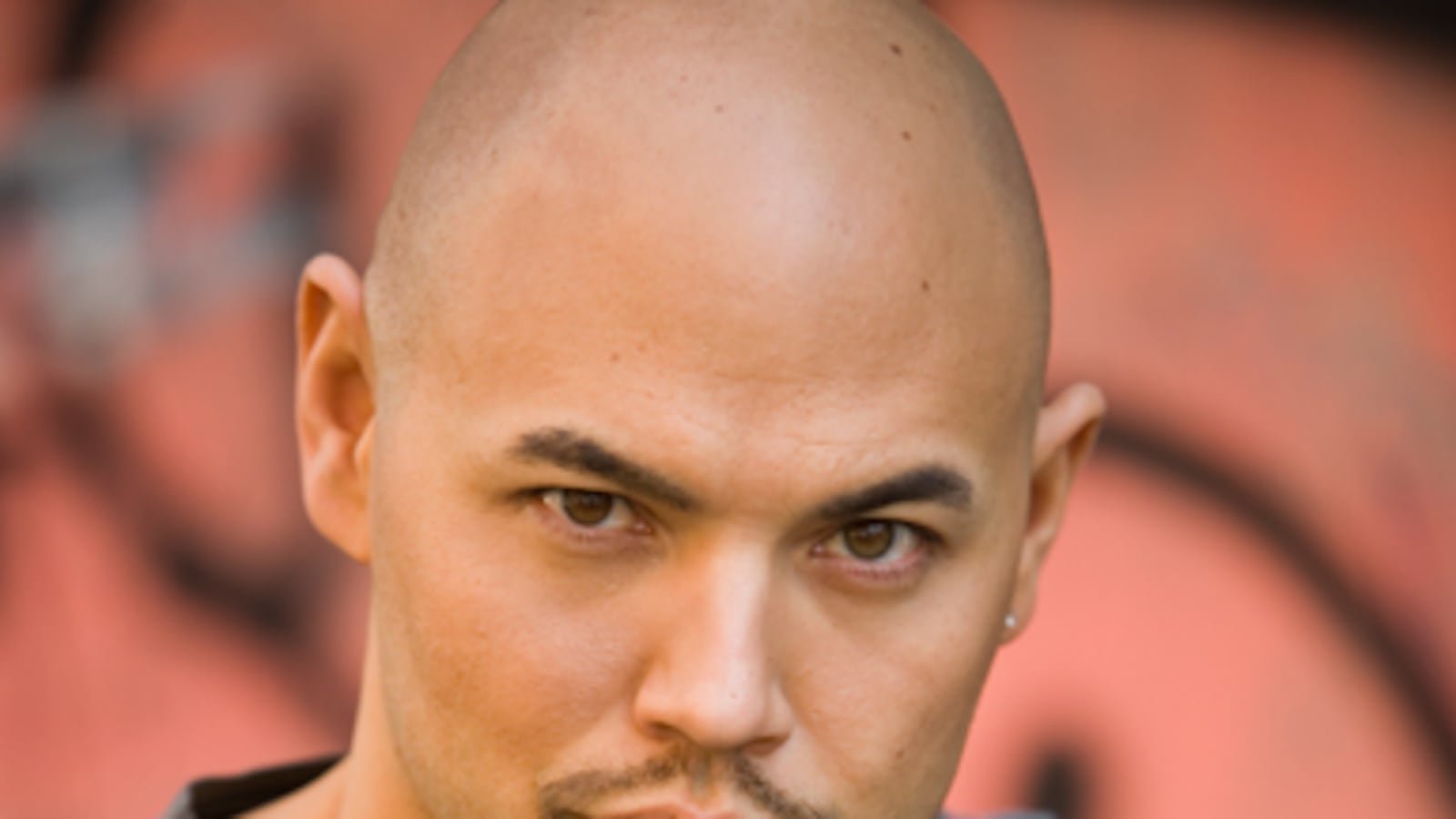

But if you were to look at his old driver’s license? In that hulking mug shot is a man who weighs 265 pounds and sports a menacing Fu Manchu goatee. The photo barely resembles the now 220-pound budding opera star who will sing a commanding solo when Madame Butterfly opens in the nation’s capital next week. If there is a disconnect, it’s because Miller’s rise in the rarified world of opera has been about as swift and surprising as it gets.

At 37, he’s been part of some 200 performances at the Metropolitan Opera, where he’ll return for the fall season this year after debuts in D.C., Seattle, and the Glimmerglass festival in New York. Opera News has hailed his “smoldering presence and sharp, booming delivery” and called him an “artist to watch.” That might not sound too unusual, except for the fact that the ex-athlete only learned how to read music nine years ago, and that was by teaching himself.

Miller, it turns out, was a pro football player.

The former starting fullback still bristles when he recalls the locker room taunts he had to endure when he first fell in love with opera. “Let’s just say the most watered-down one was ‘sissypants’ and the others had to do with questioning my manhood and sexuality. I can’t even say the other words, they’re too bad for print.” That was back in 2001 and 2002, when he was still angling for an NFL career, working out with professional teams like the Denver Broncos after an impressive run at the University of Colorado, where he excelled in four college bowl games.

Miller’s unlikely rise to opera stardom begins as many success stories seem to begin—in a tiny town no one has ever heard of. In his case it was Ovid, Colorado, with a population that hovers around 300. His family was strict, and there was little music in the home, as “kids were meant to be seen but not heard.” He played a bit of flute (and for a brief stint, tuba) in the high school band with just a rudimentary sense of the instruments. And that was only because Miller had a crush on another flute player.

One night during his years as a college fullback he took his girlfriend to see Phantom of the Opera. It was a life-changing moment.

He found his true path with football; his team came in first in the country for six-man football his senior year. The football success continued through college and in the years after, but one thing kept creeping in—a strange and unexpected love…of opera. One night during his years as a college fullback he took his girlfriend, a basketball player, to see Phantom of the Opera. “I just thought it would be a cool date,” he recalls. Instead it was a life-changing moment.

After that night he listened to and sang along with all the musical theater he could, eventually renting The Three Tenors on DVD, where Luciano Pavarotti floored him with his singing of Puccini’s classic Nessun Dorma. “That’s when I fell in love,” says Miller. When he wasn’t on the field, he could often be found in the music library at the college, wearing his football letter jacket as he tried to copy out piano and vocal opera scores in a slow and painful attempt to learn to read music. A sympathetic librarian introduced him to an increasingly complicated repertoire, culminating with Mozart’s Don Giovanni and recordings of Samuel Ramey, a legendary bass singer.

Miller was four credits short of graduating when he began playing football in Europe and later with U.S. spring football leagues, working out with teams like the Oakland Raiders and the Broncos. When several Bronco players were injured, Miller thought he was close to making the cut. But while training in Fargo in 2001, he noticed a flyer for auditions for the young artist program at Pine Mountain Music Festival in Michigan. He went for it—singing one aria.

By the time Miller had driven home, the messages on his answering machine included offers for five roles in area opera companies, and a spot with Pine Mountain. He made the mental switch, deciding to pin his hopes on music, not the gridiron. Yet once at Pine Mountain, he was told he needed more serious training and soon landed a coveted spot at the rigorous AVA—Academy of Vocal Arts—in Philadelphia. Miller describes it as akin to an opera “boot camp,” where instructors intentionally break you down only to build you back up, leaner and meaner.

Still, it was hard to let go of sports, even as he recognized that “football is not a career known for longevity.” It also wasn’t a career with much tolerance for opera, yet his time on the field taught him to be tough, persistent, and unafraid of learning new definitions of strength. “I had found this non-macho thing to do when I was supposed to be a macho jock. Even I had moments when I was like, ‘You mean I’ll be walking around in tights and makeup?’ But in the end it all builds you up. Your costume is just like your uniform.”

Eventually Miller came to terms with the shift. “You have to not care what people think, to let yourself love something that is bigger than you. Even if someone has three Super Bowl rings on their finger, that doesn’t mean they are stronger than me.” But he took his share of taunts from the opera crowd as well. “I’ve been called a jock, or—when I was first starting out—just ‘stupid’ because I didn’t have an education in music.” But he’s since been embraced by the opera world, and as for those former operatic naysayers, says Miller—sounding, sorry, just like a jock—“I outworked them.”

In fact, Miller is trying to get opera singers—known for large bellies and not-exactly-rigorous physical regimes—to shape up. He’s created a new workout regime for opera singers, called Puissance Training (Meaning “Power” in French) to help train them for physically demanding roles and scenes, such as stage fighting or dances. He’s training artists young and old, and is raising money for a training facility in New York City, where he’s based. And in yet another sign of how football and opera can mix, he’s doing the training with the help of a business partner, one of his former football trainers.

“There’s been no place for opera singers to physically train for opera, they think yoga or pilates will help with their core strength, but it’s not about core—its about air and breathing.” Miller says. Instead, he’s modeled his training on Lamaze classes, teaching singers how to breathe while in stressful physical positions, and train their bodies for specific physical roles or other challenges—like altitude. “If your voice backs up or freezes up on stage, that can be dangerous for a singer.” (Maybe some of those lip-synching pop stars who fear getting out of breath should explore his new method.) As for Miller, he is in supreme shape, lifting weights and working out as he did in his football days. The result, he boasts, is that “I can do things no one else can do on the stage.”

He’s still a newcomer, and a late one, to opera. In a business where many singers begin training as children, Miller did his early work, and made his first debut, in his 30s. His roles at the Met have been many, but they’ve so far been small. He doesn’t expect to get a shot at leading roles until his 50s, and he’s patiently letting himself be groomed until then. Miller likens the Met’s technique to “drafting a really good lineman, but out of high school.” Another lesson he’s learned from football: “You can’t make up for experience, and you have to pay your dues.”

Eve Conant is a Newsweek staff reporter covering immigration, politics, social and culture issues.