When a novel becomes a “classic”—when it is digested by critics and English teachers and study guide authors into bite-size morsels that can be slurped with a spoon—it undergoes a peculiar type of transformation. For one, it ceases to resemble a novel. Even the messiest, most obstreperous books are reduced to a litany of bullet points, or a single bullet point. Moby-Dick: Obsession devours. Crime and Punishment: Guilt corrupts. White Noise: Technology numbs. It can be disorienting to actually read the damn thing, and find out the epitaph is no more descriptive than a chapter title, and a misleading one at that.

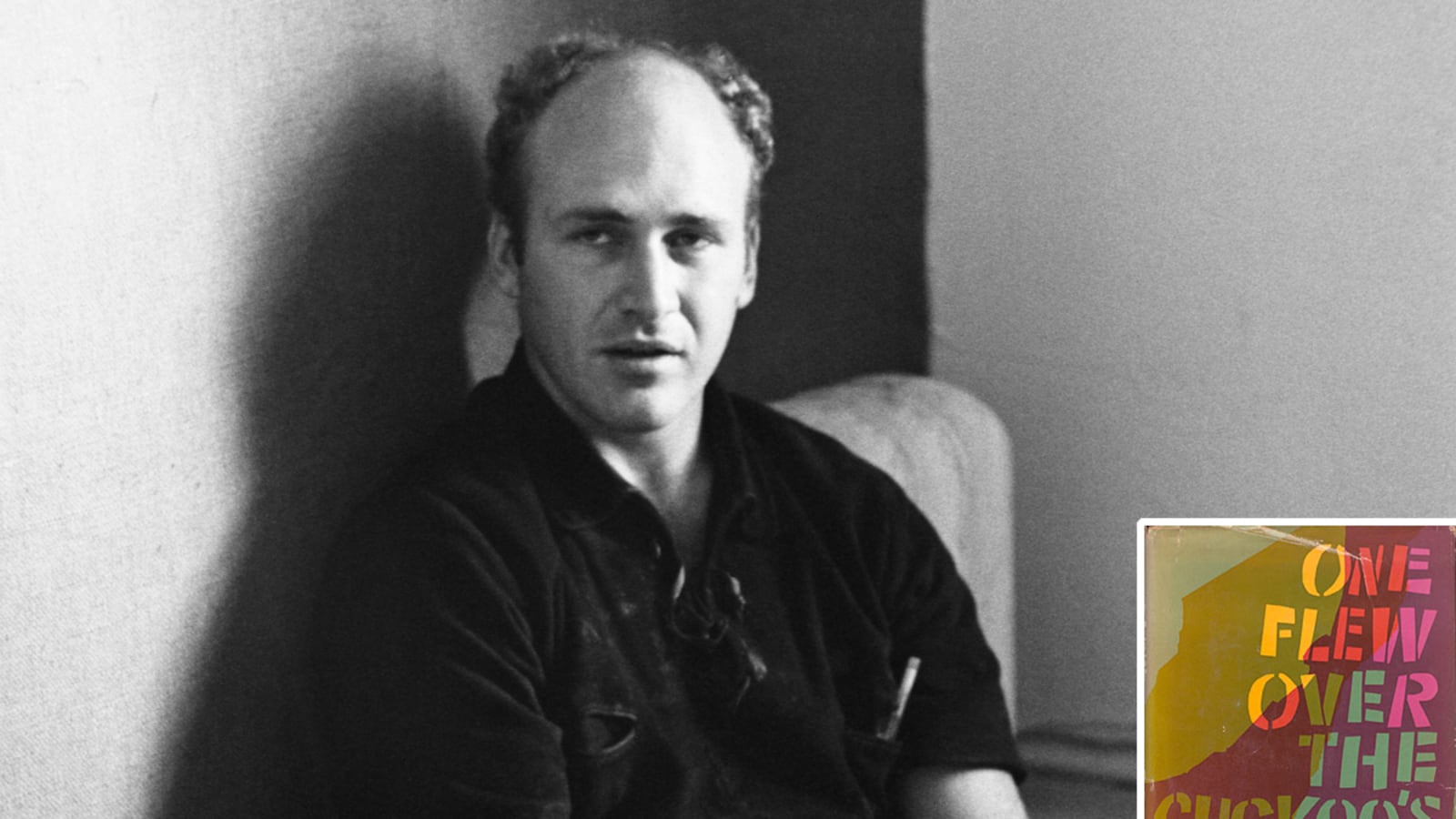

It’s even worse when the novel is adapted into a film, especially a good film, as is the case with Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Since Milos Forman’s adaptation, the line about the novel has been that is an “antiauthoritarian fable” (Larry McMurtry), a “nonconformists’ bible” (Pauline Kael), “a metaphor of repressive America” (Christopher Lehmann-Haupt). This view is accurate—Kesey is certainly interested in conformity and its discontents—but incomplete. What Kesey has to say is larger, and far more subversive.

Kesey is not the first author to write about lunatics who appear saner than those who seek to lock them up. The trope dates back as far as Don Quixote, continues through Mary Wollstonecraft’s Maria, or The Wrongs of Woman, Gogol’s “Diary of a Madman,” Vladimir Nabokov’s Invitation to a Beheading, and Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, published a year before Kesey’s novel. The nature of the oppression is different in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, however: the inmates in Kesey’s mental ward, with one or two exceptions, have asked to be locked away. “Guilt,” says Harding, one of the patients, when asked to explain his decision:

"Shame. Fear. Self-belittlement. I discovered at an early age that I was—shall we be kind and say different? I indulged in certain practices that our society regards as shameful. And I got sick. It wasn’t the practices, I don’t think, it was the feeling that the great, deadly, pointing forefinger of society was pointing at me—and the great voice of millions chanting, 'Shame. Shame. Shame.' "

This is a novel about oppression, but it is also about man’s desire—which at times can become a need, even a compulsion—to take orders. Harding’s explanation horrifies Kesey’s hero, Randle Patrick McMurphy, a charismatic huckster whose arrival at the beginning of the novel disrupts the quiet, domineering rule of Nurse Ratched, the ward’s authoritarian overlord. McMurphy tells his fellow patients that, in order to avoid a hard labor prison sentence, he has convinced authorities that he’s a psychopath. “If it gets me outta those damned pea fields I’ll be whatever their little heart desires, be it psychopath or mad dog or werewolf…” McMurphy, despite his swagger, is looking for safety too.

But what kind of safety do Kesey’s inmates find? The novel is narrated by the half-white, half-Indian Chief “Broom” Bromden, who has been committed since World War II—nearly two decades. He pretends to be deaf and dumb, but he sees, and tells the reader, everything. He even sees things that are not there. Machines, in particular. Gears grind, huge brass tubes disappear upward in the dark, and the wall clocks speed up and slow down according to Nurse Ratched’s whim. The nurse and her staff are robots, their power extending “in all directions on hairlike wires too small for anybody’s eye but mine.” Sometimes the Chief even pictures the wall sliding up to reveal “a huge room of endless machines stretching clear out of sight, swarming with sweating, shirtless men running up and down catwalks, faces blank and dreamy in firelight thrown from a hundred blast furnaces.” And at night he imagines that the nurse’s minions operate a machine that chokes the room with dense fog.

There’s an unsubtle lesson here about the mechanized nature of modern American society, man turned into a cog in an intricate machine—the “metaphor of repressive America” in bold type. But Kesey makes a subtler point here as well, one that becomes more insistent as the novel progresses. The devices that Chief Bromden perceives in the walls aren’t just any old machines. They’re war machines.

The fog machine, for instance, is connected to Chief Bromden’s earliest memories as a soldier. “Whenever intelligence figured there might be a bombing attack, or if the generals had something secret they wanted to pull,” he says, “they fogged the field.” Elsewhere the fog resembles mustard gas, the kind used on the battlefields in southern Italy where the Chief was stationed. He believes that the psychiatric pills given to the patients are in fact microchips “like the ones I helped the Radar Corps work with in the Army,” and imagines Nurse Ratched firing a shotgun loaded with thorazine and librium.

The Chief is not the only patient who lives in a fog of war. Old Colonel Matterson thinks he’s still in World War I. Billy Bibbit suffered a breakdown in ROTC training when he couldn’t answer the drill officer’s command without stuttering. McMurphy, who received a dishonorable discharge in the Korean War for insubordination, likens group therapy to his time in “a Red Chinese prison camp”; when he is being hauled in for shock therapy, he says sarcastically that he regrets having “but one life to give for his country.” Even Nurse Ratched, we are told in passing, received her training as an Army nurse.

Kesey suggests that war is not only a cause of the patients’ trauma (“I was hurt by seeing things in the Army, in the war,” says Chief Bromden), but a result of it. The mechanization of society leads, inevitably, to a militant society. This is what happens in the ward, after all, where the patients wage an insurgency against Nurse Ratched and her staff. “She’s lost a battle here today,” says the Chief after one early skirmish, “but it’s a minor battle in a big war that she’s been winning and that she’ll go on winning.”

When Kesey wrote the novel, the Korean War was still fresh in recent memory, and World War II not far behind it. Kennedy was ordering the invasion of the Bay of Pigs. The first American special forces were being shipped to Vietnam. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest may have served as the “nonconformists’ bible” during the sixties, but the connection Kesey draws between conformity and the capacity to wage war remains provocative today. Since the novel’s publication 50 years have passed. The U.S. has been at war for every single one of them.

Other notable novels of 1962:Another Country by James Baldwin Something Wicked This Way Comes by Ray Bradbury The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick The Reivers by William Faulkner Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov The Slave by Isaac Bashevis SingerMother Night by Kurt Vonnegut

Pulitzer Prize in Fiction:The Edge of Sadness by Edwin O’Connor

National Book Award in fiction:The Moviegoer by Walker Percy

Bestselling novel of the year:Ship of Fools by Katherine Anne Porter

This monthly series will chronicle the history of the American century as seen through the eyes of its novelists. The goal is to create a literary anatomy of the last century—or, to be precise, from 1900 to 2012. In each column I’ll write about a single novel and the year it was published. The novel may not be the bestselling book of the year, the most praised, or the most highly awarded—though awards do have a way of fixing an age’s conventional wisdom in aspic. The idea is to choose a novel that, looking back from a safe distance, seems most accurately, and eloquently, to speak for the time in which it was written. Other than that there are few rules. I won’t pick any stinkers.

Previous Selections:1902—Brewster’s Millions by George Barr McCutcheon 1912—The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man by James Weldon Johnson 1922—Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis1932—Tobacco Road by Erskine Caldwell1942—A Time to be Born by Dawn Powell1952—Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison