After months of planning, weeks of frenetic negotiating, and days of doubtful speculation, House Republicans on Wednesday passed a bill—barely—to lift the federal government’s debt limit and drastically cut spending.

Now comes the difficult part.

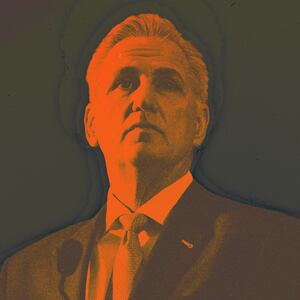

The hard-fought “Limit, Save, Grow Act” is merely Speaker Kevin McCarthy’s opening bid to kickstart negotiations with President Joe Biden to secure deep budget cuts in exchange for not crashing the U.S. economy by refusing to raise the debt ceiling. Biden has said he will negotiate over spending, not over the debt limit.

With time running short until the federal government risks fiscal calamity—with the borrowing limit coming as soon as June—McCarthy now has his bargaining chip in hand to try and force Biden to the negotiating table and attempt to work out some compromise.

But the GOP’s struggle to simply reach the starting block in a unified fashion means their road ahead could be far more difficult than expected.

To cobble together the bare-minimum 217 votes needed to pass the Limit, Save, Grow Act, McCarthy had to agree to hard-right conservative demands, like even stricter work requirements for recipients of food stamps and other forms of poverty aid.

Winning them over was painstaking, with the speaker and his top deputies working the House floor until the vote closed on Wednesday. Four conservative lawmakers voted no, the maximum McCarthy could lose while still passing the bill. Several more voted for it, but tepidly, and having spent days pointing out the legislation’s flaws.

In an ironic show of the bill’s tenuous support, the deciding vote was the scandal-plagued Rep. George Santos (R-NY)—a pariah from whom GOP leaders have repeatedly distanced themselves.

Santos, who told reporters on Friday that he was “solidly” against the measure, found a way to be decisively for it.

Still, Republicans were almost immediately hailing the bill’s passage as a positive development.

“I remain optimistic,” said Rep. Mike Johnson (R-LA), a member of House GOP leadership. “I know very well those who did not vote yes with us today, and I know their concerns, and we’ll be working on that.”

The vote breakdown made a useful point, said Rep. David Schweikert (R-AZ), in making clear to Democrats they “need to be serious about where our votes are.”

“Yes, it may be an opening bid, but there may not be a lot of margin for movement,” Schweikert said. “And, you know, it may not be the best final offer, but it’s a start.”

A leading GOP moderate, Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick (R-PA), said the struggle didn’t influence his view on the prospects for a debt limit deal. “Because we all know how this ends,” he said. “It’s going to end with a two-party solution, unfortunately at the last minute.”

But in achieving some measure of unity for now, McCarthy may have shown how distant his conference is from a solution that would be palatable to the Democratic-led Senate and White House.

Privately, some Republicans believe that if the task of getting on the same page for a party-line opening bid was this hard, attempting to get the party behind a compromise could be impossible.

Many Democrats certainly feel that way. “It’s notable that the only way they could pass this was to make it even more extreme.” Rep. Jared Huffman (D-CA) told The Daily Beast. “That tells you a lot. If they want to do something as a caucus that has the Republican name on it, it’s either extreme, or it doesn’t happen.”

Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT) told Politico, meanwhile, that the House GOP’s exertions were “a clear indication of how disastrous a negotiation could be. I mean, these guys can’t negotiate amongst themselves.”

Few Republican lawmakers were under the illusion that anything resembling the Limit, Save, Grow Act would become law. Fitzpatrick called it “a mechanism to get a sit down between the President and the Speaker.”

Indeed, the bill that passed Wednesday was a grab-bag of Republican priorities, all melded into a package that pleased some and pissed off others. As written, McCarthy’s bill would broadly lower federal spending, cut back on social welfare programs and clean-energy tax credits, roll back huge swaths of Biden’s signature Inflation Reduction Act, and rescind unspent COVID funds.

Poison pills threatened the bill’s passage—like energy provisions targeting ethanol and heightened work requirements for social welfare programs that were too low for some conservatives’ taste.

But true to his negotiating form, McCarthy agreed to revisions to the bill on those fronts, despite his leadership team earlier insisting they would not entertain changes to the bill once written.

That strategy resulted—legislatively speaking—in a win for Republicans on Wednesday. It may also open the GOP up to a number of potent messaging attacks.

Rep. Ruben Gallego (D-AZ), who’s running for Senate, was overheard leaving the chamber Wednesday while telling another Democrat that the bill Republicans had just passed was “a campaign commercial right there.”

“That’s dumb as shit,” Gallego said.

The drama also hinted at some potential fault lines for the GOP, even if the party largely came together on this vote.

“The infighting,” quipped Huffman, “has been postponed.”

When McCarthy was scrambling across four days in January to secure the speakership, conservatives agreed to support him in exchange for assurances that he would open up the legislative process—make it more transparent and pliable for rank-and-file members who had complained about having no influence during the reign of Nancy Pelosi.

McCarthy agreed.

“From the committee room to this floor, we commit to pursue the truth passionately and embrace debate. No more one-sided inquiries. Competing ideas will be put to the test in public so that the best ideas win,” McCarthy said while accepting the speaker’s gavel.

But months later, GOP leadership hardly followed that idealistic procedure for this debt ceiling bill—and the self-described principled conservatives who demanded change hardly balked because they were getting their way.

At first, Republican leadership publicly insisted the bill as released would be its final version. Then, members from Iowa objected to part of the bill targeting ethanol tax credits. And Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-FL) objected over work requirements. And moderates were iffy about the crackdown on social welfare programs, among other provisions.

But instead of following his promise for “competing ideas” to be “put to the test in public,” tweaks to the bill were made in a series of closed-door meetings—sometimes in the dead of night.

Between Tuesday and Wednesday, an overnight overhaul emerged on the bill’s proposals before it went to the floor for a vote Wednesday afternoon.

There were signs the process had chafed on a GOP rank-and-file membership that prides itself on making the House more open and democratic. “It’s a better process than it’s been,” said Rep. Tim Burchett (R-TN), one of the four Republicans to vote no. “It’s just—set-in-stone kind of things don’t always work and are not set in stone for certain people.”

Asked if he thinks that happened with the debt bill, Burchett quickly said “no” before walking into the House chamber.

Most lawmakers, however, seemed inclined to justify the top-down approach as a necessary evil. “There was a lot of communication on this bill,” said Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA). “Probably the most communication I’ve seen on a bill yet.”

From here, McCarthy and his GOP allies—including Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY)—have a stronger hand to ratchet up the pressure on Biden to negotiate. Republicans can rightfully note that, if Democrats want to raise the debt limit, there’s always a House GOP-passed bill sitting in a Senate filing cabinet somewhere.

But House Republican leadership will have to undertake the difficult work of keeping a strident conservative wing on board if faced with compromise—or, potentially, resolute Democrats who refuse to budge.

The stakes, of course, are only the health of the U.S. economy and the federal government’s creditworthiness for the future—both of which are on the chopping block if there is not a timely extension of the government’s borrowing limit.

On Wednesday, McCarthy got sympathy from an unlikely source: Rep. Steny Hoyer (D-MD), the former Democratic Majority Leader. He told The Daily Beast that he doesn’t necessarily believe the GOP’s struggle to pass the Limit, Save, Grow Act is a sign of continued dysfunction.

“I believe that McCarthy is in a tough spot,” Hoyer said. “And he’s trying to work toward what he believes is the ultimate outcome that’s essential. He said default is not an option. He knows that.”

But Hoyer distilled McCarthy’s problem: “His members, apparently, are prepared to default if we don’t agree with something they know we don’t agree with.”

Many Republicans say they are not, in fact, prepared to default. But they remain frustrated that their argument—that a high-risk negotiation with the economy at stake could help the economy in the long run—is not breaking through.

“What really should be the story is the fiscal picture is just really ugly, and we don't seem to be willing to tell that story,” said Schweikert. “So I actually think a knock-down, drag out fight here, it’s actually good. Even though it makes people nervous, it forces them to deal with the reality.”