In a Capitol Hill auditorium last week, Republican and Democratic lawmakers came together and listened to an official briefing on the federal budget. Then they verbally sparred and swapped thoughts about it afterward.

If that sounds like a mundane scene for Congress, it isn’t—in fact, most of the people in the room couldn’t remember anything like it happening in their entire congressional careers.

“I’ve been here a decade,” said Rep. David Schweikert (R-AZ). “I don’t think I’ve ever had that happen before, where it was both parties listening, and then both parties going up to the microphone.”

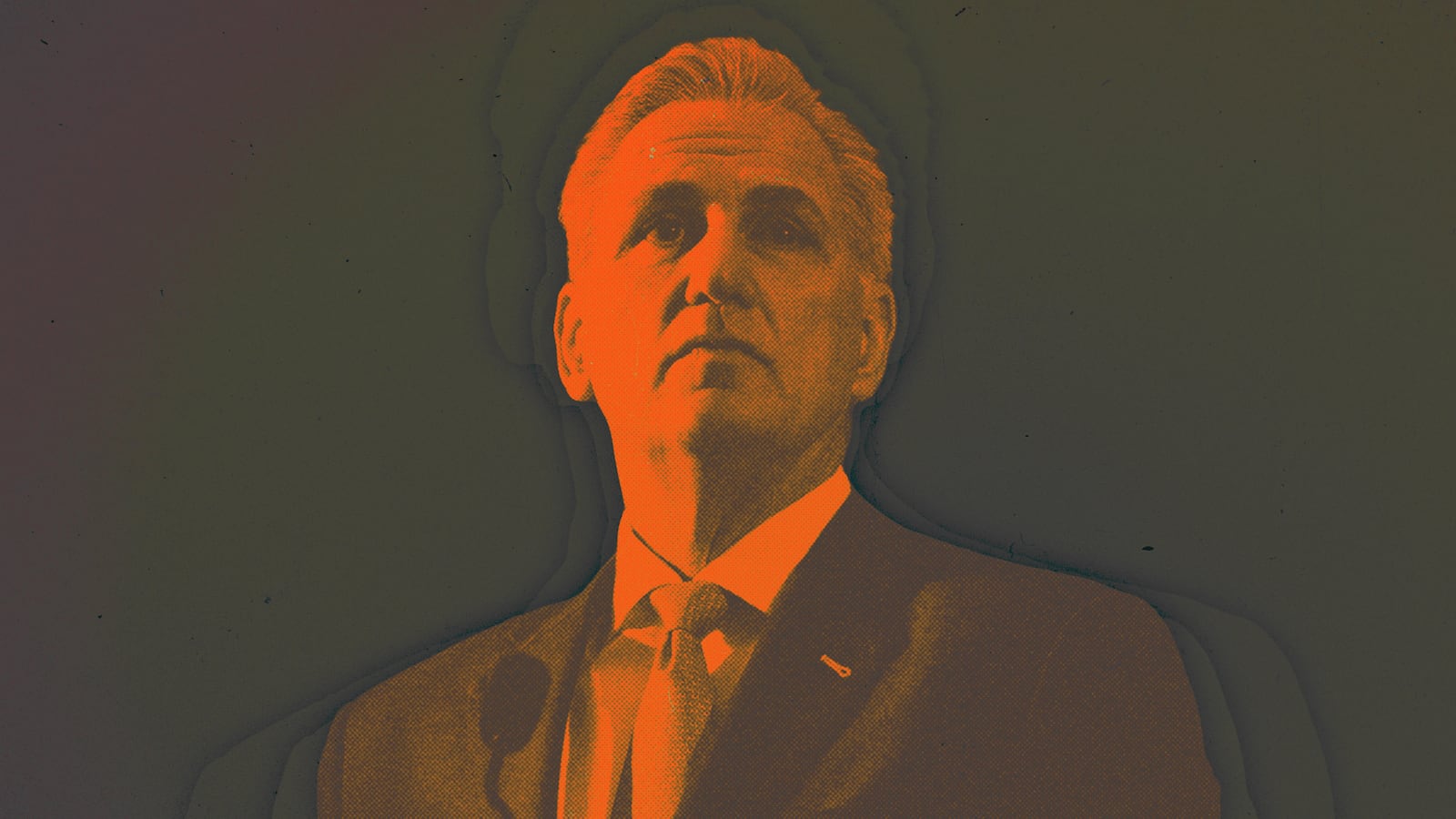

The presentation by the Congressional Budget Office was originally intended just for the Republican conference, but Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) opened it up to Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY) and Democratic lawmakers. The two party leaders aren’t exactly friends, but they have taken steps so far to open up lines of communication across the aisle.

The briefing pleasantly surprised members in both parties. Schweikert, for instance, said some members were “taking shots at each other,” but that he and another Democratic member made similar points on health care spending in front of the audience.

“You only get that,” he said, “when Hakeem and McCarthy put us all in the same room.”

Underneath that outburst of bonhomie, however, is a deeper challenge. In order to tackle some of the most essential issues Congress is facing this term—let alone produce any sort of legislative accomplishment that Republicans could run on next year—McCarthy will need to strike bipartisan deals.

But there are plenty of Republicans who think “bipartisan deals” are exactly the sort of words that may cost Republicans the majority, while other GOP lawmakers think ideological purity at the expense of actual achievements is the recipe for disaster.

“Nothing gets done unless there’s a two-party solution,” said Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick (R-PA), a leader of the GOP’s moderate bloc.

But ask a hardcore conservative like Rep. Ralph Norman (R-SC) if his voters want him to partner with Democrats, and you’ll get a quick answer.

“No,” Norman said. “We’re going in two different directions.”

Polling backs up Norman’s assertions. A Jan. 2023 survey from Pew Research found that just one-third of GOP voters wanted congressional leaders to work with Democrats to accomplish things, even if it disappointed most of the party. Nearly 60 percent of Democrats, meanwhile, said Biden should work with the GOP, even if it disappointed Biden supporters.

The trouble for McCarthy is that he needs both groups of lawmakers—just for different reasons. The Republicans who secured the majority by winning tough races in 2022, and then supported McCarthy through his grueling Speaker race, see it as a top priority to pass bipartisan bills on the toughest issues.

The ones who withheld their support for McCarthy—and won the power to force a vote on his removal at any time—largely don’t.

At least publicly, the Speaker himself has staked out a middle ground. In December, after Republicans won the majority, McCarthy said he can “work with anyone,” but he stressed that the GOP’s victories meant voters wanted “a check and balance” on Democratic rule.

What’s helped McCarthy manage the dilemma so far is that, roughly two months into his tenure as speaker, his bipartisan wins have come not from collaboration with Democrats but through strong-arming them, to the delight of the conservative base.

Just last week, McCarthy celebrated the congressional passage of a House GOP law repealing a number of criminal justice reforms in Washington, D.C.

At first, Biden signaled he was against the bill, and the vast majority of House Democrats voted to oppose it. Then, Biden changed his tune and said he wouldn’t veto it—opening up the floodgates for 36 Senate Democrats and all Republicans to vote for it last week.

McCarthy threw an unusually extravagant signing ceremony before sending the resolution to the president’s desk. Republicans have repeatedly and gleefully tweaked the House Democrats left holding the bag after voting against the crime law repeal. The GOP campaign arm has run attack ads against vulnerable Democrats who voted that way, continuing their midterms push to make crime a problem-area for Democrats.

But McCarthy’s allies don’t think his bipartisan bona fides stop there. They point to up and coming policy—bills moving through committees—as examples that both parties can work together under McCarthy’s leadership.

Rep. Mike Lawler (R-NY), a freshman who flipped a Democratic seat last year, said members are “already working together on a bunch of bills in financial services and foreign affairs.”

“So, I know that I know that the focus is to try and for everybody to try and harp on the negative,” Lawler said. “But I think there’s a lot of opportunity for people to work together.”

Democratic leaders have expressed willingness to work with Republicans on a number of fronts, from countering China to passing the twice-a-decade Farm Bill to reworking the country’s surveillance programs. The two parties came together to enact significant bills in the last two years, like the $1 trillion infrastructure law.

“To my Republican friends,” Biden said last month in his State of the Union address, “if we could work together in the last Congress, there is no reason we can’t work together in this new Congress.”

But no amount of free-wheeling bipartisan exchange on Capitol Hill is likely to dislodge where both parties stand on the most pressing item that requires bipartisan cooperation: extending the federal government’s borrowing authority, known as the debt ceiling. Failing to do so by the time the debt ceiling is reached, projected to be this August, would risk an economically destructive default on the national debt.

Republicans are threatening to vote against raising the debt ceiling—even though it represents past, not future, spending—using the prospect of widespread economic calamity as leverage to force Democrats to agree to unspecified spending cuts.

Democrats, meanwhile, say they won’t entertain hostage-taking on the debt limit and are focused on needling Republicans into detailing their spending cuts.

On this particular front, bipartisanship is not what Republicans want, unless it means Democrats submitting to GOP demands. And Democrats’ posture on the debt ceiling has helped McCarthy manage the two flanks of his conference—for now.

Republicans have been united in attacking Biden’s negotiating stance, a task made easier with Biden’s release of his budget last Thursday. The $7 trillion proposal was treated by Republicans more like a troll than an olive branch.

“The White House and the Senate need to recognize that there’s no longer one-party rule in Washington,” said Lawler. “They have to negotiate with the House in good faith, and I think the President’s budget—which is a month late—is certainly not a good faith effort.”

McCarthy has won plaudits from the varying wings of his conference for his position on the issue so far. “The Speaker’s done well,” said Rep. Ryan Zinke (R-MT). “My understanding is that the Biden administration has not reached out to him—again, it was a promise that they’d work together.”

“I’m hoping that effort happens soon, because the clock’s running,” Zinke said.

But McCarthy’s difficulties are just beginning. Whether Republicans adopt a budget of their own is an open question—as is how McCarthy could possibly write a budget appeasing all corners of his conference when there are so many contradictory goals. Republicans want a budget that balances in 10 years. They want one without cuts to the more than $800 billion Pentagon budget. And, after they were hit over the head for proposals targeting seniors, they want one that doesn’t touch Medicare and Social Security.

And that’s just a messaging document. The budget more closely resembles a glorified press release on Capitol Hill than a binding spending plan. But adopting a blueprint—or not adopting one—could be the start of the problems for McCarthy. The reality is McCarthy’s true test will begin when Republicans have to start agreeing on what cuts, precisely, they will demand from Democrats.

Internally, GOP lawmakers have been circulating various proposals, but the most important marker was thrown down publicly on Friday by the House Freedom Caucus, the hard-right group that was most reluctant to back McCarthy.

The Freedom Caucus said their members would “consider” voting to lift the debt ceiling if Democrats agreed to undo Biden’s student loan forgiveness plan, rescind unspent COVID relief funds, undo Democrats’ marquee climate bill from last year, and cap non-defense spending at 2022 levels for a decade. In short, it’s a complete nonstarter for Democrats.

Rep. Don Beyer (D-VA) said he was optimistic about prospects for working with Republicans—but he questioned what spending could be left for them to cut, since McCarthy has already ruled out touching Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, defense, and veterans’ programs.

“That’s the one place that I’m not optimistic,” said Beyer.

Biden, meanwhile, has similar concerns about the Freedom Caucus proposal. In a brief response Friday morning, he bashed proposed cuts to discretionary spending, which he said don’t match his “values set.”

As negotiations proceed, it does seem that at least one newfound McCarthy ally, who also happens to be a bridge to the far right, is giving him space to work across the aisle.

Speaking on the Capitol steps Thursday, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) gave a sort of kumbaya remark on Democrats and Republicans working together on the debt limit and the budget.

“I’m kind of one of those people I get really sick of both political parties and I continue to say, this institution is supposed to serve the American people, and for us to do that we have to talk to each other,” Greene said.

“So, that’s the way it should be getting done.”