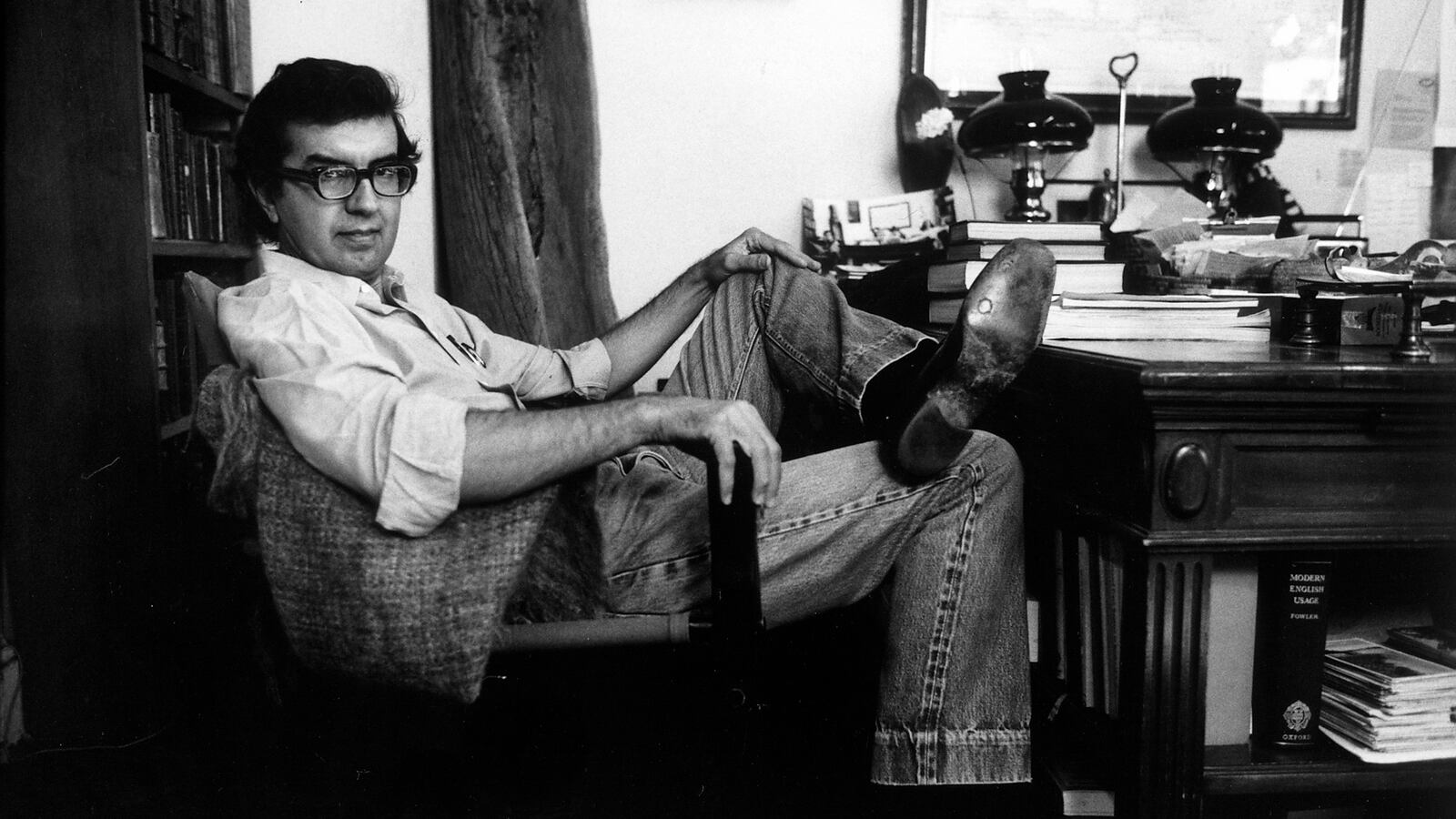

For years, Larry McMurtry wore an old sweatshirt that said “Minor Regional Novelist” on the front. It was a joke but one with more than a grain of truth. Beginning with Horseman, Pass By in 1961, he published a string of tough, unsentimental novels in the ’60s and ’70s about the modern American West and particularly Texas, where he was born in 1936. The novels got good reviews and some of them sold to Hollywood (Hud, The Last Picture Show, Terms of Endearment), but McMurtry did indeed remain a minor regional novelist, albeit one with a small but devoted following.

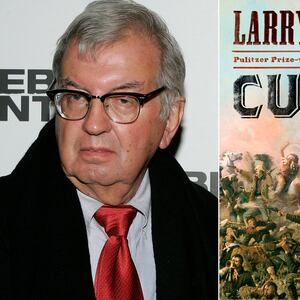

Then in 1985 he published Lonesome Dove, and overnight the minor regional novelist became a Major American Author. His sprawling epic about a 19th century cattle drive from Texas to Montana enchanted not just critics but readers too, selling 300,000 in hardcover and millions more in paperback, and earning McMurtry a Pulitzer Prize. A hugely successful TV miniseries only burnished the book’s success.

Ironically, one of the few people to express reservations about Lonesome Dove’s reception was its iconoclastic author, who in a preface to a new edition in 2000 wrote, “It’s hard to go wrong if one writes at length about the Old West, still the phantom leg of the American psyche. I thought I had written about a harsh time and some pretty harsh people, but, to the public at large, I had produced something nearer to an idealization; instead of a poor man’s Inferno, filled with violence, faithlessness, and betrayal, I had actually delivered a kind of Gone With the Wind of the West, a turnabout I'll be mulling over for a long, long time.” Well, you can’t please everybody.

McMurtry, who died Thursday at the age of 84, liked to joke that after Lonesome Dove, he became two novelists: one the author of highly regarded novels about modern life in the American West that sold respectably, and the other a bestselling writer of cowboy stories.

In truth, the two McMurtrys were never that far apart if you ignored book sales. His stories about outlaws and old Texas Rangers were every bit as well written and closely observed as his novels about Houston astronauts and Vegas showgirls. McMurtry could be hit or miss in the plot department, but his characters are indelible, the sort of indelible that makes you want to reread the books just to renew acquaintance with Aurora Greenway, Duane Moore, and especially Gus McCrae, the aging ex-Texas Ranger who dominates Lonesome Dove (Robert Duvall, who portrayed Gus in the miniseries, said it was the best character he ever played and better than anything that Shakespeare ever came up with).

McMurtry’s protagonists, while invariably flawed, are all likable. McMurtry thought so too, apparently, since he returned several times to write sequels in which he extended the life of someone who interested him. Sometimes the sequels are even better than the originals. Duane’s Depressed, the third time McMurtry would examine the life of Duane Moore, first met as a high school kid in The Last Picture Show, is a ramshackle novel distinguished one of the most nuanced and hilarious portraits of a late 20th century American male ever written. And McMurtry had the rare distinction among contemporary authors of writing equally well about men and women. For every Gus and Duane, there was an Aurora and a Clara.

Critics were rarely unkind to McMurtry, but they sort of took him for granted, especially after Lonesome Dove (how could something so successful be… you know, good?). His fellow writers never made that mistake. “I can’t read McMurtry,” Norman Mailer once said. “He’s too good. If I start reading him, I start writing like him.” The simple truth is, no author has ever captured the American West in all its contradictions better than McMurtry.

In literature and life, McMurtry was a loner (married twice, divorced once) and an inveterate rambler. At various times, he lived in Houston, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, Arizona, and his hometown, Archer City, Texas, which he immortalized (maybe skewered is the better word) in such novels as Horseman, Pass By, and The Last Picture Show, the film version of which was shot in Archer City. And until bypass surgery slowed him up some in the ’90s, he could be found driving cross-country on an almost monthly basis.

Early in his writing career, he took college teaching jobs to pay the bills, as so many writers do, but he was also a renowned antiquarian book dealer. At one point he ran one of the biggest used bookstores in the country, having bought up all the abandoned car dealerships in Archer City and turned them into branches of Booked Up, a store that stocked more than 400,000 titles.

Archer City’s population has never gotten above 2,000 on its busiest day, but it always loomed large in McMurtry’s life. Not only did he set several novels in towns resembling his West Texas birthplace, he seemed to take a kind of grumpy comfort in living there, ensconced in a house that had once been the town’s country club, and which contained more books and DVDs than most libraries, along with a manual Hermes typewriter on the dining room table, Dr. Pepper by the case, and framed photographs of friends as disparate as Susan Sontag and Diane Keaton. There he lived surrounded by the signposts of his past—the unchanging plains stretching for miles (“the prairie the way the buffalo would have seen it,” he told one visitor. “This is the way it looked when my father was born in 1900.”), his grandfather’s house on Idiot Ridge, the ruins of the original last picture show, the Dairy Queen where he hosted visitors for biscuits and gravy. His friend Sontag said he lived inside his own theme park.

Although never exactly a Hollywood darling, McMurtry thrived there as a screenplay writer and script doctor, a second career that culminated in the 2006 Oscar for Brokeback Mountain’s screenplay, which he co-wrote with his frequent collaborator Diana Ossana.

McMurtry was always prolific (even after his heart surgery, when he slid into a deep depression, he managed to write Streets of Laredo, one of his best books), but in the last third of his life, he pushed the accelerator to the floor and kept it there. Between 1995 and his death, he wrote 14 novels, several screenplays, and a dozen books of nonfiction on a range of subjects (the history of the West, Native Americans, driving around America, the ins and outs of Hollywood). A few of these books read like they were written on autopilot, but a couple of the nonfiction books were exceptional, as good as any fiction he ever wrote. Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen is one of the most evocative books ever written about growing up lonely in a cultural desert. A book that gives equal weight to the German essayist of the title and the life of modern cowboys, “It’s really a book about what kinds of memories you can have in a place where nothing happens,” he once told an interviewer.

So call him the lariat laureate of wide-open spaces where nothing happens. In his splendid biography of Crazy Horse, he writes, “He lived his life under one of the most generous skies in the world... such skies, hovering over the rolling land, with the horizons a mystery, with mirages frequent, make the plains a place that calls forth imaginings.” He could have been writing about himself, for surely few writers have been more inspired by a stretch of geography and the people on it, and fewer still have so beautifully caught the landscape or its inhabitants and delivered them, alive and kicking, to the page.