The U.S. Marine Corps is around six years away from putting a laser cannon on its trucks, according to one top general.

The goal: to outfit ground forces with a weapon that can shoot down enemy aircraft faster and more precisely—and at lower cost—than today’s guns and surface-to-air missiles.

The Marines need the laser cannon to defend themselves against increasingly sophisticated Russian and Chinese forces in the event of a full-scale war, Lt. Gen. Robert Walsh, one of the Marines’ deputy commandants, said at an arms-industry conference in Washington, D.C., on June 23.

“When we see near-peer competitors, the development that’s going on in Russia and China, it is really waking us up to what we’re going to have to do in the future,” Walsh said, according to USNI News, a trade publication.

Walsh said the Marines’ current air-defense weapons—primarily old Humvee trucks fitted with a .50-caliber machine gun and Stinger short-range surface-to-air missiles—aren’t up to the difficult job of shooting down fast-moving Russian and Chinese planes, particularly small, stealthy drones.

These missile- and gun-armed Humvees, dubbed “Avengers,” date back to the early 1990s. The trucks are slow, and their missiles and guns take too long to aim. In the early years of the Iraq War, the Army stripped the missiles from its own Avengers and deployed them as machine gun-hauling convoy escorts, protecting cargo trucks from insurgent ambushers.

“So we look at our air-defense capability as certainly a weak area that we have not upgraded in a long time because we haven’t had to deal with that in the operating environment we’ve been in,” Walsh said.

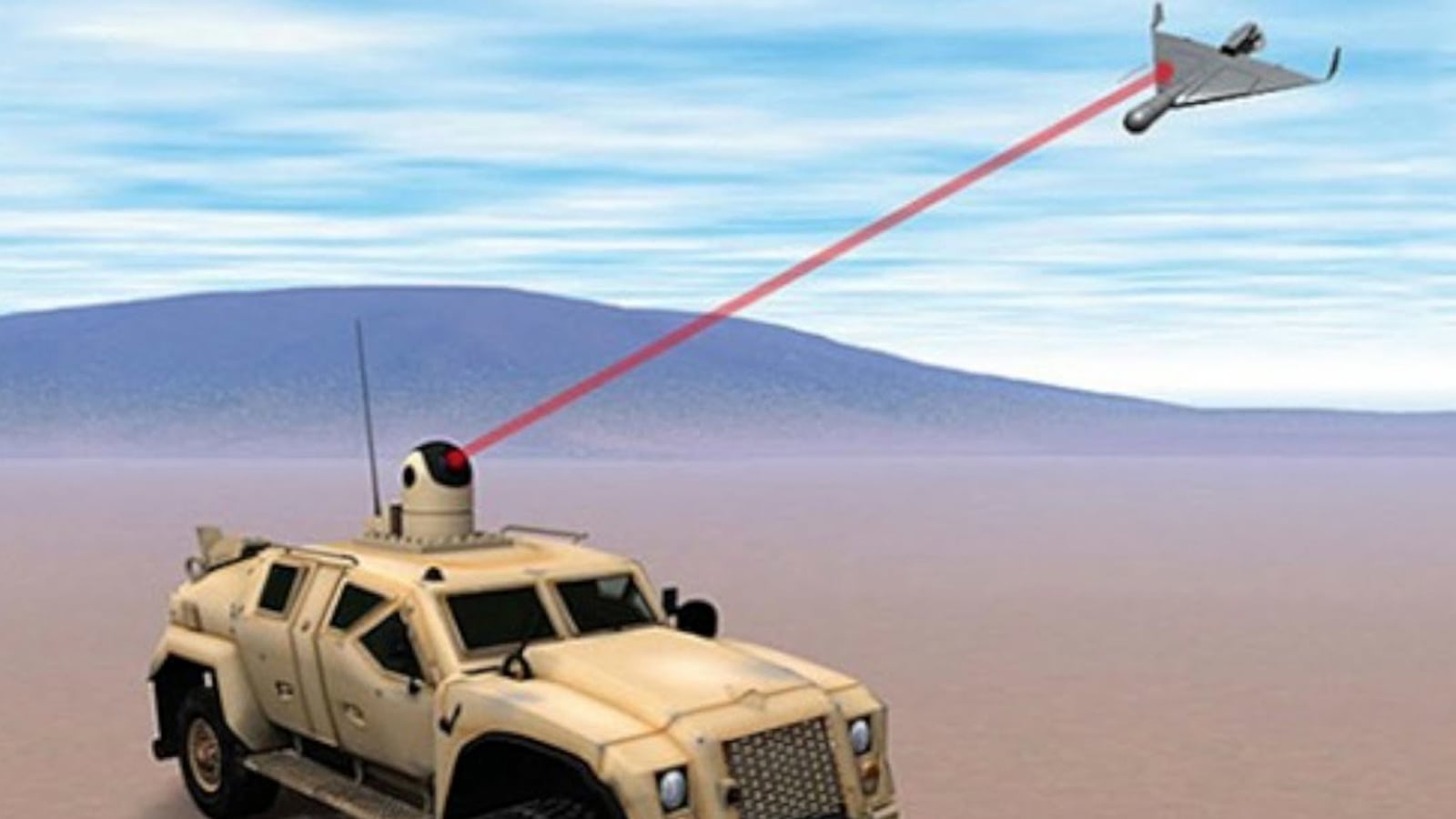

The Marines could outfit their new Joint Light Tactical Vehicle—a high-tech armored truck that’s in development to replace the Humvee—with the laser sometime after 2022, the year the Office of Naval Research is scheduled to finish developing the Marines’ main laser gun.

Known by the somewhat unwieldy official name “Ground-Based Air Defense Directed Energy On-the-Move,” or GBAD OTM, the 30-kilowatt-hour laser system includes a beam director—the “cannon” part of the weapon—cooling hardware and lithium-ion batteries for power-storage, altogether small and light enough to “conform to the size, weight and power constraints of using a tactical vehicle platform,” according to a Navy fact sheet.

The Navy envisions the laser truck traveling with two other trucks—one to carry a radar and another to haul the computerized control system that links the radar to the laser. The three trucks and their crews would detect, track, and destroy targets as a team.

In theory, a computer-aimed laser is potentially much cheaper, more responsive, and more accurate than an old-school surface-to-air missile. An Avenger can fire no more than eight Stingers and 200 machine gun rounds before needing to re-arm. And those eight Stingers cost around $40,000 apiece.

By contrast, a laser cannon can fire potentially hundreds of times out to a distance of a few miles, each blast lasting a few seconds—long enough to burn and explode a small drone. Each shot of a tactical laser such as the GBAD OTM costs a dollar or so, “the cost of the fuel needed to generate the electricity used in the shot,” Ronald O’Rourke, a weapons expert with the Congressional Research Service, explained in a recent report.

The Navy, which oversees most of the Marines’ big technology programs, began tinkering with the GBAD OTM in 2015 and expects to conduct a realistic test of the laser cannon—shooting down a target drone while on the move—in 2022. Walsh said the Marines should hurry to buy the laser truck after that test, assuming it’s successful.

Early on, the laser trucks would patrol side-by-side with old Avengers, Walsh said. “Eventually, if you could transition away from the missiles to go directed energy-only, we would do that,” he added. But the Marines would probably need a much more powerful laser in order to fully replace traditional missiles.

But there’s reason to be optimistic. The military has been working on laser weapons for decades. And after several high-profile setbacks with expensive, volatile, chemically fueled laser guns, Pentagon scientists have settled on chemical-free, “solid-state” lasers.

The three that show the most promise, according to the House Armed Services Committee, are the Navy’s ship-mounted defensive laser, currently undergoing sea trials in the Persian Gulf; the Army’s truck-mounted anti-artillery laser; and the Marines’ own, smaller truck laser.

“Each of these programs demonstrated the increased power output and power on target necessary to develop a militarily useful directed-energy weapon,” the committee reported.

Walsh said the Marines also would like to eventually fit a laser cannon similar to the GBAD OTM to its aircraft, too—especially its Harvest Hawk gunships, which are lumbering C-130 transports fitted with missiles and sophisticated sensors.

If the laser cannon’s development stays on track, it might not be long before the Marines are capable of firing lasers from the ground and the air, blasting enemy drones at the speed of light.