Last Call: When a Serial Killer Stalked Queer New York is yet another disturbing true-crime documentary about a fiend preying upon a marginalized community. However, the compelling hook of Anthony Caronna and Howard Gertler’s four-part HBO investigation (July 9) is that it’s both a whodunit and a sociological critique of the era and environment in which its tale took place: early 1990s New York City, whose climate of homophobia facilitated its villain’s homicides. With anti-gay and trans legislation currently sweeping the nation, it’s an all-too-relevant story about persecution and violence, and the way in which public rhetoric—and inaction—fosters further hate.

Director Caronna’s series begins with the 1992 discovery by maintenance workers of a dismembered body in Burlington County, New Jersey. Cut into seven pieces, each of them wrapped in newspaper (and a shower curtain) and packed into different trash bags, this individual was—via his briefcase and personal belongings—swiftly identified as Thomas Mulcahy, a 57-year-old husband and father who was in the area for a business meeting. Detectives also found latex gloves, a compass saw, and a linen sheet in the plastic bags, one of which was eventually traced back to Staten Island’s lone CVS. Otherwise, however, there was little useful physical evidence procured from these items, so cops shifted their attention to Mulcahy’s movements in the days and hours leading up to his murder.

As they soon learned, Mulcahy had last been seen on July 8, 1992, at midtown Manhattan’s Townhouse Bar, an upscale gay watering hole where older well-to-do gentlemen often met younger suitors. Douglas Gibson remembers talking to Mulcahy that evening and spying an unknown man in his vicinity, but he didn’t get a good enough look at this stranger to provide an actual description. Cops, meanwhile, found it difficult to convince people in and around this establishment to talk to them, since in 1992, the relationship between the police and the gay community was defined by distrust, if not outright antipathy, much of it born from the former’s history of prejudiced harassment and hostility. If that proved a significant hurdle in the case, so too was law enforcement’s still-lacking interdepartmental communications, and it was this failure that delayed their realization that Mulcahy’s murder was part of a ghastly pattern.

A year earlier in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, the similarly dismembered body of Peter Anderson had been found. Like Mulcahy, Anderson was a closeted gay man, and on the night of his disappearance on May 5, 1991, he too had visited The Townhouse. When investigators into Mulcahy’s slaying heard about this, they knew the two murders were linked. Worse, they were followed by the nearly identical murders of 44-year-old prostitute Anthony Marrero (in May 1993) and of 55-year-old Greenwich Village resident Michael Sakara (in July 1993), the latter of whom was a regular and well-known staple at the Five Oaks bar. Clearly, someone was killing gay men after meeting them at clubs, and because of his modus operandi, the assailant was dubbed by The New York Daily News as the “Last Call Killer.”

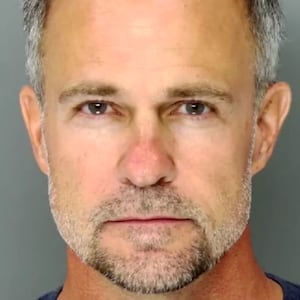

Still from Last Call: When a Serial Killer Stalked Queer New York

HBOLast Call is, on the one hand, a traditional suspenseful mystery, with various police officers discussing their efforts to piece together clues and understand their victims’ backstories in order to locate a suspect. Just as captivating, though, it’s a vivid snapshot of its particular moment, narrated in large part by two individuals who were on the frontlines of the fight for equal LGTBQ+ rights: The New York Gay & Lesbian Anti-Violence Project’s Bea Hanson and Matt Foreman. Recalling a time when gay Americans were both emerging from the shadows in force (especially in NYC) and facing increased antagonism and threats (including from the raging AIDS epidemic), Hanson and Foreman offer intimate and passionate first-hand accounts of the cultural and political atmosphere of the early ’90s. In doing so, they help contextualize these murders as an outgrowth of the long-standing brutality that gay (and trans) men and women faced on a daily basis.

Employing plentiful archival material, Last Call is a simultaneously vibrant and sorrowful look backwards, its nostalgia for the burgeoning gay movement colored by the fear that so many felt because of homophobia and the mortal danger it posed—as well as the anger that was a direct byproduct of being ignored, slandered, and oppressed. Director Caronna’s series honestly and compassionately revisits the past, putting a nuanced face on people who were so often dismissed, discarded, and reduced to unflattering stereotypes, including Mulcahy, Anderson, Marrero, and Sakara. Featuring interviews with friends, lovers, and relatives of the four men whose lives were horrifically cut short by a madman, it remembers—and celebrates—them not as statistics, but as flesh-and-blood individuals.

Still from Last Call: When a Serial Killer Stalked Queer New York

HBOIn separate interviews with different detectives, Last Call highlights police officers’ ignorance about the gay community and their reticence to relate it to these murders. Such blindness, whether willful or not, feels at least somewhat connected to the series’ own deliberate dismissal of the fact that the killer—who, through modern fingerprint analysis, was identified as Mount Sinai nurse Richard Rogers Jr.—was also a gay man. There’s a persistent sense, from all angles, that intolerance (and fear of vilification) has repeatedly frustrated attempts to solve, and comprehend, this tragedy, and the fact that Rogers never opened up about his motivations only further leaves things feeling depressingly murky.

What remains clear, though, is Rogers’ guilt. Having been previously acquitted of killing his college roommate and, years later, of assaulting another man, the quiet and soft-spoken medical professional was undoubtedly the serial culprit authorities had sought. No matter the questions about jurisdiction that arose at trial, he was justly sentenced to two consecutive life sentences, ending a reign of terror that—due to his habit of taking routine trips around the country—may have included many more unknown victims. He was, by all accounts, a monster seemingly without remorse, and Last Call is sharpest when it posits him as the result of a society that demonizes with malicious intent (be it Anita Bryant in the ’70s or Ron DeSantis today) and, in the process, inspires inevitable cruelty.