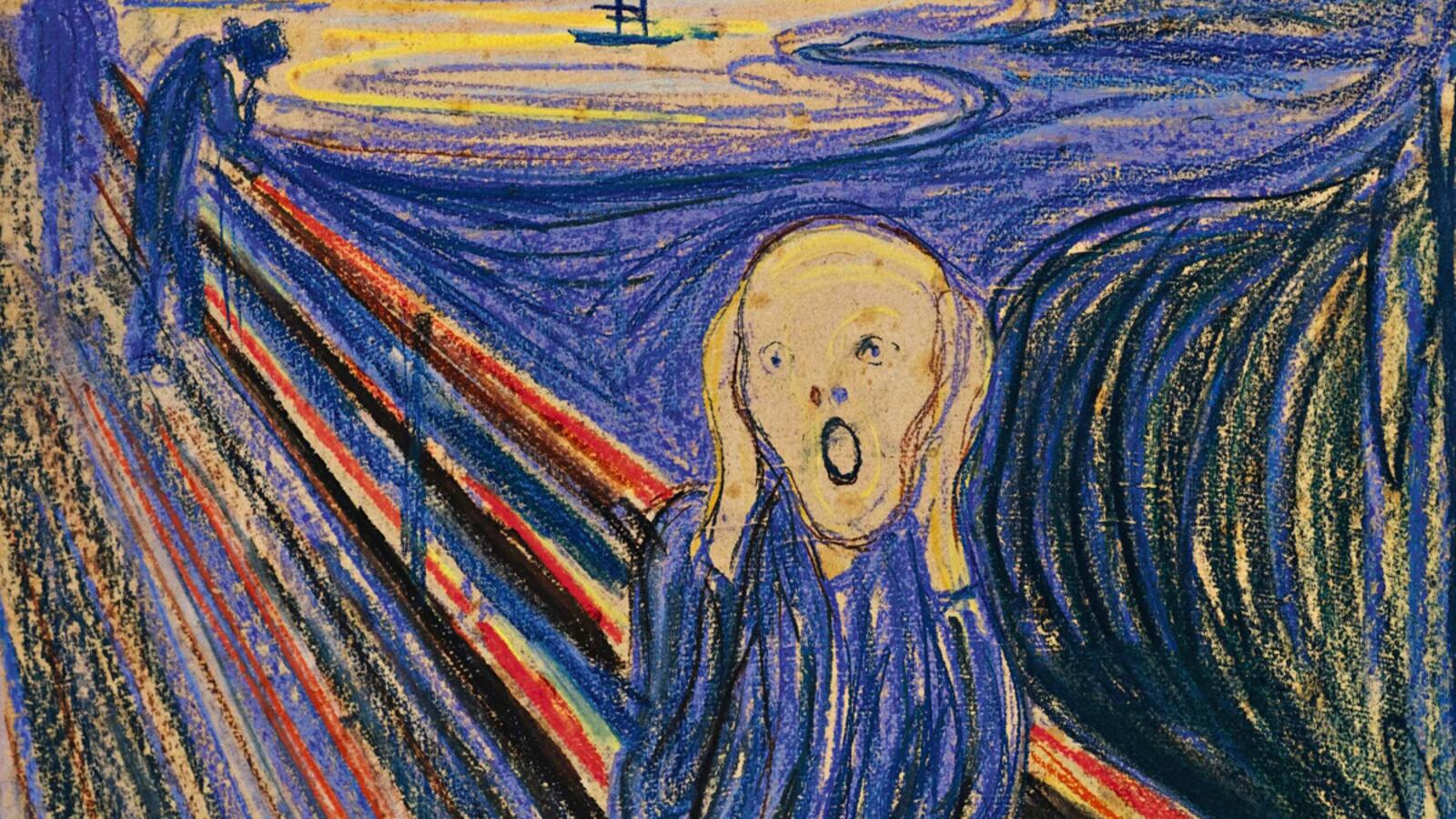

On Wednesday night at Sotheby’s in New York, when an anonymous buyer offered 119.9 million for Edvard Munch’s “The Scream,” it became the most expensive artwork ever sold at auction. (But still fetched less than half the record $250 million reported to have been paid for a Cézanne last year, in a private purchase by the state of Qatar.) The obvious question now is whether the picture was worth it—not as an investment, not for bragging rights, but in terms of real artistic value.

It seems maybe it wasn’t, at least if you believe the well-heeled crowd that gathered Tuesday evening for a first and probably final chance to take in the picture, before its disappearance into some billionaire’s vault. In the measly half hour that I spent drinking in this “masterpiece” at close quarters, almost no one joined me for more than a minute or two, and most spent less than 10 seconds. “There’s only maybe five people all night who’ve really stood and looked at it,” said one of the many security guards in attendance. “They should be honored to see such a thing.” It seems the picture didn’t have that kind of pull.

Three girls in black sheaths and stilettos came up for a quick glance. “It’s really exciting,” said one, in the tone you’d use to order a bagel, then wandered off again with her friends.

“Who’s the painter—tell me?” demanded a lightly addled matron who’d sidled up for a moment. “I don’t like the face.” Her younger companion, wearing pearls the size of the quail eggs that Sotheby’s was serving, took a quick glance and disagreed: “It’s very beautiful,” she said, in art’s autopilot response. Beautiful? The essays in Sotheby’s own catalog insist that when the picture was made, in 1895, it was all about a deliberate and revolutionary embrace of ugliness and angst. (Disclosure: A sibling of mine wrote one of those essays.)

But maybe that pearl-wearer’s cliché was perversely correct: the ugly truth that this picture started out telling has, thanks to Sotheby’s, been alchemically transmuted to the beauty of a nine-figure bid—the first in auction-house history.

Numbers also help explain all that inattention on Tuesday night. Money doesn’t have to be studied to be appreciated. A quick glance—a sniff—is all it takes to acknowledge a wad. I saw far more people grinning at the preciousness now wrapped around Munch’s picture than frowning at the sadness the artist put into it. Early on, one version of “The Scream” was defaced with the words, “Could only have been painted by a madman.” But an artist who could dream up a picture worth as much as a yacht doesn’t seem to scare us a bit.

Beyond the easy distraction of price, there may be another reason that no one at the preview was giving the picture too much of their time. It may not require it. “The Scream” may be the original and greatest of artistic one-liners—source of the one-liners that have become art’s staple diet. Munch’s picture expresses modern angst in a perfect, tidy package, and has nothing more to do once that’s done. (In a speech after the auction, the wealthy Norwegian who sold the picture tried reading it as showing “the horrifying moment when man realizes his impact on nature and the irreversible changes that he has initiated, making the planet increasingly uninhabitable.” Let’s just say that doesn’t work as well as the old chestnut that has Munch screaming about psychic alienation.)

I have to admit that my 30 minutes with the picture pretty much squeezed it of juice, compared to the hours that I’ve spent with single pictures by Titian and Velazquez and Cezanne (even by Jeff Wall and Gerhard Richter) without feeling that I’ve done them justice. The very best pictures by those artists seem impossibly complex and multilayered, defying paraphrase. Whereas “The Scream” seems to have become famous and iconic precisely because it speaks so directly and simply. That’s why it has survived so much reproduction. Munch himself did four full-scale versions of it and many more reductions as prints, and since he died its image has gone viral without falling sick. “The Scream” may be one case where fame and popularity may point to the weakness in an artwork, as much as to its strength—or if not quite to weakness, at least to a very narrow range of success.

Other great artists have dug deep into the nature of art and vision and society, and it shows in almost every work they made. With Munch, “The Scream” makes a statement that seems to stand almost alone, as a freestanding achievement barely bolstered by others. On Tuesday at Sotheby’s, one whole wall was filled with scream-free Munchs that were also on offer. No one stood near them except three guys with their backs turned, discussing houses for sale in the Hamptons—at prices higher than some of those Munchs went on to fetch at the sale.

At the tail end of Tuesday’s preview, I went back for one last look at “The Scream.” By the time I got close, I was truly alone. The night’s remaining crowd was keeping to the far side of the stanchions, where you didn’t have to surrender your drink. With minutes left to study one of the most famous pictures, ever, Chardonnay time was winning out over “Scream” time.

Looking back at the work, it was easy to believe that its screamer was the artist himself, outraged at what he’s become.