Lawrence Ferlinghetti, the innovative bookseller and publisher of Ginsberg and Kerouac, one of the best friends free speech ever had, and the man who wrote that most anomalous thing—a poetry bestseller: A Coney Island of the Mind—died today at the age of 101.

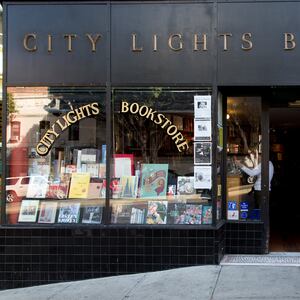

“If amendments had addresses, the address of the First Amendment would be right here at City Lights Books,” said historian Kevin Starr, standing outside Ferlinghetti’s legendary San Francisco bookstore at its 50th Anniversary in 2003 (City Lights was also the name of the poet’s equally celebrated publishing company). “You will never see the First Amendment so fully and so happily ensconced as it is here. Lawrence Ferlinghetti, congratulations. Literature, Culture, the First Amendment is better because of you.”

A brave bookseller, an innovative publisher, and an author who introduced several generations of readers to the idea that reading poetry could be more fun than work, Lawrence Ferlinghetti was born on March 24, 1919, in Yonkers, N.Y. Shortly before his birth, his father died of a heart attack, and his mother, in the midst of a nervous breakdown, was institutionalized. So, when he was one week old, his aunt Emily took him to France.

Lawrence Fierling, as he was called before he returned his name to its original, grew up thinking he was French, and throughout his life, he carried a bistro-civil libertarian socialist point of view. Aunt Emily and Ferlinghetti left France for America when he was about six. Too poor to raise him, she sent him to an orphanage for about a year, until she eventually found work as a teacher with a wealthy family in Bronxville. But then Emily up and left again. No word. No reason. Just gone, back to France without the boy who up to that point believed she was his mother. When he turned 12, he reconnected with her and for a while, they corresponded in French, at which point, he later said, he knew he was a writer. But then Emily disappeared and this time for good, vanishing without a trace, and was never heard from again, by anyone.

Ferlinghetti’s life is best told through his poetry. He traces his father’s route to America at the turn of the century. (He even returned to Italy to see where his father was born and was arrested when he tried to get a look inside.) The story of his mother and father’s meeting at Coney Island is beautiful. Yet, how would he know? Who would have told him? That’s sort of the beautiful part. He’s emotional about the parents he didn’t know.

He lived with the wealthy family in Bronxville as an unofficially adopted son. Their own son, also named Lawrence, had died as an infant, and Ferlinghetti was well cared for by the couple. A great library with massive volumes collected by his adoptive father surrounded him. For every poem he recited at dinner, his father gave him a silver dollar. He was an Eagle Scout but got kicked out of public school for stealing pencils at a dime store and then was shipped off to boarding school. There he learned about Thomas Wolfe and was enamored enough to follow Wolfe’s footsteps to the University of North Carolina, where, like Wolfe, he tried—unsuccessfully, as it turned out—to write for Carolina magazine.

After Chapel Hill, Ferlinghetti enlisted in the Navy. On D-Day, he was aboard the smallest ship in the armada, from which he watched, offshore, as the troops storming the Normandy beaches were shot by the Germans.

An interviewer once asked how he survived World War II. “I was lucky,” he said. “I had a guardian angel watching over me, because I was in the Normandy invasion, there were bombs dropping all around me, and nothing hit me. So I think it was a guardian angel watching over me.”

With a Zelig-like ability to be seemingly everywhere, he was later transferred to the Pacific Theater and turned up at Nagasaki six weeks after the second atomic bomb was dropped. When he arrived the city was a ghost town—no Japanese army, no one guarding the city, which by then was nothing more than a pulp of ruins, flesh and bone fused to wood and steel and grass and dirt. “Made me an instant pacifist,” he said years later. “No doubt about it.”

After leaving the navy, he went to work in the mailroom at Time Magazine, still hoping to become a writer, but he quickly became disillusioned with the news business. He bounced from Time to Columbia University on the GI Bill and received his M.A., then returned to Paris, where he did his doctoral work at the Sorbonne, and, perhaps more important, met George Whitman, who would become a lifelong friend and whose dream of opening a bookstore inspired the same desire in Ferlinghetti. Whitman soon opened Shakespeare & Co., inspired by the bookstore of the same name run by Sylvia Beach that had shuttered at the beginning of World War II. Ferlinghetti returned to America and settled in San Francisco, where, in 1953, he opened his own bookstore, City Lights, which housed his own publishing company as well.

At soirees held by the poet Kenneth Rexroth in his home in San Francisco’s Fillmore District, Ferlinghetti became more politically engaged. Rexroth had a KPFA radio talk show with an extremely flexible format that allowed him to talk about the classics, philosophy, politics, astronomy—you name it, Rexroth would talk about it. Ferlinghetti would eventually publish Rexroth’s work, but at that point, he was content to be among the small group of writers milling around the better-known poet and political anarchist. They were just getting started with the poetry-set-to-jazz thing. They were just learning about the marriage of visual art and poetry. They weren’t called Beat Poets yet, but it wouldn’t be long.

Soon thereafter, Ferlinghetti also effected a radical change in publishing. There was at that point no such thing as a quality paperback. But Ferlinghetti’s friend Peter D. Martin was publishing a literary magazine called City Lights, and Ferlinghetti had the notion of adapting the magazine’s design for the books he wanted to publish: paperbacks, yes, but printed on good stock, with well-designed covers, and often formatted to fit easily in a back pocket or a handbag. And so, with a handshake and $500 each from Ferlinghetti and Martin, City Lights was born.

Beat poets were certainly among the best-known poets that City Lights, both publisher and book store, sold at first. But, as Ferlinghetti would spend the rest of his life reminding people in interviews, “the beats were only one generation of dissident writers that we published at City Lights.” His nutshell mission statement: “Our focus is on radical politics, radical deep ecology, feminism, and poetry.” From the beat poetry that put Ferlinghetti and City Lights out front, the publishing house moved into novels and translations. City Lights was a vehicle to publish himself first—Pictures of the Gone World (Pocket Poets #1)—and thereafter he cast a wide and eclectic net: William S. Burroughs, Noam Chomsky, Charles Bukowski, Jack Kerouac, Howard Zinn, Ralph Nader, Lisa Gray-Garcia aka Tiny, Amy Scholder, Rebecca Brown, and even Ry Cooder. The press still thrives, and so does the bookstore.

Pocket Poet series #4 nearly derailed everything, though.

Allen Ginsberg said he “first read Howl at a small gallery performance space where all of us as a poetic group all got together on the same stage with Kerouac in the audience and with Neil Cassady in the audience.”

It was October 7, 1956. Ginsberg read, and so did Philip Lamantia, Gary Snyder, and several others. It was mostly poets reading their work to other poets and writers that night. But Ferlinghetti was also there at 6 Gallery on Fillmore Street, and he wasted no time in sending Ginsberg a telegram that echoed Ralph Waldo Emerson’s famously encouraging note to young Walt Whitman (“I greet you at the beginning of a career.”) and then followed that up with the query sent by every eager publisher since books were invented (“When do we get the manuscript?”).

And just like that, Howl was published.

If Ginsberg had little trouble getting Howl into print, his publisher Ferlinghetti had a very rough time once the book came out.

“Now, as you may have seen in the papers, Collector of Customs Chester MacPhee confiscated 520 copies of a paperbound volume of poetry entitled Howl and Other Poems by Allen Ginsberg... You wouldn’t want your children to come across it,” said Kenneth Rexroth on KPFA in 1956 just after the confiscation of the books, which had been printed in London and shipped to the United States.

The manager of City Lights Bookstore, Shig Murao, was arrested for selling the book to a police officer at the shop. Ferlinghetti wasn’t present, so a warrant was issued, and when he turned himself in, the 38-year-old publisher was charged with selling obscene books.

When the case came to court, Ferlinghetti faced a possible six-month jail sentence as well as the possibility of losing his bookstore and his publishing company. For his defense, he had three attorneys from the ACLU, nine witnesses, and a favorable New York Times book review. The judge hearing the case was a conservative Christian.

As it turned out, Judge Clayton W. Horn was also a thoughtful man. In ruling for the defense in the case of People of the State of California v. Lawrence Ferlinghetti (1957), Judge Horn wrote, “The best method of censorship is by the people as self-guardians of public opinion and not by government. So we come back, once more, to Jefferson's advice that the only completely democratic way to control publications which arouse mere thoughts or feelings is through non-governmental censorship by public opinion.” Howl was ruled not obscene because it had social value. Or, as Horn put it, “In considering material claimed to be obscene it is well to remember the motto: 'Honi soit qui mal y pense.'" (Evil to him who evil thinks.)

After the verdict, Ferlinghetti was a generous victor: “The San Francisco Collector of Customs deserves a word of thanks for seizing Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems and thereby rendering it famous. Perhaps we could have a medal made. It would have taken years for critics to accomplish what the good collector did in a day, merely by calling the book obscene.”

In the documentary Ferlinghetti: A Rebirth of Wonder, novelist Herbert Gold commented, “Lawrence Ferlinghetti kicked open the door to free up publishing at a time when it really needed to happen. He risked a great deal for a lot of books that couldn’t have been published in this country. Many books that are now considered classics can now be freely read, carried in your back pocket, and taught in almost every university in the country.”

Ferlinghetti knew how to make a stir and take a stand as a publisher, but as an editor, he also knew how to coax a book out of a writer, even if it took years. Frank O’Hara’s classic Lunch Poems was a much quieter process than Howl. It happened in postcards. And with a lot of patience. There’s romance in that. It took only one of O’Hara’s poems to prompt Ferlinghetti to write to him. The correspondence read: “How about a book of Lunch poems.” O’Hara returned a postcard with one word, “Yes.” But then nothing happened. So, Ferlinghetti sent another postcard: “How about lunch?” O’Hara responded, “It’s cooking.” It took a few years but eventually, in 1964, City Lights published the durably delightful Lunch Poems as number 19 in the Pocket Poets series.

At the age of 95, Ferlinghetti published Poetry as Insurgent Art, a book that he said, “sums up what I’ve always considered the role of the poet—poetry should be dissident and subversive and an agent for change.”

He continued writing, publishing, and holding readings almost to the very end of his long life, and even published a novel on the eve of his 100th birthday.

And the upper floor windows of City Lights were always covered in handwritten signs. He called it his blog. There, he broadcast his views on change—an optimistic leftie until the end, always speaking up in support of community and free thought.

The secret of life, he left for us: “Tenderness, live with tenderness.”