The young lieutenant who had recently arrived in the Intelligence Department in Cairo did not impress. “He was an extremely youthful and, to our unseeing eyes, insignificant figure,“ recalled a more senior officer later, “with well-ruffled light hair, solitary pip on sleeve, minus belt, with peaked cap askew.”

It’s exactly a hundred years ago that T. E. Lawrence joined that small group of spooks. Today the world is still debating the consequences of the ideas, adventures and influence of that rather scruffy officer. There was a breathtaking arrogance to the world view of his British commanders who had taken charge of Egypt, pronouncing it to be under their “protection” in their recently-declared war against the Ottoman Empire and their German allies.

Lawrence wasn’t familiar to most of his colleagues; the few who knew him thought he was ill-suited to be in any army. By habit he was a loner, but he was a brilliant specialist in a field that had suddenly become of vital military importance, the tribes of Arabia. That kind of knowledge made him the perfect tool for the mission in hand: overriding indigenous cultures and movements for political independence in order to “make the world safer” for western interests.

In Europe the war was already slipping into a pattern of static confrontation between large armies with seemingly no strategy except mutual annihilation. In the Middle East nobody quite knew where a front line might be – the British and the French were plotting revolt and sedition in the vast Ottoman lands because they were not yet ready to mount a major conventional war.

It turned out that as gifted as he was as an intelligence officer T.E. Lawrence was a genius when it came to fomenting revolt. His knowledge of the Arab desert tribes and his understanding of the terrain enabled him to demonstrate the impotence of a large, well-equipped army when faced with a small, highly mobile force fired up with the promise of liberation from colonial rule. Within two years of arriving in Cairo, Lawrence was becoming a cult figure among the desert Arabs, with exploits real and embroidered that would later make him one of the most famous men on earth, as Lawrence of Arabia.

However, as the Ottoman Turkish armies broke up in disarray and retreated from their desert outposts there was a problem: those promises of liberation from colonial rule – and how to make good on them.

While Lawrence was still desk-bound in Cairo he and his fellow officers were trying to plot what a post-Ottoman Middle East might look like – bearing in mind that to the British the single most important thing was that it should not interfere in any way with the security of their empire – particularly access to the Suez Canal and other routes to India. There was also a new concern: oil. The Royal Navy’s battleships were converting from coal to oil-fueled power, and the Middle East’s first oil fields were in the Persian Gulf.

At the heart of British designs for the region was Syria – not Syria as we know it today but a greater Syria united with Egypt including Palestine and the Sinai under a titular Sultan – in fact, a sprawling new Caliphate under British “protection” – the favorite euphemism for domination.

Lawrence was accepted as the office specialist on Syria. He wrote a long paper that displayed his knowledge of the cultural, racial, tribal and religious diversity of the lands that would constitute such an entity, giving vivid sketches of the Syrian cities of Homs, Hamah, Aleppo and Damascus – “Damascus is the old inevitable head of Syria” he wrote.

Having made very clear that, in truth, there was no naturally homogenous foundation for a Caliphate Lawrence concluded that they had to invent one: “…the only imposed government that will find, in Moslem Syria, any really prepared groundwork or large body of adherents is a Sunni one, speaking Arabic, and pretending to revive the Abbassides or Ayubides” – references to the great Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad and the Sultanate established in Damascus after Saladin’s famous conquest of Syria.

There was no mention of France in this plan for a British “protectorate” that would dominate the most strategically critical region of the Middle East. Eventually the British would have to concede French claims to a chunk of the Ottoman Empire.

On October 1, 1918, Lawrence entered Damascus with an Arab army loyal to Feisal, an Arab prince of the Hashemite tribe. British commanders in Cairo consented to this display of an Arab “freedom force” but had no intention of allowing them to rule Syria. As Lawrence wrote later: “…the old men came out again and took our victory to re-make in the likeness of the former world they knew.”

Like so many parts of the Lawrence story, or myth, this is disingenuous. Lawrence was a virulent Francophobe and certainly didn’t want Damascus to go to the French, but his idea for its future was still consistent with his original Cairo document. “The Arabs,” he wrote some time later, “should be our first brown dominion, and not our last brown colony.” (The distinction between a dominion and a colony suggested handing over more political independence to the Arabs than Lawrence’s masters in London ever intended and his use of “brown” was an inference that the days of white supremacy might be over – another over-optimistic belief on his part.)

At the end of David Lean’s masterly epic version of the myth, Lawrence of Arabia, the 30-year-old Lawrence leaves Damascus looking broken, physically and spiritually. This was not at all the case. Lawrence saw that he had a second campaign to wage – in smoke-filled rooms as a political player in “The Great Game” that would remake the Middle East. And already he instinctively sensed his own star quality and how to use his celebrity for political ends.

A year after leaving Damascus Lawrence was at the Paris Peace Conference lobbying hard to get the 33-year-old Prince Feisal on a throne in Damascus. The alliance of Lawrence and Feisal dismayed British diplomats, one of whom wrote “I consider the further cooperation between these two in Paris is likely to cause us serious embarrassment with the French.” (Their closeness in age was lost in Lawrence of Arabia because a much older Alec Guinness played Feisal against Peter O’Toole’s golden youth as Lawrence; in Paris together they both had the potent charisma of a new generation.)

In fact, nobody seemed to know on whose authority Lawrence was appearing in Paris. Four British government departments – the War Office, the Foreign Office, the Colonial Office and the India Office – all tried for months to agree which of them actually employed him. In the end he was attached to the conference as a “technical adviser.”

That did little to control Lawrence. One diplomat, more a cynic than a realist, advised that Lawrence would be useful to British interests “if properly handled” to which another responded: “The trouble is that it is always Colonel Lawrence who does the handling.” His British superiors rapidly concluded that in Paris Lawrence was a dangerous man – as dangerous to them as he had been to the Ottomans.

The British and the French claimed to be creating a new world order when, in reality, they wanted the old world order but without the Ottomans.

Lawrence’s duality in Paris, trying to uphold his own ideas of British interests in Arabia and, at the same time, honor his pledges to Feisal, was mirrored in his chosen wardrobe, a British officer’s uniform and an Arab headdress – authentic to neither one calling nor the other, and satisfying neither his generals nor Feisal. Feisal was more of a realist than Lawrence. He played both sides, courting the French while sharing the limelight of the great Lawrence performances – Lawrence sat for portraits by virtually anyone who asked, and the wives of diplomats were apt to swoon at his appearances.

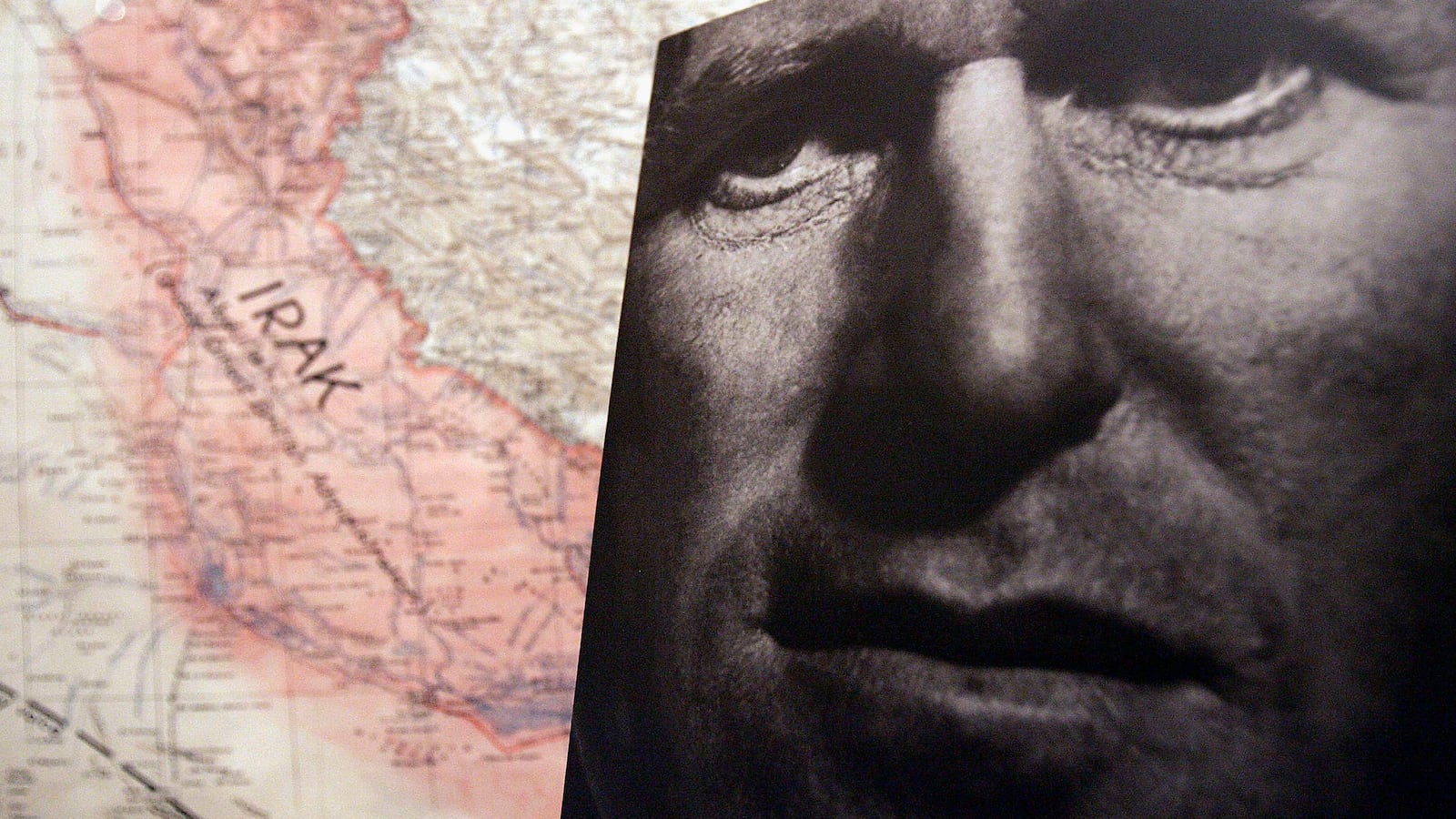

Feisal never got Syria. The royal Hashemite dynasty was given the newly-mapped state of Transjordan (now Jordan) with their capital in Amman. In fact, Lawrence had little influence on the grand carve-up that included a French-dominated Syria and an inherently unstable mash-up called Iraq – the latter largely the brainchild of a former mentor of Lawrence’s, Gertrude Bell, another lover of deserts but a far more politically astute “expert” on the region, who was also far more loyal than he to the imperial design.

It’s easy to blame the post-Ottoman land grab by European powers for today’s Middle East violence, but that is far too simplistic and self-serving. It was inevitable that the fall of the Ottomans would leave the disposition of western power in the region unresolved and that only the existing powers of the day would resolve it – there was no organized movement for Arab self-determination to make counter-claims in the court of world opinion. In Palestine the British were just as determined to block Zionist claims to a Jewish homeland as they were to block Arab aspirations for their own territory.

Rather than lament the cynical and arbitrary cartography of the time it would be better to listen again to those words of Lawrence’s: “…the old men came out again and took our victory to re-make in the likeness of the former world they knew.”

From the CIA coup in 1953 that kept the Shah of Iran in power to the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, western policy makers have also been pursuing “the likeness of the former world they knew” to preserve their own perceived national interests rather than acknowledge how fragile and combustible that world really was.

Like the British Intelligence Department in Cairo in 1915, they assumed the right to design states that conformed to their own cultural instincts, even if that meant sending in the military to achieve it. They never understood the odium felt by a people living under an alien occupying army and so they have repeated the many fiascoes of imperialism. And so it goes on, seemingly forever. Senator Lindsey Graham, for example, is the classic recidivist and strategy simpleton, calling now for U.S. boots on the ground to defeat ISIS in Syria.

The truth is that we’re not clearing up a mess left by Lawrence, Gertrude Bell and the old 20th century European realpolitik, we’re trapped in a repetitive cycle of foreign misadventures designed in the 21st century in Washington D.C. with far more lethal consequences to us than the old Great Game.

The Syrian cities that Lawrence fondly described in his Cairo memorandum, Homs, Hamah and Aleppo, are now gravestones marking the disintegration of Syria and the rise of a self-proclaimed Caliphate that he could never in its all its ghastliness have imagined.

Clive Irving wrote the story for A Dangerous Man, Lawrence After Arabia, an International Emmy-winning television drama starring Ralph Fiennes as Lawrence, available on Amazon instant video.