In the next few weeks, as the 2014 soccer World Cup is in full flow in Brazil, we should have proof of whether Qatar won its bid to host the 2022 soccer World Cup by means of good, old-fashioned bribery. If the answer is yes, there is every chance that the news will throw a malign shadow over the tournament in Brazil. Gaudy, dodgy FIFA, the governing body of world soccer whose operating methods are a permanent invitation to corruption, will have no dignified option but to strip host-nation status from Qatar and begin proceedings to confer it on another nation. This would be unprecedented, and enormously ugly, but the cup’s sponsors—Visa, Adidas, Sony, Coca-Cola, and others—are indicating that nothing else would satisfy them: A cup in Qatar would sully their brands.

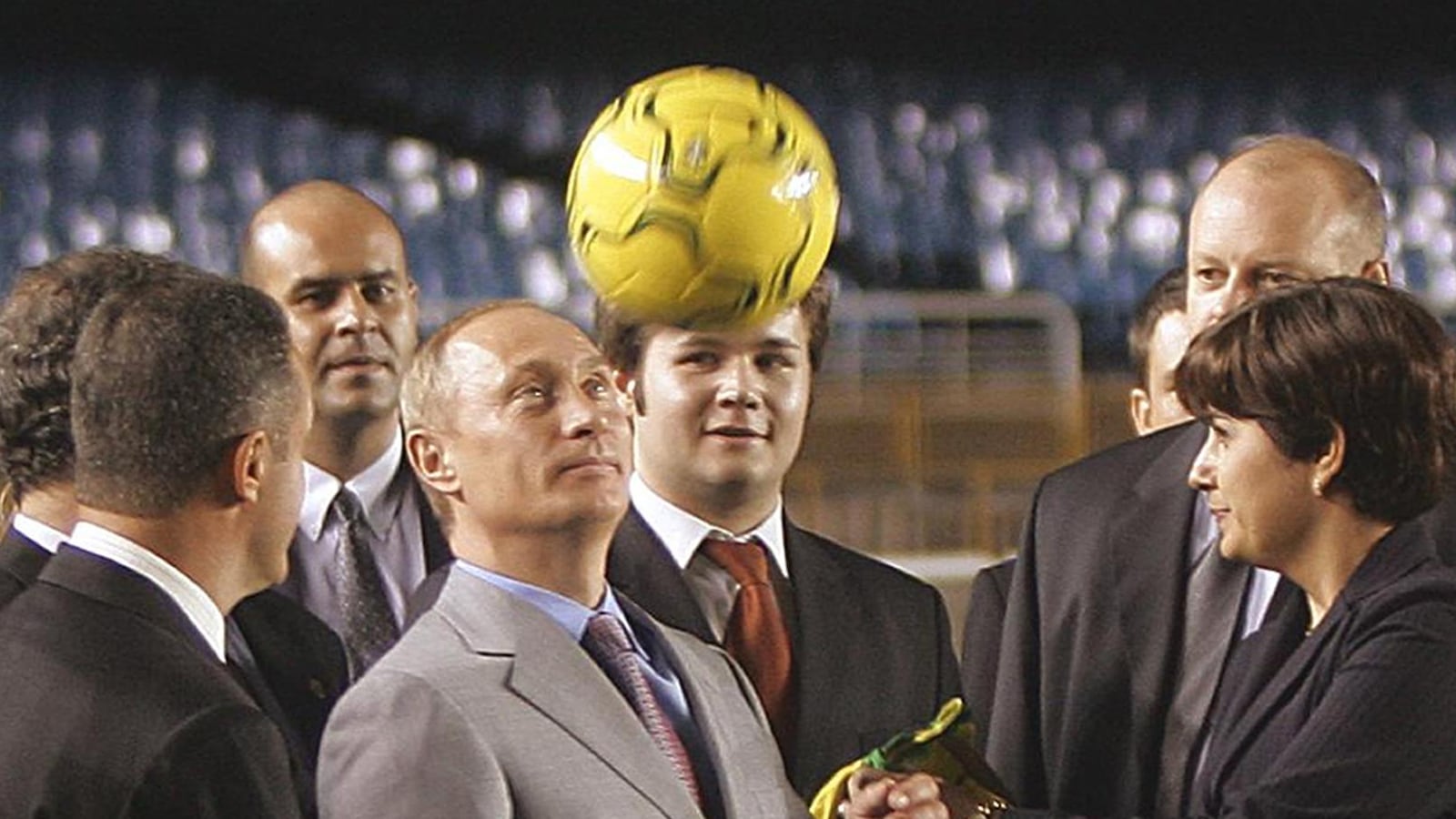

And yet, even as we grapple with the question of whether suitcases full of cash did the hosting trick for the Emirate, we ignore the equally pressing question of another controversial World Cup-in-waiting: that of 2018, in Russia. Compared with Qatar’s alleged transgressions—the grubby purchase of votes and favors—Russia is in full-scale breach of international law, having invaded and annexed the territory of a neighboring, sovereign state. If Russia is still in possession of Ukrainian territory in 2018, why should that country be entitled to host the World Cup? (With Vladimir Putin certain to be in power that year so long as he’s capable of drawing breath, it is almost certain that the expansionist nature of the Russian state will remain essentially unchanged.)

The larger goal, of course, is not to strip Russia of the cup as an end in itself, but to find ways to hurt Moscow so much that it will relinquish the territory it has annexed from Ukraine. As we have seen in the weeks that followed the gobbling up of Crimea, there is little will in the West to embark on the sort of economic sanctions that could hobble the Putin-state. In fact, the modern history of economic sanctions suggest that such measures can, in the case of a stubborn and resourceful renegade, lead to a hardening of national resolve, as was the case with South Africa in the Apartheid years.

The example of South Africa, however, also shows that sporting sanctions can bite—and bite painfully, especially in a state with sporting prowess and pedigree. So why not start—right now—to threaten to move the 2018 cup out of Russia, where memories of the 1980 Olympic boycott are still raw (especially in Putin’s neo-Soviet circles)?

That World Cup is far enough away to allow a pivotal question to be asked immediately, one that would apply to Qatar, too: In awarding the World Cup to a host nation, shouldn’t there always be a designated “fallback host,” a runner-up that has formal hosting rights in the event that the designated host finds itself unable—or is found unfit—to host the cup? If that had been the norm already, FIFA would not now find itself in uncharted waters, asking itself what to do in the event that Qatar capsizes. We would have had a ready-made alternative, as we would have had, too, for 2018.

Those who lost out to Russia had all the conventional qualities of a World Cup host, and were all entirely worthy: England; Portugal and Spain (bidding jointly); and Belgium and the Netherlands (also bidding jointly). They had transparent bids, credible histories as footballing nations, and had not annexed another country’s territory since the end of the Second World War. Had any of these countries received a formal “stand-by” designation from FIFA, a lobbying campaign could have been initiated challenging Russia’s moral and political fitness to host the World Cup without also opening up the question of who the alternate host would be.

Given international rankings and comparative abilities, there are usually around 10 European Union teams in every soccer World Cup. Add to that the U.S., Japan, and South Korea, and one has a dozen teams whose absence from the cup would be enough for sponsors to consider pulling out, too. In that event, Russia’s hosting of the 2018 World Cup would almost certainly unravel. FIFA, not an organization to walk away from money, would scarcely countenance a situation where the money walks away from it. It would have no choice but to revoke Russia’s hosting rights and award the cup to a country which other Western countries (and the Western companies that are sponsors) find acceptable.

With its vast distances, many ugly cities (beyond St. Petersburg and Yekaterinburg), and a xenophobic population, Russia isn’t a natural fit for a tournament that celebrates a joyous spontaneity of skill and diversity. Russia bid for the cup purely to bolster its international prestige, and, given its indefensible conduct on the international stage, it would only be fitting to find ways to deny Moscow the prestige it craves. No country has the unfettered right to host the World Cup—and certainly not one that seizes by force the territory of others. The aim of this exercise, one has to believe, is to maneuver Moscow into the circle of good global citizenship. And a serious debate on taking away the 2018 World Cup would help achieve that goal. So, let’s kick off…