The death of Levon Helm from throat cancer on April 19 has silenced one of the great voices in American music.

There was something oracular about that voice, something that sounded as old as time itself. Even when Levon Helm was young, he had a voice that spoke to you with the authority of something graven in stone. But it was a voice that could also tease, and cut up, and sound as full of mischief as a 10-year-old boy on the first day of summer vacation. It was, in other words, the perfect voice for a rock and roll singer, maybe even the voice of rock and roll itself.

Like real estate, rock and roll gets most of its mojo from location, location, location, and in that respect, Helm was one lucky boy. He was born Mark Lavon Helm in 1940, in Elaine, Ark., the son of Nell and Diamond Helm, a cotton farmer. The parents loved music, and they encouraged their children to love it too. In Levon’s case, it didn’t take much persuading. He remembered seeing Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys when he was 6, and vowing then and there to be a musician. “This really tattooed my brain,” he said. “I’ve never forgotten it.”

Medicine shows—those weird amalgams of patent medicine hucksterism, string band music and minstrelsy, in which both black and white performers “corked up,” i.e., appeared in blackface—were in their last days when Levon was a boy, but they were favorites of the music-loving Helms. Decades later, memories of those shows would resurface in The Band’s song “W. S. Walcott’s Medicine Show,” which took a scrap of it’s title from the famous F.S. Walcott’s Original Rabbit’s Foot Minstrels, which toured the South for almost half a century and featured such performers as Ma Rainey, Big Joe Williams, and Rufus Thomas.

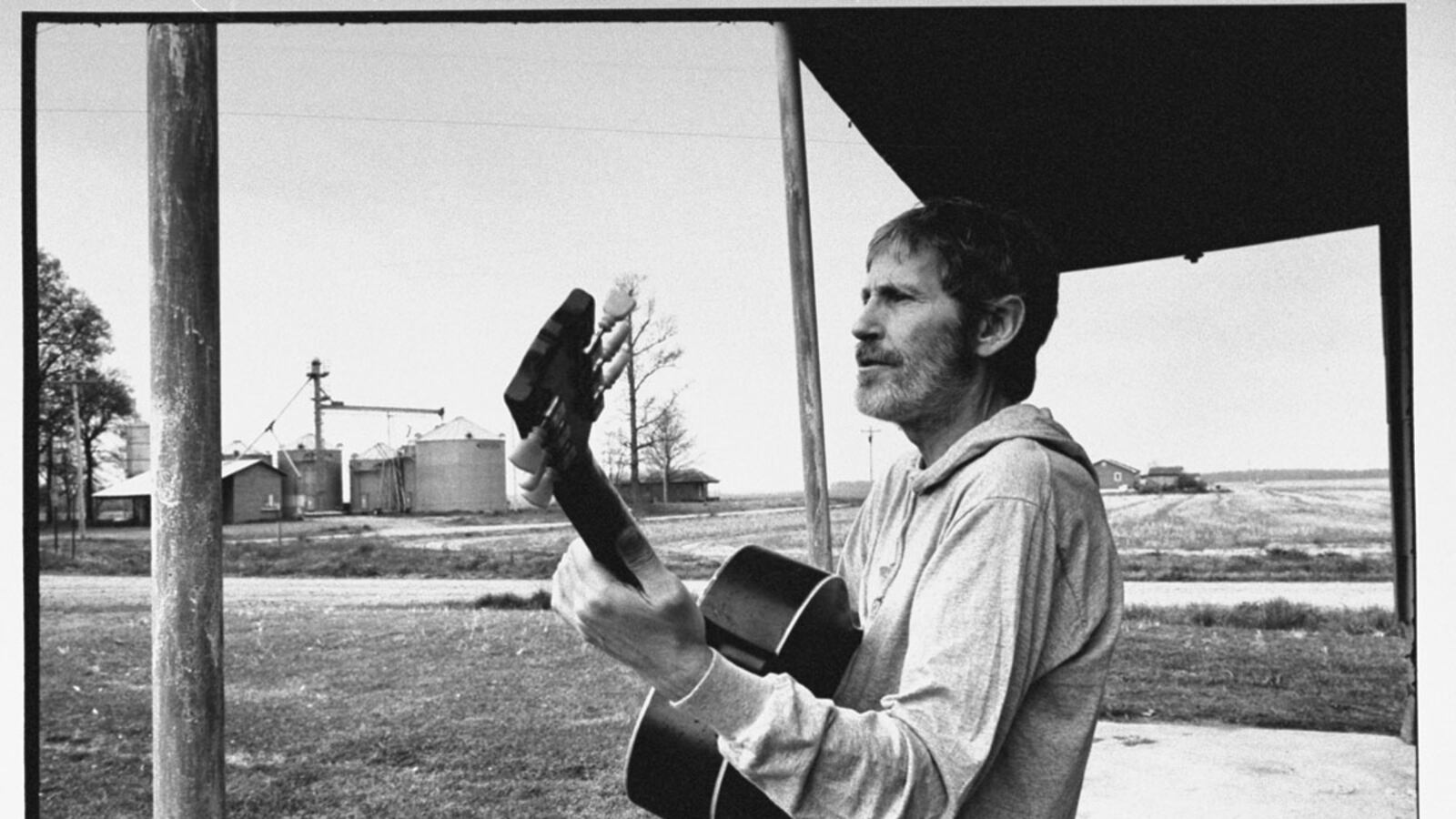

Levon’s father gave his son a guitar when he was nine, and Levon built his sister a washtub bass. Together they killed on the 4-H circuit. When he wasn’t playing, he was listening, and he was in the perfect spot to get one of the greatest educations in American music that anyone has ever received. Blues, jazz, country, rhythm and blues and a baby called rock and roll were all right there, intermingling like crazy in the Mississippi Delta, the Arkansas cotton fields, the dives of Beale Street in Memphis, and Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium, from whose stage the Grand Ole Opry broadcast its Saturday night show every Saturday night. When he was 14, Helm attended a show headlined by Johnny Cash and Carl Perkins, with a very young Elvis Presley further down on the bill. Most days, when he wasn’t in school, he could be found at KFFA in Helena, Ark., where he watched bluesman Sonny Boy Williamson do his King Biscuit Time radio show.

In high school, Helm had started his own rock and roll band, the Jungle Bush Beaters. If that name sounds suggestively racist to our ears, bear in mind that these were white boys in Arkansas in the mid-’50s. For them to take a name like that suggests not racism but approbation. Musicians were colorblind in this country long before anyone else, and no one was ever more colorblind than Helm.

By the time he was 17, Helm was sitting in occasionally with Conway Twitty’s band, and as soon as he got out of high school, he went pro, drumming for the rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins. Flush with a couple of hits (“Forty Days” and “Mary Lou” sold 750,000 copies and won them a spot on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand), Hawkins expanded his band from the trio Helm had joined to a quintet that besides Helm featured four Canadian musicians—Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, Robbie Robertson, and Garth Hudson. Ronnie Hawkins and the Hawks toured the juke-joint circuit for several years, soaking up influences, honing their sound, but mostly just weathering every imaginable club and dive. There was the night they played a Texas joint called the Starlight Lounge, which they discovered was called the Starlight Lounge when they got inside and found that it had no roof. There was the night they played for an audience of two, and a fight broke out. There was more than one night when they played in dives so rough the band had to stand behind a chicken-wire screen to be protected from flying beer bottles.

Can you hear all that in the songs those musicians made once they left Hawkins and—minus Helm, who took a couple of years off and went back South to work on the oil rigs in the Gulf—started backing up Bob Dylan in 1965 before going out on their own as The Band? You can certainly hear some of it, because none of their rock contemporaries, with the possible exception of Jimi Hendrix, had their experience as seasoned professionals by the time they made it big. They were like the grown-ups in the room wherever they went.

In his marvelous autobiography, This Wheel’s on Fire, Helm talks about what he heard on The Basement Tapes when he rejoined The Band in Woodstock, N.Y., where the group had been woodshedding with Dylan, writing and recording songs in a homemade studio. Listening to the tapes, Helm “could tell that hanging out with the boys had helped Bob to find a connection with things we were interested in: blues, rockabilly, R&B. They had rubbed off on him a little.” Dylan’s immersion in the folk tradition, with its emphasis on ancient melodies and lyricism, rubbed off on his running mates as well.

You can most definitely hear all that in The Band’s first two or three albums, which are as timeless as anything in American pop, and nowhere is it more obvious than the songs where Helm sings lead—“Rag Mama Rag,” “The Night they Drove Old Dixie Down” or covers (which they made completely their own) such as “Don’t Do It” or “Rock and Roll Shoes.” When that cracked, weathered but limber voice opens up with “Virgil Caine is my name, and I served on the Danville train,” you could swear that you’re listening to a Civil War vet singing you his beautiful, tragic history. Helm’s vocal chords, a crucial marriage of genetics and place and time, channeled the past and put it in the present tense.

He would go on to a solo career full of Grammys and other accolades. He would weather a bout with throat cancer and bounce back for one last round of great music making in the first decade of this century, before cancer claimed him at last. But the through-line to it all is that marvelous voice, an utterly American sound that somehow for five decades embodied the field hollers, Delta blues, minstrel shows, rockabilly, mountain ballads, and country crooners all in one exhilarating package. If you want to hear what American music sounds like at its best, listen to what Levon Helm left behind.