In a small classroom at Monrovia’s prestigious College of West Africa, Victor W. Birch, a young history teacher, stands in front of a class of students in blue-and-white uniforms. Behind him, the theme for the day’s lesson is written in neat cursive: “The territorial expansion and encroachment of Liberia.”

With sweeping hand gestures, Birch speaks of the creation of Liberia, that small West African nation founded by freed American slaves who subjugated the land’s original inhabitants in the style of their former masters while enriching their own political and economic fortunes.

Ever since Liberia declared independence in 1847, it has faced a heated internal battle over its national identity, which culminated in a 14-year civil war from 1989 to 2003 that left more than 250,000 dead and the nation's infrastructure in tatters.

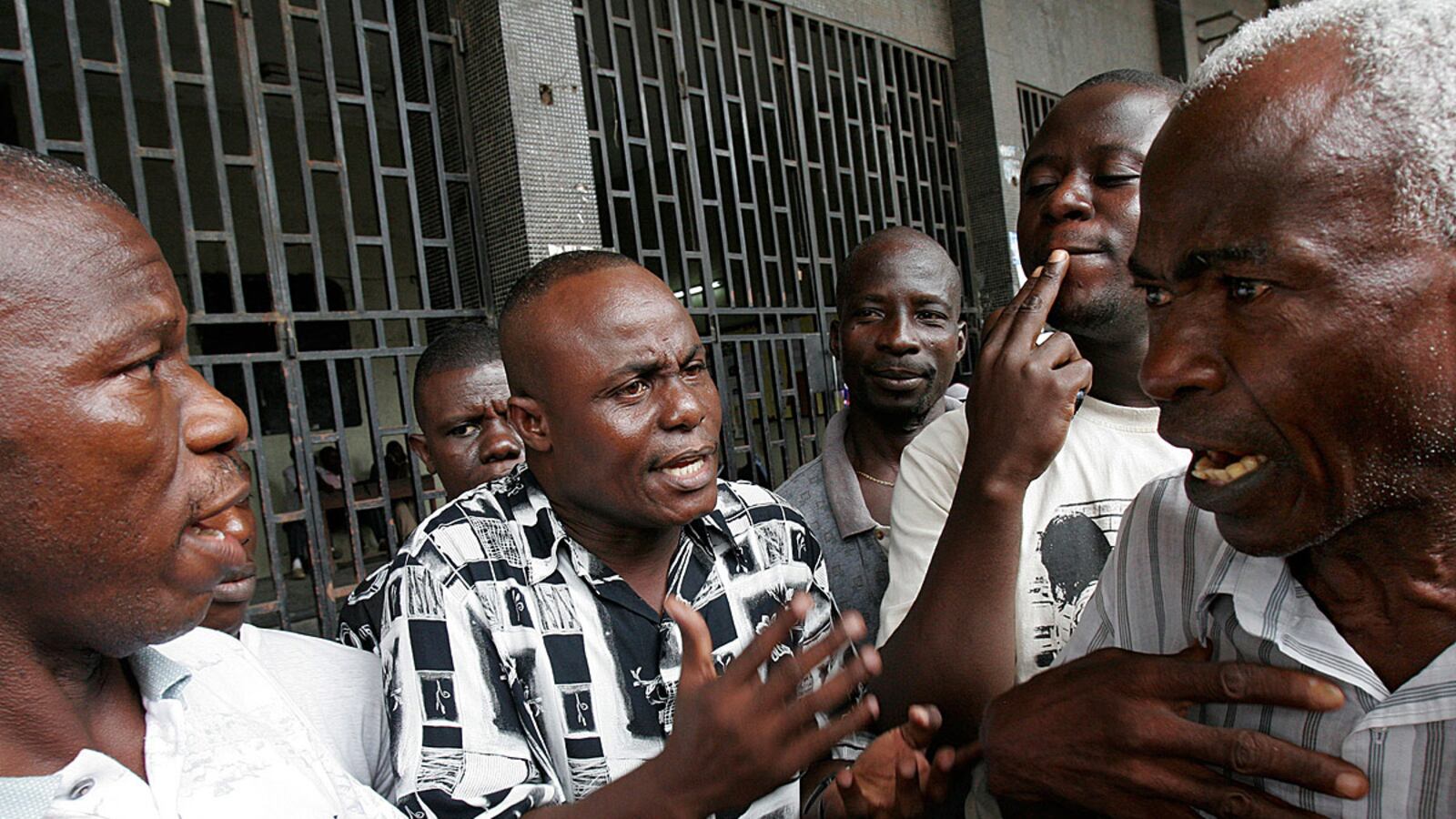

Liberia’s fractured history was again in view last week when The Hague announced a guilty verdict in the trial of Charles Taylor, the warlord turned elected president. Taylor was convicted of aiding and abetting war crimes and crimes against humanity in neighboring Sierra Leone during that country’s brutal civil conflict. In Monrovia, the verdict was welcomed by some Liberians and condemned by others, particularly former child soldiers for whom Taylor is a father figure—a sign that the verdict marks only the beginning of soul-searching for the country.

For most of its history, Liberian society and political life were dominated by the Americo-Liberians, descendants of the freed slaves, who mimicked the lives and culture of their onetime owners in the U.S. Citizenship was denied to natives until 1946, when then-president William V.S. Tubman granted them the right to vote, and it wasn’t until the 1960s that tribesmen won legislative representation. For 102 years, Liberia was a one-party state, with the True Whig Party enjoying a monopoly.

It was a state of affairs that many before the war described as “apartheid,” says Togba-Nah Tipoteh, a native Liberian and founder of the Liberian branch of the Movement for Justice in Africa.

That history was abruptly shattered in April 1980, when a 28-year-old noncommissioned officer, Samuel K. Doe, led a coup, slaughtering President William Tolbert in his mansion and executing most of Tolbert’s cabinet on a beach behind the Army barracks. Doe’s bloody reign precipitated two decades of violence.

But Liberia’s notorious modern history—from Doe’s coup and his own torture and death at the hands of rebels; through Taylor's presidency, his exile to Nigeria, and his war-crimes trial; and up to President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf’s reelection late last year—is conspicuously absent from the textbooks that circulate in Liberian schools. When the prewar generation, including Johnson Sirleaf, was growing up, young Liberians read the civics books of A. Doris Banks Henries, a Yale-educated Methodist missionary whose The Liberian Nation: A Short History starts in 1839, when freed American slaves sailed to Africa to bring “civilization” and Christian values to a “savage, primitive, belligerent people.”

Henries’s books effectively erased the oral history of the migrants from Sudan and North Africa who traveled to Ghana in pursuit of gold and settled in Liberia, and of the descendants of great sub-Saharan empires. The books also ignored the multiethnic, multilingual, multifaith complexity of the societies that existed when the settlers arrived.

Little has changed in Liberian education since then, as seventh grader Israel Lewis can attest. Lewis, a student at the J.J. Roberts School—named for Liberia’s first president—was taking a break from an afternoon game of football on the same pitch where, in 1980, 13 of Tolbert’s cabinet members were stripped, tied to wooden stakes, and shot one by one.

“I learned about how the Europeans came to Africa. The Normans from France came. Then the Portuguese ... The English and France began with the trade of gold for salt. Our own people started to give our brothers away to work on cocoa plantations,” Lewis says, keeping the ball moving between his feet.

Of the war years, which ended with the signing of the Accra peace accord in 2003, Lewis only says, “We were fighting among ourselves, and it shouldn’t be like that.”

Across the unpaved road from J.J. Roberts, young men with photocopiers—the country’s makeshift office suppliers—hawk prints of history books by Prof. Joseph Saye Guannu, one of the country’s most respected political historians. The tomes—bound with staples and partially paid for by UNICEF—begin by recounting the formation of a migrant tribal system before the Americans’ arrival in the 19th century and end with the coup of 1980. Now many Liberians say that coming to terms with the more recent past will be an essential project—and part of a larger movement to understand the historical conditions that created the civil war.

“Many do not identify with our national motto, ‘The love of liberty brought us here.’ It's a historical fallacy,” says Guannu.

“Before the coup, there were people around challenging this one-dimensional view,” says Elwood Dunn, a professor at Sewanee, the University of the South, in Tennessee and a former minister—one of the few, along with Johnson Sirleaf, to escape execution following Doe’s coup. “But the movement was hijacked by revolutionaries of entitlement. We never got a chance to digest what we were talking about in the 1970s, and so we are still trying to figure out who we are.” This is no small task, says Michael Keating, a Liberia expert at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. “In a place like Liberia, where you never really had an honest history, it’s going to be a long journey to construct one.” Complicating matters are the fact that 65 percent of the country is illiterate and tens of thousands grew up during the war years, when schools were closed, making them a “lost generation.”

Still, the project is essential for the nation’s survival, says Nobel laureate Leymah Gbowee, now the head of the Liberian Reconciliation Initiative, which will be working in conjunction with a range of government bodies on unity.

“Liberia has a serious identity crisis,” says Gbowee. “Every war has an agreed-upon narrative, and what is the narrative of the war that we fought? Every ethnic group will explain the war to their children from their perspective. Then those children internalize it, depending on who was the victim or victor, which is cause for future conflict.”

Johnson Sirleaf also addressed the need to rehabilitate Liberia’s “national spirit” in her January inaugural address, after a tense election that followed the boycott of the main opposition party and a deadly face-off between security forces and protesters.

Johnson Sirleaf wore a traditional lapa suit and headdress and stood on a stage draped in red, white, and blue outside Capitol Hill in Monrovia. Cannons were fired, brass bands played, and American-inspired pomp and pageantry abounded.

“Healing with the past is a means to an end, and that end is to be able to move forward as one people, united,” she said. “To be able to look forward and steer a clear path, we must renew our sense of self and nationhood, of what it means to be Liberian, of our common destiny. This is the spirit of patriotism.” The Liberian government is attempting to create new patriots and a new Liberia through a national “visioning” exercise, Vision 2030, that will consult with people at the national and district levels.

The national steering committee for Vision 2030 is chaired by Tipoteh, the founder of the Movement for Justice in Africa. He also chaired Vision 2024, initiated by Taylor and held in Monrovia in 2001. That was shut down personally by Taylor after four days when its resolutions—including doing away with the national motto—were deemed too controversial.

But with the collapse of Taylor’s regime and the second democratic election since the end of the civil war, Tipoteh thinks Vision 2030 will be different. Tipoteh grasps for a phrase and ends up with something more sober than optimistic.

“The essence of it for Liberians is to come out to say what kind of Liberia they want to see tomorrow and in the future ... Having only a few people run the show has led to war and violence.”

Back in the classroom at the College of West Africa, Birch launches into a discussion on the fairness of Liberia’s Constitution, which decrees that only those of “Negro descent” can be citizens. “Liberia has the most racist constitution in the world,” Birch says. “I hope that it will change.” Some agree, and others object. But inside and outside the classroom, the question of who is a Liberian continues.

Clair MacDougall is a journalist based in Monrovia. Emily Schmall is a journalist based in Buenos Aires and formerly the Liberia country director of New Narratives.