“This can’t be good for anyone.”It was May of 2012. The manager of my congressional campaign, a Jewish lawyer from Washington, D.C., had found his daily dose of angst dangling from the mirror of my solid, union-label Ford Flex: an air freshener brandishing red, white, green and black in the form of the Palestinian flag. My husband Marty had picked it up at the Middle East food market, less as a sign of solidarity, more as a sign of irony—he liked to ask people riding with us in the car if they knew to which country this flag belonged.

This can’t be good for anyone, our campaign manager said again, even after listening to Marty’s protests. The air freshener went into the glove compartment. It’s probably still there. My husband, the activist, a repeat visitor to Israel/Palestine, was a nuanced thinker frustrated by the sound-bite reality of a national congressional campaign. We both assumed I was pro-Israel: we supported peace, and we were shoestring relatives of prominent Jewish Senator Carl Levin and his brother Congressman Sander Levin.

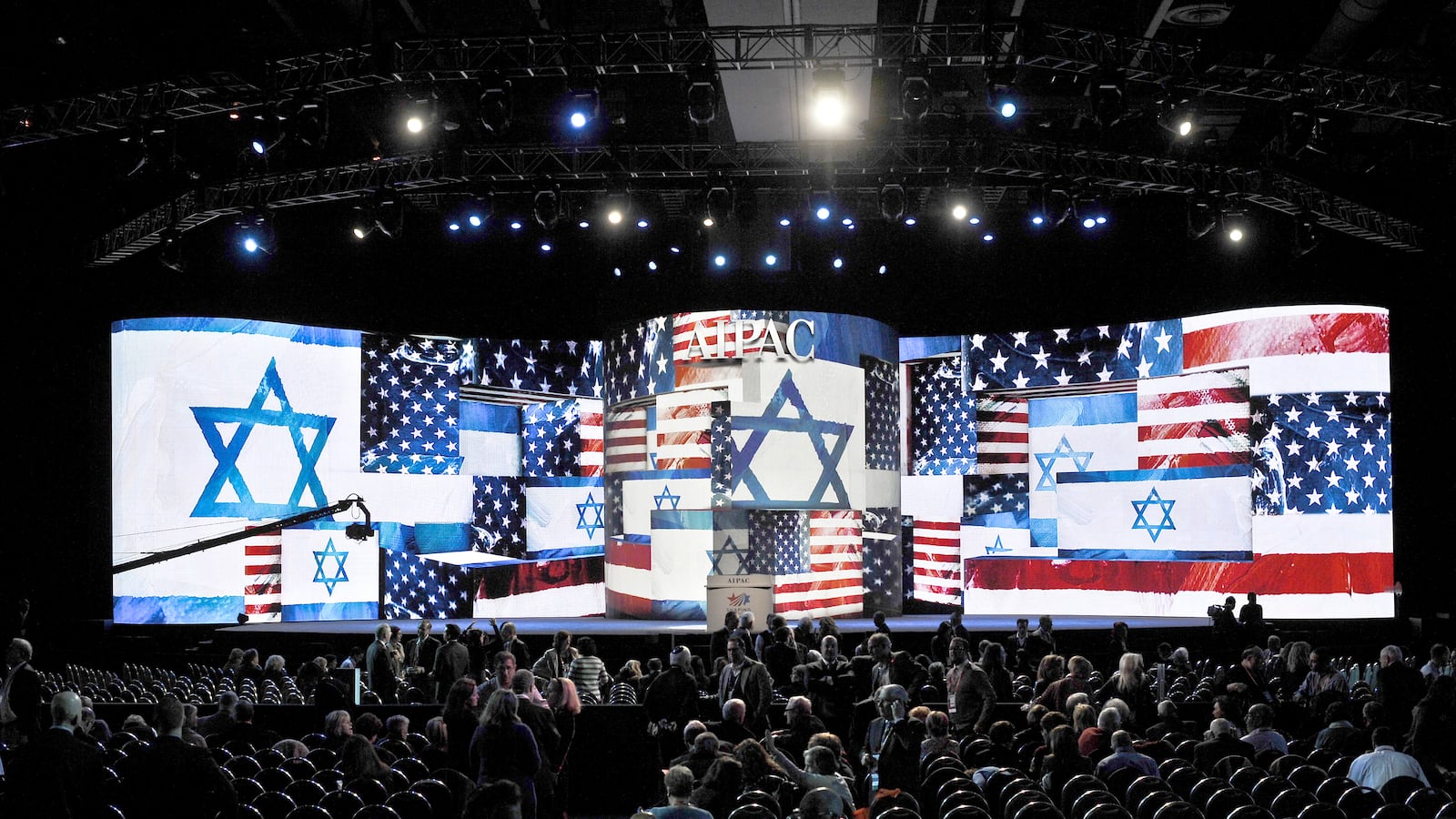

The idea that an air freshener could dampen my bid for U.S. Congress in mostly rural, conservative Northwest Ohio seemed ludicrous at best. There were few Jews and fewer Palestinians—it remains a district of stalwart Christians, most of whom are unengaged with the Middle East. And of course I was pro-Israel insofar as I was pro-peace; I was a Christian. I was about to learn that I wasn’t pro-Israel enough; at least, not enough to garner an endorsement or any cash support from the political action committee that spreads the wealth to Democrats and Republicans who promise unequivocal support for Israel. Our naivete would soon force me to make a decision that would tip the balance of the campaign.Late in July, we traveled to Washington, where my campaign manager had scheduled a meeting with AIPAC in a spotless office on H Street. During the interview, I was presented with false dichotomies of the “you’re either with us—or you’re not” variety. I was asked to write a white paper showing my unflagging come-what-may support of Israel, her politics, and her military strategies. I found this deeply unsettling—how could I give a blanket endorsement for Israel when I was far from being able to do so regarding the policies and practices of my own government?

Back in the cornfields of Ohio, I was left to wrestle, and to wonder, and to finally accept—I would not be an AIPAC-endorsed candidate. I could make the fundraising calls to New York and Chicago, but I didn’t have the “juice.” The dollars trickled. I wrestled. Should I have capitulated?

On November 6, I lost that election to incumbent Bob Latta, garnering just under 40 percent of the vote. I raised nearly half a million dollars, mostly in small increments from 2000 individuals representing every state in the country. Bob picked up the phone, made a few calls, and gathered $1.2 million in his war chest. He had signed off with AIPAC years ago.

AIPAC may have been done with me, but little did I know that I was far from done with the Middle East and the troubling, complicated bricolage of its politics.

In the quiet after the campaign, I spent time recuperating, baking cookies with my daughter whom I hadn’t seen for more than 20 consecutive minutes in a year, waiting for the new semester to start at the university where I taught.

After a week or so, the phone, which had been resting in quiet post-campaign bliss, began to ring. Marty and I, both Lutheran pastors, were asked by a bishop’s assistant in Detroit to interview for global mission work with the Palestinian Lutherans in East Jerusalem, Jordan, and the West Bank. We didn’t even have passports.

The conversations lasted deep into the night. We had to think about our children, my aging father, our “domestic tranquility,” and the far-reaching implications of what life in the Middle East might mean for our lives, my political career, and our family. We were tempted to say, This can’t be good for anyone. But deep down, we knew that saying no to this opportunity would leave us always cursed with the dangling banner of what if.

We interviewed on November 28. On December 6, we were offered and accepted the position—a split call to serve the ex-pat congregation in Jerusalem and assist the Palestinian Lutheran Bishop whose platform is peace based on justice with reconciliation and forgiveness. We rented the house, put our belongings in mothballs, and left on February 20. Our kids go to the Anglican school on Ha Nevi’im Street. We live on the Augusta Victoria campus on the Mount of Olives. We work at the Redeemer Church in the Old City, a short walk away from the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

Every day we witness signs of the conflict—the tension at checkpoints, work permits denied or granted, elderly voices telling stories of dispossession from their homes (both Israeli and Palestinian), socio-economic disparities, and so on. Our Arabic tutor lives in Beit Hanina, less than a block from the concrete wall that, for good or ill, splits the neighborhood in half in the name of security. Every time there is something on the news back home within four hundred miles of us, we get messages of concern from our friends, some of them sounding the refrain: This can’t be good for anyone. It has become a cliché in our family. When my ten-year-old spills her milk, it can’t be good for anyone.

As for life here, we’re building this boat as we sail it. We are not Middle East policy experts. In our naivete, we sometimes go rushing in where angels fear to tread. We are learning to laugh at ourselves, to eat our pizza with corn on it, and to slowly and painstakingly listen and learn. We are struggling to make miniscule contributions to a just peace and a two-state solution. This can be good for everyone.