Last year, during another flare-up of the euro-zone crisis, a friend from Singapore called me up in the middle of the night with an urgent question: “Kevin! The world economy is on the brink of collapse! I’m worried for you—how much cash do you keep at your place? My banker says you should keep at least $500,000 in cash at home at all times, just in case something happens.”

This was not a joke—my friend truly was concerned for my well-being. (For the record, there isn’t a spare half-million stuffed under my mattress—more like $8 in old pennies rusting away in a tin somewhere underneath my kitchen sink.) But this anecdote perfectly illustrates what life is like whenever I come into contact with a certain crowd.

F. Scott Fitzgerald famously said that “the rich are different from you and me.” But I wonder what else he might have said if he could eat lunch at one of Hong Kong’s private clubs and watch ladies draped in haute couture and millions of dollars’ worth of “daytime jewelry” pick at their dim sum while speed dialing their stockbrokers. Or if he could witness the long lines of mainland Chinese shoppers camped outside the Hong Kong branches of Gucci, Chanel, or Louis Vuitton every single day—as if it were some sort of bread line in Siberia—desperately awaiting their turn to rush in and buy up everything in sight.

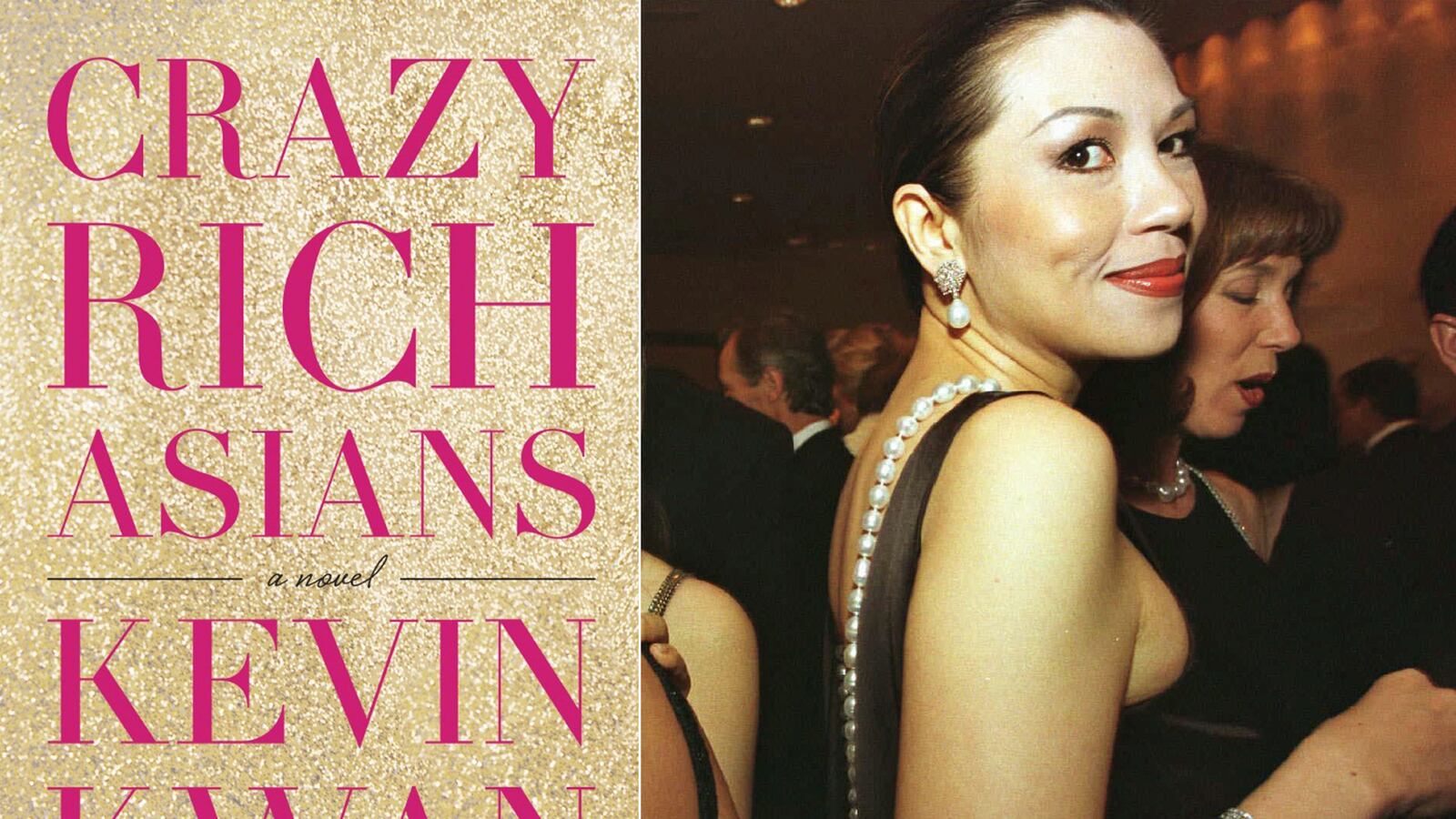

Over the past few years, as Asia’s new gilded age has been breathlessly chronicled on the front pages of newspapers, it occurred to me that while plenty of articles were being written about the ever-rising number of billionaires in China (122 at last count, according to Forbes) or the Asian luxury consumer (which now accounts for more than 50 percent of global luxury sales), few journalists have reported on the fact that outside of mainland China, there has long existed a class of fabulously wealthy Asians—scattered throughout Southeast Asia and beyond—who have very quietly been going about their lives for centuries. My novel, Crazy Rich Asians, was inspired by this world.

It is a world I have, for better or for worse, been exposed to since birth. I spent the first 12 years of my life growing up in Singapore. Back then, in the early 80s, it was still a tropical island at the tip of the Malay Peninsula striving to shine on the world stage. As a child, I could bike down the hill from my house and grab an ice-cold bottle of soda from the neighborhood grocer, which was nothing more than a corrugated metal shack run by two Indian men clad in sarongs. Today, that shack has been replaced by a $20 million bungalow, and Singapore is better known as the country with the highest percentage of millionaires in the world (17 percent of its resident households).

But numbers don’t really do much justice to the jaw-dropping displays of wealth one encounters—it simply that has to be seen to be believed. No matter where I land in Asia these days, I feel as if I’m on some surreal Jackie Collins-meets-Amy Tan acid trip:

I arrive in Hong Kong and am met by an entourage of four maids at the airport. (Still not sure why my host thought it would take four women to help me with one suitcase.)

I visit the Philippines and discover my friend—who leads a seemingly normal life in the States—surrounded by bodyguards in her hometown of Manila. At night, we go club hopping and find that everywhere we go, her 60-something-year-old father has already beaten us there and has put our names on the VIP list.

I go to Shenzhen, China, and am taken to a vast luxury spa with a hundred leather recliners and a hundred accompanying plasma screen televisions bolted to the ceiling. It’s past midnight, and the spa is packed with fashionably-clad fu er dai—“second-generation rich”—all blissfully reclining in leather chairs with their feet soaking in wooden tubs of warm water, staring at their televisions on the ceiling or texting on their mobile phones while two attendants administer simultaneous foot and neck massages.

But there’s always the flip side to all this decadence—the rich who can’t bear to spend a cent. I know an elderly society matron in Singapore who would rather walk in the scorching sun for blocks on end rather than have her chauffeur drive into the Central Business District at peak hour and pay the $1.50 surcharge. An heir to one of Asia’s most famous fortunes commutes to Manhattan from his tiny studio apartment in Queens and tells me he eats value meals at McDonald’s every day “to economize.” And then there’s the eccentric family friend who lived in a dilapidated garden shack until he passed away and left his astonished children a portfolio of blue-chip stocks worth hundreds of millions.

Over the years, returning from my trips to Asia full of stories like these, many of my friends have said, “This is insane—you’ve got to write this down!” But a few friends have listened to my stories with a little skepticism. Even in a city as affluent as New York, the lifestyles I described seemed simply unbelievable to them. One of these skeptics called me up recently with a story of his own. He had just returned from Seattle, and while on a tour of Boeing headquarters he was told that Boeing was receiving orders for 747s from Chinese billionaires, and one had even been built with a bowling alley onboard. It seems that for the wealthiest Chinese clients, your run-of-the-mill G-650 just will not do. When I called Boeing to confirm the story, their spokesperson said they haven’t built any 747s for Chinese billionaires and denied knowledge of any bowling alleys. How about 787s? No comment. 737s? Yes. And what custom features were their clients requesting? Putting greens, pizza ovens, and mah-jongg tables, she offered. Welcome to the world of Crazy Rich Asians.