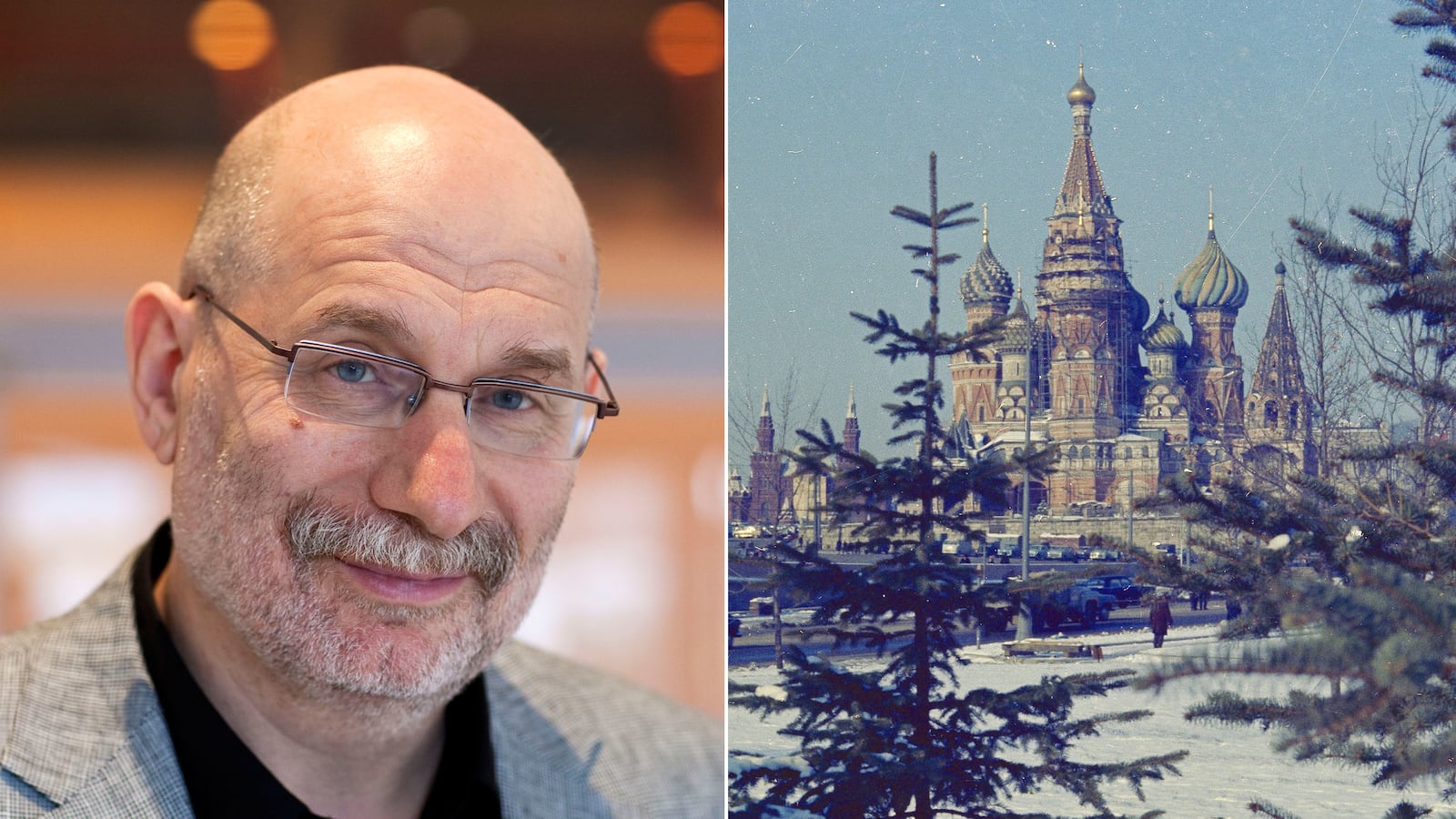

Boris Akunin, the popular Russian detective novelist—and one of the pen names of Grigory Chkhartishvili—announced last month that he was abandoning fiction and focusing on writing a political history of Russia. Akunin frequently shares his opinions on his influential blog, a platform from which he has organized talks and even mass demonstrations. Ever since Vladimir Putin laid claim to a third term as president in 2011, Akunin has emerged as one of the leaders of the opposition, organizing protests over evident fraud in the parliamentary elections that year. In a country where the president has demanded new history books that he must approve, Akunin is attempting to fight ideological whitewashing, one reader at a time.

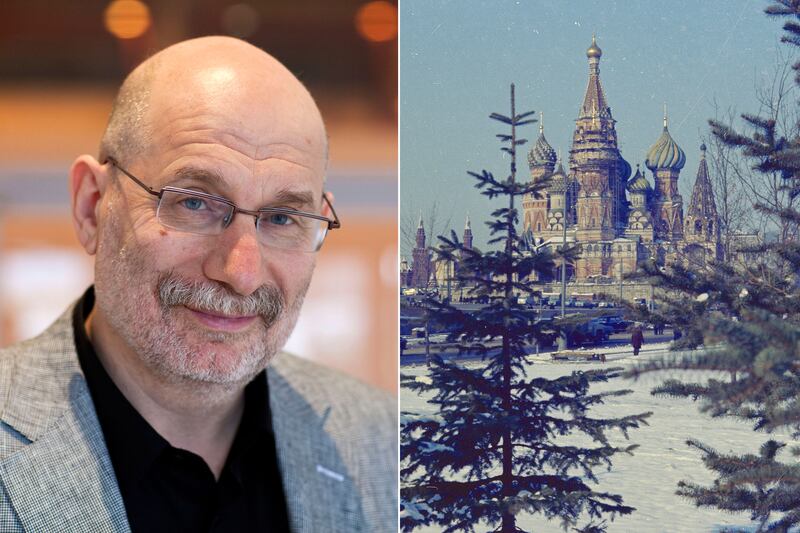

Can you describe the area of Moscow that your house is in?

The old center. Shabby, beautiful little churches. History all around—even underground—there are lots of secret tunnels from turbulent times hidden down there. Muscovites were always under oppression, or invasion, or siege: Tartars, Ivan the Terrible, Poles, Peter the Great, Napoleon, NKVD. People dug underground hideouts to conceal their goods, their treasures. Secret services, conspirators, bandits—especially in the district where I live—also contributed. Of course, I have many gruesome tunnels in my novels, with skulls, treasures, and sometimes even ghosts.

Do you think Moscow has greatly affected your work in that sense?

I am a Muscovite. Everything I know about life was taught to me by Moscow.

Where do you get the books you read, and where do you usually read them?

Nowadays, mostly, I read e-books. I also spend a lot of time in used-books shops. It’s a special treat that I reserve for myself when I feel that I deserve an award. I love very old books with marginalia. A couple of times I found 200-years dried flowers between pages. My biggest pleasure is leafing through albums of family photographs. The mystery of those faces and of gone lives intrigues me. Sometimes I find protagonists for my novels on those sepia cards.

Are there any places, outside of your house, that you can go to write?

Oh, yes. Over the years, I’ve developed a complicated system of writing-related movement from place to place. When I work on a novel, there are stages: idea, script, text. I live in four homes, depending on the stage. Moscow is perfect for having ideas, it’s so vital and unpredictable. Scripts I write in my country house, where it is quiet, but friends come and bring in a touch of chaos. Texts are better written in my French rural hideout, where nobody and nothing disturbs me. I also have a place in Paris, but Paris is useless for work. There I relax and recharge my batteries.

Was the move outside of Russia politically motivated on your part?

No. My stays in France are motivated only by stages of my writing. In fact, my whole modus vivendi is dictated by the needs of writing. But I rush back to Russia wenever something politically interesting or dangerous (usually it comes together) begins to happen here, even if it is harmful for my book. I wouldn’t be able to work normally anyway when my friends in Moscow risk getting arrested.

Is it difficult to be part of the Russian intelligentsia? Is there a pressure that comes with that?

No—if you can build within yourself a block against political issues. An average member of Russian intelligentsia usually can’t. Neither can I. But it’s a matter of inner choice.

Have you ever written things that, later, you’ve decided to edit out for political reasons?

Never. Fiction is not censored in Russia. The authorities do not think that literature is of any importance. God bless them for their sweet ignorance.

You write mostly about Soviet Russia, but do you try to pursue a politically motivated message?

I do it directly in plain Russian via my blog, which is quite widely read; through press interviews; and so on. I do not use fiction for imposing my political views on readers. It wouldn’t be fair. I write to entertain.

So then, I wonder how much of your descriptions, your narratives, your characters come from history books?

I place my characters (some of them are historical figures, though I always change a letter or two in a name, which still makes it recognizable) in situations that are essentially modern and where my readers can easily imagine themselves. All the principal moral dilemmas are more or less eternal, aren’t they? If not, then I am not interested.

Do you think your interest in Russia’s history came before your interest in literature?

History came first. When I was a kid, I pestered old people with questions about what life had been like in old times. I remember embarrassing some old ladies by demanding the year of their birth. As it was in the ’60s, many were born in 1880s. That sounded like music to my ears.

What are some of your favourite works of literature set in Moscow?

Anna Karenina. Master and Margarita.

And what about contemporary Russian writers?

I do not read contemporary fiction. It’s not healthy for someone who tries to write something of his own.