In 1957 my first child with Hazel was born, Valerie. Hazel, I, and the baby moved from my brother Alvin’s home to the 1100 block of Troy Street on Chicago’s West Side. Little did I know, on the next block over, on Albany Avenue, lived Little Walter. Our back doors were catty-corner to each other.

I learned harp from Daddy and then from listening to Sonny Boy Williamson. But that learnin’ was elementary school and high school. Hangin’ with Little Walter was college. When Walter had his first hit with “Juke” in 1952, everything changed for the blues harp players. The song was like a breath of fresh air for the blues. In terms of the harp, that record “Juke” was like before Jesus and after Jesus in the Bible. Because after it, everything changed for the blues. One of the old repeated stories is that before “Juke,” you could buy a harmonica for 50 cents. After “Juke” they were three dollars ’cause everybody wanted to play one.

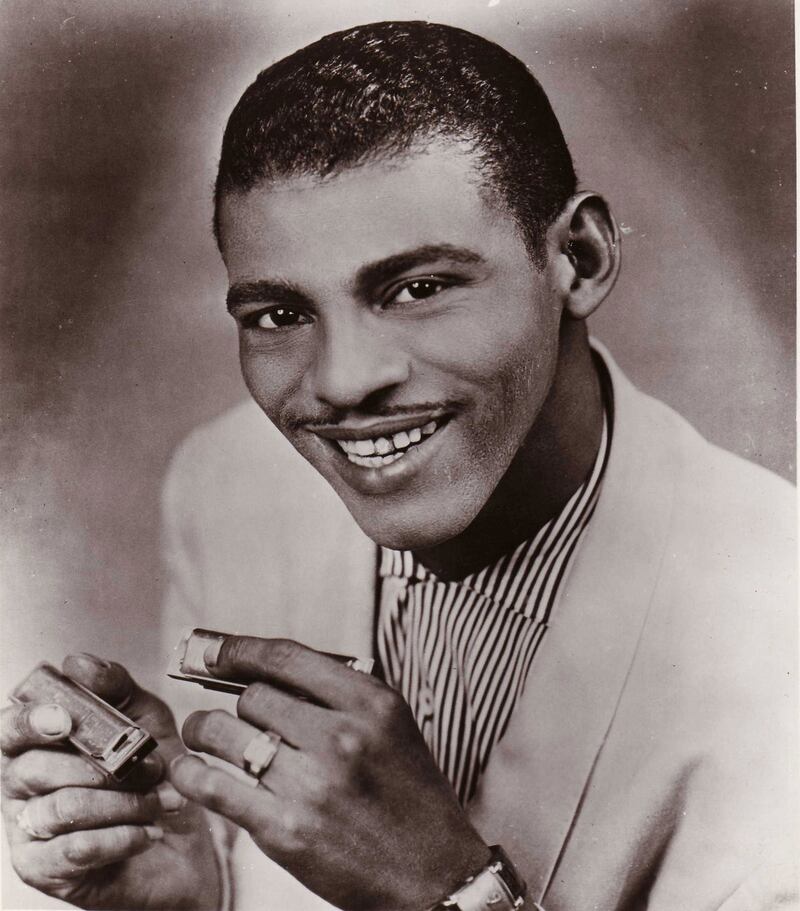

Blues musician Little Walter poses for a portrait playing his harmonica circa 1955.

Michael Ochs Archives/GettyIt pushed the harp out front in a fresh way. “Juke” was just a regular old boogie-woogie, but it began with a harp lick that would become famous. When you’re a young musician, if a lick on your axe becomes something that every ear has heard, you better learn that lick and learn it good. So every harp player including me had to know how to play “Juke” from top to bottom.

Everybody wanted to take the credit for the song’s opening riff, and pieces of it may have been ripped from other songs. But despite what Junior Wells and a bunch of other harp players said, that shit belongs to Little Walter. And even if the opening lick was ripped from someone else, all his playing through the song made it a hit.

I knew a pretty good amount about playing harp, but Walter talked to me about gettin’ a sound, a certain tone. Taught me more about the basics of tongue-blocking. He said, “That’s how you git it dirty—make them notes bend. If your tongue ain’t hurtin’ after you’ve played for half an hour—you ain’t shutting the door hard enough with your tongue.” That technique, along with a few others, gave Walter his one-of-a-kind sound. Walter could make that thing weep like you were burying your Mama or he could make that thing praise the goodness of the Lord. He made the blues harp become like a saxophone, where he could produce cool mellow moods or hot screams and shouts. No one on the harp could do what Walter could do.

I could walk right out my back door and be at Little Walter’s back door in fifteen seconds. He worked a lot on the road but was never gone too long. He’d be out there four days, then back home for three. Sometimes he went farther and would be gone for a week or more. But most times he was at home, especially Tuesdays and Wednesdays. From the time I first saw Walter onstage with Muddy Waters, I knew he was something. Now, as neighbors, I saw him in full bloom. He had some money and dressed like somebody. He had a lot of hats and suits! Mane, he had beige, brown, gray, pinstripe—black. Between that slicked-back conk hair and reddish-brown skin, he was a handsome cat when he wanted to be.

Little Walter was nice to me. But he was a complicated man. He was a little guy, and maybe he had what they call a Napoleon complex. If he felt you were above him in any way—education-wise, socially, had a cuter girl, anything—he’d have a problem with ya. He was like a guy who couldn’t read or write thinking everybody was writing bad things about him.

He’d always start some kind of rumble. Something was never right. I’d walk to his back door many mornings, knock, and say, “Hey, let’s grab some grub.” We’d go to some hash house, and he’d be in good spirits. We’d be laughin’ or talkin’ ’bout music or women. But it wasn’t long before something wasn’t right. Eggs weren’t right, bacon wasn’t hard enough, coffee wasn’t hot enough. Just penny-ante stuff. It got so bad that if the toast wasn’t right, I’d say, “Aw, come on, Walter, take my toast.” It was like you were always putting out these fires over absolutely nothin’. It was hard for people to understand how someone like Little Walter—with so much talent, handsome as the devil—could be so touchy. But he was.

I didn’t shun Walter. Why? Because he was Little Walter. A living legend on the harp. And I was Bobby Rush, still trying to make a record and get people to take notice of me outside of Chicago. With the success of his hit record “Juke,” Walter had left Muddy’s band. Muddy said nothing to me personally about whether he was pissed at Walter, but all I know is that even after he left Muddy’s band, Walter still played on just about everything Mud recorded in the studio.

I, on the other hand, was trying to get my own record deal. It would take some time, but at least I had gigs. And sometimes I had more gigs than folks who had records. I hustled hard.

“Bobby, what’chu doin’ tonight?” Walter said.

“Ah, mane, I ain’t doin’ nothing—but you know me. That means I’ll be doin’ something.”

“Man, come on wit’ me to Waukegan—got a nine o’clock gig at the Cat and Fiddle.”

“Cool. Leave ’round seven?”

“Naw, ’round three thirty.”

“Why so early?”

“Man, I wanna cat around a little.”

“A’ight—I’m in.”

I may have had five dollars with me. Walter had a pocket full of money. He probably only had thirty dollars, but it was all in ones—so it looked like a wad to me. And frankly, thirty dollars was a lot of money to me anyway. As Walter and I walked into the joint around five, the girls were there already and, mane, they were something else. All kinds of beautiful sisters of every color dressed to the nines, hair all done up. Fine, fine, fine.

Walter said, “This is my little brother, Bobby.” “Ah, he’s cute,” one of the ladies said. Walter ordered three quarts of beer for everybody—then another round, and before you knew it the girls were sitting on my lap, drinking, rubbing my hair, and kissing on me, just like they were stuck like glue to Walter.

I was having the absolute time of my life!

Now remember, I ain’t drinkin’, but I might as well have been ’cause my head was spinning from all the affectionate attention I was receiving. The voice in my head said, Damn, Walter, you really are a superstar.

Walter said, “Man, I almost outta money.” I thought, No, no, no, Walter, not now. Please not now. I’m enjoying the hell out of this scene here. But he said, “Let’s go,” and with my nature looking like a big top tent through my pants. I was thinking we would drive back to Chicago. But he walked around to the rear of the car, popped the trunk of his Caddy open, and it was a mountain of money. It was all in one-dollar bills, so it probably wasn’t more than $500, but it was just loosely laying there in the trunk—it looked a million dollars to me. It just blew my mind—all that money. I even forgot about the girls!

Little Walter

Gilles Petard/Redferns/GettyHe said, “Get you some.” So being polite and not greedy, reaching down I grabbed one fistful. Couldn’t have been more than twenty dollars or so. Walter was so drunk that when he slammed the trunk, some of the loose bills stirred up in the blast of air and they got stuck between the trunk and car body. They’re sticking out of the seams like confetti. So I pulled out the ones I could and stuck back in the ones that could be pushed. I was plucking and pushing those bills like a thirsty man in the desert looking for water.

As we were walkin’ back to the club, I was thinking: Walter’s got to be selling dope. Ain’t no way he’s making money like that playing music. So I just straight out asked him, “Walter, how you git all dis money?” He shot back without missing a beat, “Blowin’ harp, maaannnnnn. Blowin’ that harp. I’m a harmonica player!”

The pride in his voice even with the liquor came through: “I’m a harmonica player!”

Stood out to me. And so did the money.

Around this time I was playing a lot of guitar and bass. But after that, I really started to blow the harp on more songs and with more gusto. I felt the power of it—I also thought about that pile of money. Little Walter was a rock star. Crazy, yes. Hot-headed for sure. Warm when he wanted to be. Definitely. Most folks rightfully say he’s the Jimi Hendrix of the harp—pulling out unique sounds of the harmonica nobody had heard before; and that’s true. It’s also true he lit my fire.

Excerpted from I AIN’T STUDDIN’ YA: My American Blues Story by Bobby Rush, with Herb Powell. Copyright © 2021. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.