It's one of the U.K.’s greatest and most enduring mysteries—and last night it came one step closer to finally being solved.

For Britons, the Lord Lucan scandal still holds an extraordinary fascination, even though the events occurred well more than three decades ago. It centers around a murder that went horrifically awry, and one of Britain’s most dashing peers, the seventh earl of Lucan, who disappeared off the face of the earth after the crime and has not been seen since.

Now, for the first time, the earl’s brother Hugh Bingham has broken his silence to reveal that Lord Lucan escaped to Africa—and may well still be alive. It is the only time that the Honorable Hugh Bingham, 72, has ever spoken about the murder, and it gives us a tantalizing glimpse into what may genuinely have happened to Lord Lucan.

Asked by the London Mirror if his brother had escaped to Africa, Bingham said from his home in Johannesburg, South Africa, “I am sure he did, yes. But what connection there is I don’t know.” He added: “I wouldn’t like to form an opinion as to his whereabouts today or whether he is alive or dead. The last time I had contact with my brother was a long, long time ago before the incident, lost in the mists of time.”

The Hugh Bingham interview comes on the heels of yet further evidence this week that the earl’s multimillionaire friends helped him escape to Africa. But although there is every indication that Lord Lucan did just that, his final whereabouts remain as much of an enigma as they always have been. No bones have yet been discovered, no diaries found, and the two men who almost certainly effected his escape have taken the secret to their graves.

The scandal is little known outside the U.K., but in Britain, it still resonates with huge power: the popular "red top" Daily Mirror devoted the first five pages of Saturday’s paper to its interview with Bingham.

The very name “Lord Lucan” has now entered the English lexicon as slang for anything farfetched or simply unbelievable. His sudden disappearance in 1974 has all the fairy-tale quality of a modern-day Rip Van Winkle. And ever since, the world has been speculating as to his whereabouts—in the last 38 years, the earl has been spotted all over the world, from South America to India to Alaska.

There has also been the theory—widely promulgated by many of the earl’s friends—that he committed suicide soon after the murder. But with all evidence currently pointing to Lucan having fled to Africa, the years of talk about suicide now merely sound as if the earl’s friends were doing their best to muddy the water.

The night that was to change not just the life of Lord Lucan but that of his entire family was Nov. 7, 1974. The ripple effect of the earl’s botched murder was profound and has devastated his entire family. They also led to the suicide of one of Lucan’s closest friends, Dominic Elwes, and, bizarrely, prompted the arrest of Britain’s former postmaster general, John Stonehouse.

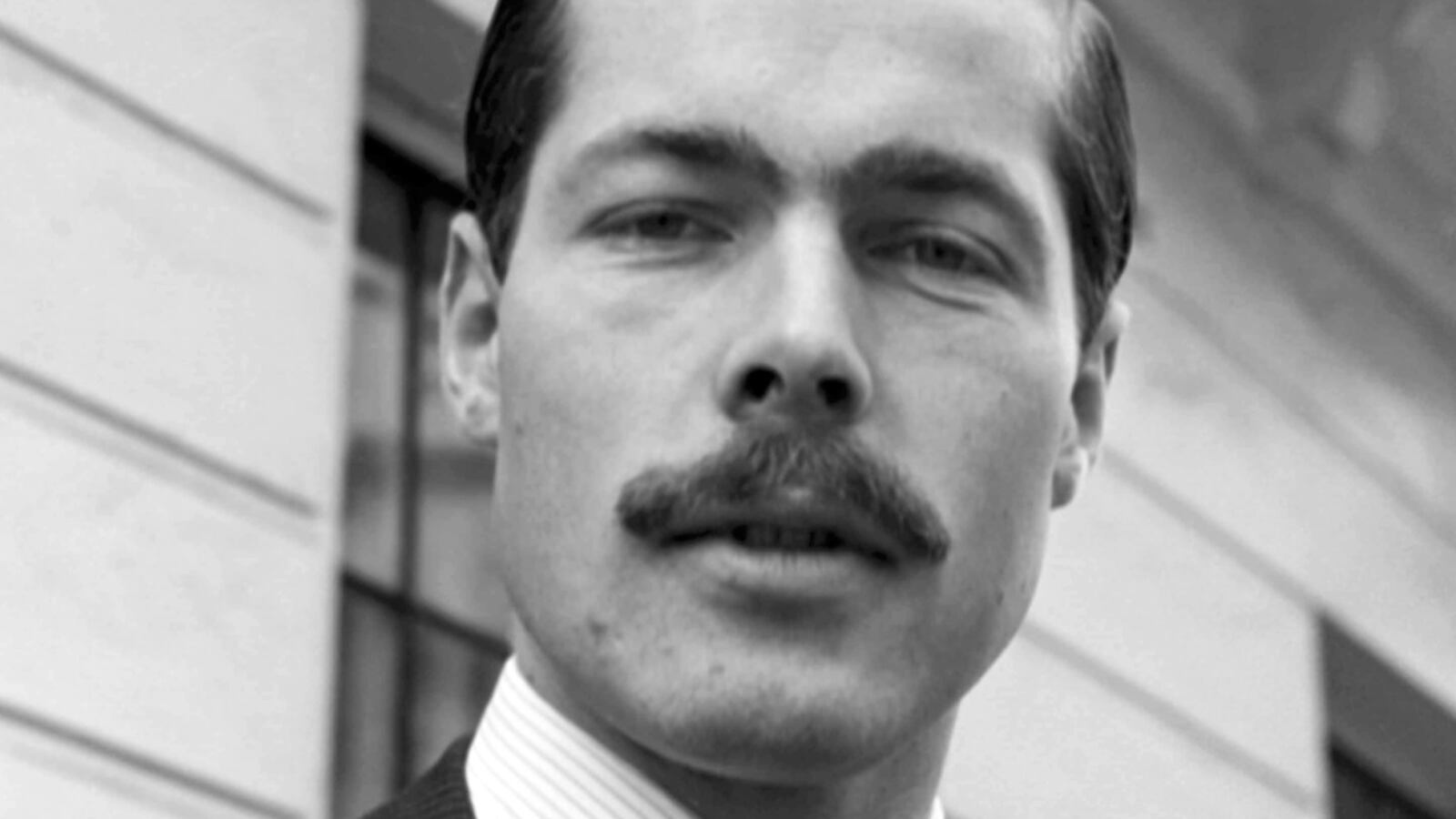

At the time, the earl was 39 years old and, with his trademark mustache, a very handsome professional gambler who enjoyed driving power boats and fast cars. But although his dapper features were frequently seen in the society pages of glossy magazines, his life was clearly going off the rails. He was nearly bankrupt after losing most of his fortune to his so-called friend John Aspinall at the Clermont Club.

That Aspinall was a scoundrel and a cheat became common knowledge after he died of cancer in 2000. He used his casinos and his top-notch connections to fleece many of Britain’s leading aristocrats, including Lord Lucan. It is now known from books such as Douglas Thompson’s The Hustlers that Aspinall was in league with a group of London mobsters. While Aspinall provided the wealthy clientele, the mobsters provided a coterie of highly skilled cardsharps.

Aside from losing his vast fortune to Aspinall, Lucan was also estranged from his wife, Veronica. She lived with Lucan’s three children—George, Camilla, and Frances—in Belgravia, West London, while Lucan lived in a flat nearby.

All these circumstances seem to have driven Lucan over the edge.

Here's what allegedly happened: The earl planned to sneak into his old home and wait for his wife in the downstairs kitchen, where he would bludgeon her to death with a piece of lead piping with white tape wrapped around it as a grip. Lucan also borrowed an old Ford Corsair from a friend and planned to take the body to Newhaven, Kent, where he was going to dump it in the sea from his boat.

Lucan had supposedly everything planned right down to the last detail, including various alibis who were supposed to be dining with him later in the evening. But the one thing he had never conceived was that his children’s nanny, Sandra Rivett, would change her night off. Sandra, 29, had only been with the family for six weeks and, like the countess, was a petite woman.

Again, it should be reiterated that nothing is known for certain about what happened on the night of the murder, but Lucan had taken out the kitchen light bulbs and had been lying in wait at the bottom of the stairs. When he saw this petite woman coming into the kitchen, he attacked her, raining at least six or seven blows onto the back of her head.

It appears that he was trying to stuff Sandra’s body into a mail bag when he was disturbed by the countess. The couple had a fight on the stairs, in which he once again struck out with the lead piping, but she caught him with a low blow to the groin.

After the fight, the pair allegedly managed to hold a short and moderately civilized conversation on the stairs before Lucan went to wash off the blood. While he was still in the bathroom, the countess took her chance and escaped, and ran screaming and drenched in blood into the nearby Plumbers Arms pub. She named her husband, Lord Lucan, as the attacker.

As to the rest of what happened to the Earl Lucan, very little is known. He called up his mother, the dowager countess, and asked her to come over and look after the children. He then drove hell for leather to Uckfield, Sussex, where he had some whiskey with his friend Susan Maxwell-Scott. She was the last person ever to admit to seeing him alive.

While Lucan was in Uckfield, he wrote a few letters to friends in which he came out with his own version of events: he said that he had been walking past the basement when he’d seen an intruder attacking Sandra Rivett.

To his brother-in-law Bill Shand Kydd, he wrote: “The most ghastly circumstances arose last night, which I have described briefly to my mother, when I interrupted the fight in Lower Belgrave Street and the man left.

“V accused me of having hired him. I took her upstairs and sent Frances to bed and tried to clean her up. I went into the bathroom and she left the house.

“The circumstantial evidence against me is strong, in that V will say it was all my doing and I will lie doggo for a while, but I am only concerned about the children. V has demonstrated her hatred for me and would do anything to see me accused.”

After writing his letters, Lucan left the Uckfield house at 1:15 a.m. and drove 16 miles to Newhaven, where he dumped the Corsair. And for a man who so meticulously planned his wife’s murder, he made one small but catastrophic error that would torpedo any of his bogus arguments.

In the trunk of the Corsair was a piece of lead piping with white tape wrapped around the outside; it was nearly identical to the actual murder weapon that had been left at the scene of the crime—proof positive that the earl was up to his neck in the murder.

In the ensuing 38 years, the police and the British press have trawled the earth in search of Britain’s most wanted fugitive. Thirty years ago, newspaper editors would think nothing of spending tens of thousands of pounds on tracking down the latest elusive tip on the earl’s whereabouts.

In journalistic terms, the scandal has become the Moby Dick of exclusives, a huge story that would ensure fame and glory for any journalist who managed to crack it. The new Sunday Sun, which is being launched in Britain tomorrow to replace the now defunct News of the World, is said to be running with a Lord Lucan exclusive for its first-ever front page.

But although there have been many tips and many books on the earl and much wild speculation, no one has ever produced any concrete evidence as to what actually happened to the earl.

And so far, every time that a journalist or an author has definitively claimed to have found out what happened to him, they have consistently ended up with egg on their faces. The most famous example of this came in 2003, with the publication of Duncan MacLaughlin and William Hall’s book, Dead Lucky—Lord Lucan: The Final Truth. Within hours of The Final Truth hitting the bookshelves, it was revealed that the man they had tracked down to India was not Lucan, but a loner called Jungle Barry.

Genuine facts, then, are in very short supply when it comes to guessing what happened to Lucan. But there a few things that we do know, and the first is that he was a gambler. His friends called him “Lucky.” He particularly loved playing bridge and backgammon, and he was certainly not the sort of man to throw in his cards just because he had been dealt a dud hand.

It is true that many of his friends say that he committed suicide. They have come up with myriad reasons for why Lucan killed himself, including that he couldn’t take the shame, that he couldn’t take not being with his children, and slightly farfetched, that he was a creature of habit who wouldn’t be able to survive outside Britain.

But all the evidence in Lucan’s character points to him seeing it through to the bitter end. The other facts that we know are the characters of Lucan’s friends, particularly John Aspinall, the owner of the Clermont Club, and Sir Jimmy Goldsmith, the multimillionaire businessman. Now it is true that these two men are now dead, and so cannot readily defend themselves, but it would be fair to describe them both as absolutely unscrupulous rogues.

So when it came to the wire, Aspinall and Goldsmith would have seen their friend right, whatever the consequences. Aspinall himself said on many occasions that Lord Lucan was his friend, and that he would stand by his friends to the last. The mere fact that Lucan was wanted for murder would not even have registered on the scale with Aspinall and Goldsmith; it is actually much more likely that the pair would have reveled in stonewalling the British police.

Aspinall and Goldsmith definitely had the means and the motive to help Lucan flee. But what's much more important is that they also had the low-life contacts to get Lucan out of the country, as well as enough money to ensure that he could set up a new life in Africa.

The real tragedy of Sandra Rivett’s murder—apart from the devastation that it has caused to her family and friends—is the huge shadow that it has cast over the lives of Lucan's wife and his three children. It is almost as if Lucan’s family have come to be defined by that one bleak night in November 1974.

The countess had a mental breakdown in 1982 and lost custody of her children, who went on to live with their uncle and aunt in Buckinghamshire. Now 72, she is no longer on speaking terms with her children, and still seems to be obsessed by the murder. On her website, she goes on the record with her views about the murder, and in her home in Mayfair, London, there is still an oil painting of Lucan hanging on the wall.

As for the earl’s children, his two daughters have managed to stay relatively under the radar, but his son and heir, George, 44, cuts a lonely and eccentric figure. George is unmarried and remains just plain George Bingham. He has never been tempted to take the title that is his right and to become the eighth earl of Lucan—because he is fully aware that, across the country, the very name “Lord Lucan” has been turned into a laughingstock.