On March 12, 2007, an obscure congressman from Texas announced his run for the Presidency of the United States. He was a fringe candidate running on the Republican ticket with little hope of winning a primary, let alone the nomination.

Then—suddenly—Ron Paul was everywhere.

Within a few months, Paul landed a spot on Real Time with Bill Maher, thanks to unprecedented online momentum that would capture the attention of the mainstream press.

Wired magazine detailed how Paul was taking over the web. The Washington Post ran the numbers, noting he was more popular on Facebook than his GOP primary rival John McCain, had more friends on MySpace than Mitt Romney, and garnered almost as many views on YouTube as Barack Obama (while also noting Paul’s low polling numbers.) Other outlets also highlighted the mismatch between real world and online popularity—such as the NBC News story, “An also-ran in GOP polls, Paul is huge on Web.”

When it came to online polls, however, Paul would win consistently and by a large margin—something that came to be known as the “Ron Paul Effect.”

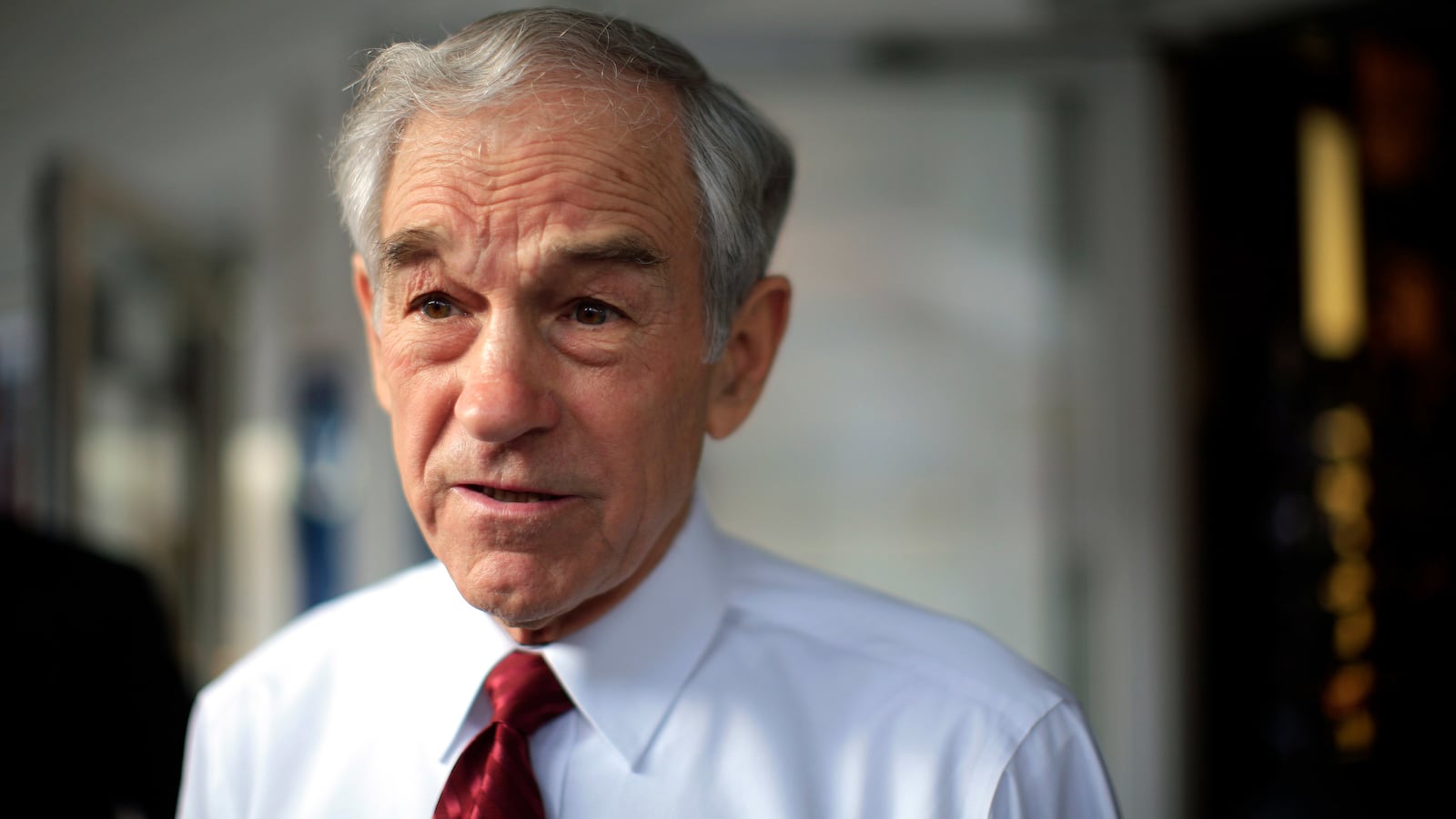

Republican presidential hopeful Congressman Ron Paul (R-TX), greets supporters following The Des Moines Register Presidential Debate December 12, 2007 in Johnston, Iowa.

Scott Olson/Getty ImagesCNN’s Jack Cafferty observed Paul’s followers “at any given moment can almost overpower the internet,” something that had a Pavlovian effect on editors, who’d try to include his name wherever possible because it guaranteed a flood of traffic. The momentum continued through 2007, driving record online fundraising and eventually leading to Time magazine giving him the moniker “Candidate 2.0.”

The narrative that grew around Paul’s candidacy was that he was the product of the internet and Web 2.0—a presidential hopeful free from the clutches of establishment media gatekeepers.

Some, however, had doubts about the authenticity of Paul’s momentum.

Users of Reddit and Digg complained that bot activity was pushing Ron Paul stories to the front page, while downvoting anti-Paul comments and submissions (such as reports on his racist newsletters).

A number of editors grew tired of the “Ron Paul Effect,” which they saw as obvious online manipulation. One CNBC editor wrote an open letter to Ron Paul supporters explaining why he was forced to take down an online poll that was being overwhelmed by votes for Paul. Henry Blodget of Business Insider also complained of being flooded with bot activity. And RedState.com instituted a ban on Ron Paul supporters creating new accounts outright, for similar reasons.

Paul boosters saw this as part of a larger effort by the establishment media gatekeepers to suppress Paul’s candidacy and delegitimize his movement. If it was, it failed.

In late October 2007, Paul landed a primetime appearance usually reserved for mainstream presidential candidates: The Tonight Show with Jay Leno. He reached millions of new voters, but the following day the very online momentum that propelled him there would be revealed to have been partly the work of a botnet.

Ron Paul’s campaign manager, Jesse Benton, while en route to the Jay Leno taping, sent an email to a reporter seeking comment about an investigation exposing a Ukrainian botnet that had sent almost 200 million pro-Ron Paul spam emails—throwing the authenticity of his online momentum into question. The reporter asked for a comment on the story. Benton, in reply, blamed enemies of the campaign who were trying to invalidate Paul’s grassroots rise.

The following day, Wired’s effusive coverage of Paul turned sour, stating: “If Texas congressman Ron Paul is elected president in 2008, he may be the first leader of the free world put into power with the help of a global network of hacked PCs spewing spam.”

The Guardian, Fox News, ABC News, and many other mainstream outlets covered the story too. The “Ron Paul Effect” suddenly seemed like a mirage.

However, Benton’s explanation gave plausible deniability, and Paul’s record online fundraising was a proof point that he had a meaningful groundswell of real human support. The Ron Paul Revolution’s reputation and legacy, survived.

Jesse Benton, spokesman for the Ron Paul campaign, speaking to reporters in the spin room after the CNN Debate on January 1, 2012.

Robert Daemmrich Photography Inc/Corbis/GettyThe recent news that Jesse Benton has been convicted of funneling Russian money to support Donald Trump (who pardoned him for his involvement in nefarious campaign activities during Ron Paul’s 2012 campaign) has presented an opportunity to take a second look at the “Ron Paul Revolution”—and a number of unreported and under-reported facts.

The botnet which sent the spam would later be linked to Russia, after first being traced to Ukraine. When it was taken offline in 2008, The Washington Post reported “unknown individuals in Russia eventually gained control over the botnet,” citing security research firm FireEye, who also noted one of its SMTP servers was found pointing to a Russian state-owned bank.

It turns out not only were Ron Paul’s online fundraisers bolstered by promotional spam emails, they were juiced with foreign donations from numerous stolen credit cards—something that received limited coverage at the time. Benton dismissed this development as merely credit card thieves testing cards—a common tactic—and once again, offering plausible deniability.

The deniability is less plausible when you realize the stolen credit cards all came from a bank in Paul’s home state of Texas, and the donations and the spam happened in the same period between October 24 and October 27—signaling what could potentially have been a much more coordinated and illegal effort to help Paul.

It also seems the botnet helped drive the very online momentum that got Paul mainstream attention. YouTube later removed videos that were boosted by spam emails, other spam emails surfaced which linked to online fundraisers, polls, and even early references to a “tea party” movement.

As campaign manager, Jesse Benton went on to help Ron Paul’s son—Rand Paul—win a U.S. Senate seat out of Kentucky in 2010. And Benton was back with Paul the elder in 2012, when he ran his next presidential campaign. RT (the Russian state-sponsored English-language network then known as Russia Today) heavily promoted fundraisers for Ron Paul, which led to the network being sued for a Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) violation.

Jesse Benton arrives for his sentencing hearing at the federal courthouse in Des Moines, Iowa on September 20, 2016.

David Pitt/AP/ShutterstockBenton was convicted in 2016 of bribing an official to give an endorsement to Ron Paul, for which he was pardoned by President Trump in December 2020. And now he’s been convicted again, this time for funneling Russian money to Trump.

The person in charge of Ron Paul’s data operations at the time was a man named Nick Spanos.

During or around the time he worked for Paul’s 2008 campaign, Spanos posted photos and comments to Facebook indicating his involvement with an event in the U.S. honoring former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. (Editor's Note: Spanos responded to The Daily Beast's request for clarification after this piece was published, stating that he was a long time volunteer event organizer for the Greek Orthodox Church, and while he helped organize the event, was not a member of Mikhail Gorbachev's security detail. Gorbachev was being presented a humanitarian award.)

Spanos eventually moved into the world of crypto-currency and, in 2017, was part of a meeting with Nicholas Maduro about Venezuela’s crypto-currency project, the “Petro.” At a conference related to the project, Spanos spoke with the press and detailed how the project would work on a technical level. Then, he later implied he thought the whole thing was a bad idea to The New York Times, saying, “I didn’t think I’d see this kid again.”

Days before Spanos arrived in Venezuela, he appeared on Russia Today to debate crypto-currency. The Petro project would later be revealed by Time magazine to have been heavily shaped by the Kremlin and signed off on by Vladimir Putin, as a way to undermine U.S. sanctions.

Ron Paul left office in 2013 and started the Ron Paul Institute. Among its board members are John Laughland, a founding member of the Institute for Democracy and Cooperation, a pro-Russian think tank that was announced by Vladimir Putin on October 26, 2007, the very same day stolen credit cards were used to donate to Ron Paul and over 100 million spam emails were sent out.

In retrospect, it seems likely Ron Paul’s presidential campaign was also part of an early experiment in cyberwarfare by the Kremlin—something it actively ramped up in 2007 in Europe. Whether you believe this involved “collusion” or not, it is hard to look at all of the preceding entanglements between Paul’s political movement and Russia as merely a whole lot of “coincidences.”