One day in September, 1890, a Frenchman named Louis Le Prince boarded a train in Dijon, headed for Paris. Two years earlier Le Prince, a former chemist and industrial draftsman, had shot the world’s first motion picture, a two-second snippet of some family members gamboling around a garden in Leeds, England, where they then lived.

That was three years before Thomas Edison announced his Kinetograph, a motion picture device similar to Le Prince’s, and seven years before the Lumière brothers held the first commercial showing of a motion picture.

Despite this, Le Prince’s contribution to cinema history has been mostly lost in the mists of time. Because on that day in 1890, in debt and plagued by competitors who included the already legendary Edison, Le Prince didn’t get off the train in Paris; he simply disappeared, never to be seen or heard from again.

Did Edison have his competition killed? Was it suicide? Or did Le Prince's brother Alfred, who owed him a lot of money which he couldn’t repay, murder him? Paul Fischer, author of The Man Who Invented Motion Pictures: A True Tale of Obsession, Murder and the Movies, opts for the latter, claiming that because Alfred never reported his brother missing, lied about efforts to find him and discouraged his wife—who was living in America at the time—from coming to look for him, he was the killer.

“[Le Prince] left no letters or writings suggesting he might end his life,” says Fischer, “his colleagues and family saw no despair in him, and he had made plans for the future, including travel to New York to unveil his invention.”

Le Prince film of a garden scene in Leeds, Yorkshire, October 1888.

Science & Society Picture Library/Getty ImagesThe mystery of Le Prince’s death is not, however, the most interesting element in Fischer’s book, which is an exhaustively researched look into not only the Frenchman’s life, but the history of photography and the attempts to move from visual still lifes to actual motion. “I hope [the book] helps us think in different ways about what cinema was when people were inventing it,” says Fischer. “The only questions they had were—does it move? Do you believe it? Will it hold people’s attention? Is it life?”

In order to tell this story, Fischer’s book is filled with names that have become legendary in photography and motion picture history: Louis Daguerre, one of the fathers of the photographic process; Eadweard Muybridge, who was the first to take photos that froze movement (prior to this, subjects had to remain motionless for a period of time so their photo could be taken); George Eastman, founder of the Eastman Kodak Company, whose Kodak camera, with spools of paper coated with emulsion, replaced glass plates and were a major breakthrough; and the lesser known John Carbutt, who perfected celluloid film, which Eastman then introduced on rolls for his cameras.

All of these men benefited from an era, roughly spanning 1840-1890, that saw enormous advances in technology, and the invention of photography, the telegraph, the steam engine, anesthesia, the telephone, the electric light and more. Fischer claims a lot of this rapid tech advancement was “incentivized by the law, in the form of patents. If you could show you had invented something—if you could show you came first—you could patent that invention, and no one else would be allowed to make money from it without your permission. So now, each advancement drives the next advancement, because it opens up a whole new field of potential further advancement, and every one of those advancements means cash.”

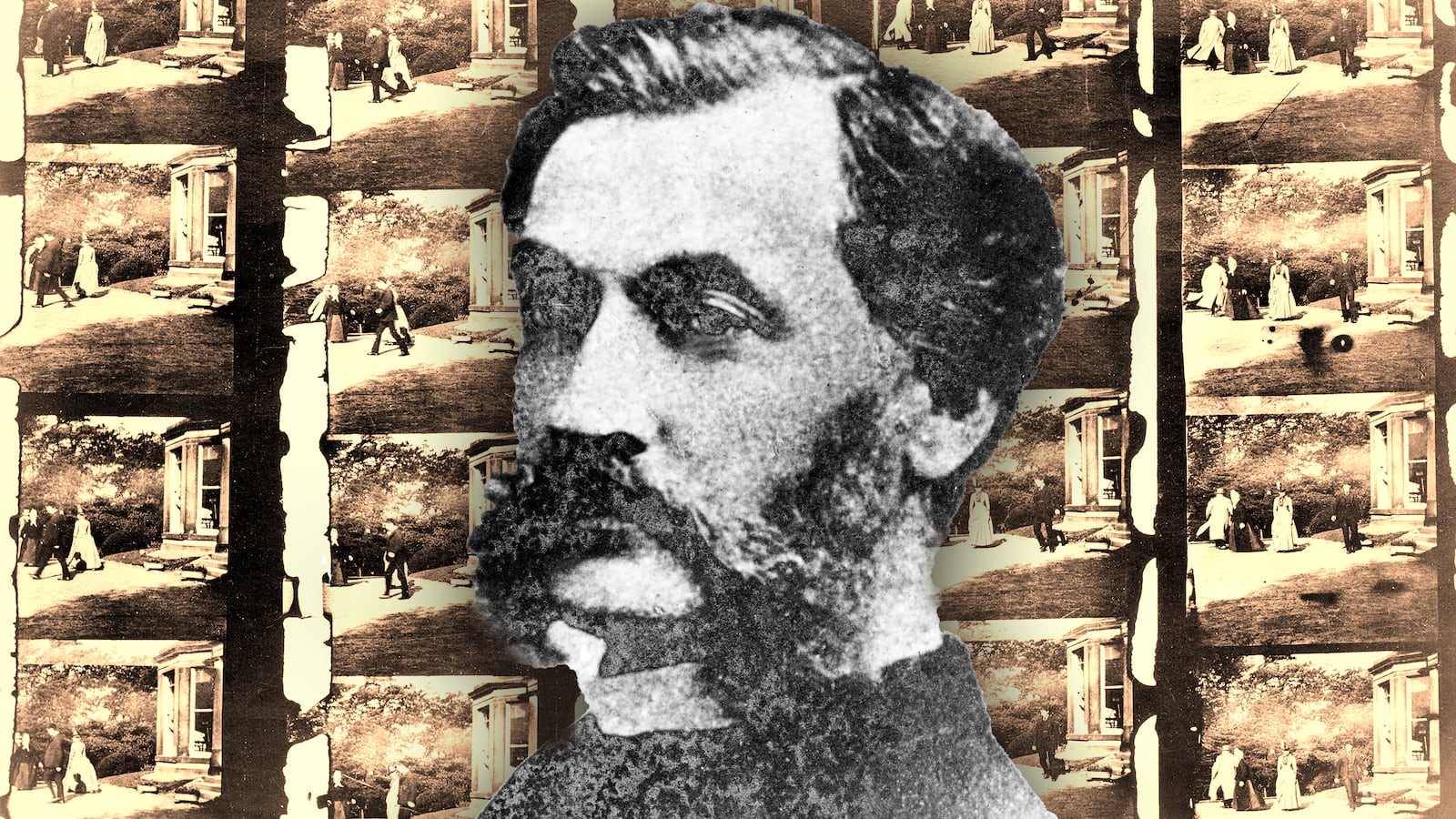

French inventor and filmmaker Louis Le Prince, right, with his father in-law, Joseph Whitley, at the Whitley family home in Roundhay, Leeds, Yorkshire, 1887.

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesAlthough The Man Who Invented Motion Pictures goes into great, sometimes exhausting, detail surrounding the technological advances that made motion pictures possible, it is the story of who eventually got credit for the invention, and the legal issues surrounding it, that has the most contemporary resonance. And that’s all about Edison, who comes off as a combination of Donald Trump and Steve Jobs, a man who in many ways was the 19th-century version of a modern tech company leader who also used gaps in the legal system to beat the competition.

Edison was a big fan of the caveat, a sort of prepatent, in which an inventor declares their intention to file a full submission soon. This could be used to establish priority over a device, and helped someone like Edison snuff out rivals. If a rival applied to certify a similar process, the Patent Office put it on hold, notified the caveat holder, and gave them three months to file a formal application. Edison used the caveat 120 times.

So even though Le Prince was the first to design film reels and a camera and projector with a single lens each, thus abandoning the use of glass plates, his advances were, thanks to Edison’s sophisticated—some would say amoral—use of the patent laws, pretty much nullified.

“A lot of the nefarious stuff that can be associated with Edison isn’t very different from the practices of large corporations today,” says Fischer. “He disparaged the competition and sometimes stole from them and often sued smaller rivals into the ground. He exploited the patent system in a way not too dissimilar to the way a company like Disney uses its own weight to exploit copyright law to its own advantage.”

Yet the historical record is what it is: That short snippet shot by Le Prince, now known as the Roundhay Garden Scene, is inarguably the oldest motion picture footage, and it is, says Fischer, a peek into what he sees as the inventor’s intentions and hopes for the new technology.

“The first words that came to mind when I watched the Roundhay Garden Scene were ‘home movie,’” says Fischer. “I think that’s one thing I really love about it. Le Prince really seemed to think of film first and foremost as something that would connect people and would preserve memories and would allow us to relive our loved ones even after they had gone. The [scene] really struck me because it has that innocuous, everyday quality.”

Fisher says this to contrast Le Prince’s film with the early work of people like Edison and the Lumière brothers, who “were predominantly making little skits that could showcase the novelty value of their inventions,” by filming such things as a crowd leaving a factory or a train rushing towards the viewer. “Le Prince knew spectacle was important,” says Fischer. “His early ideas for filming subjects included the circus and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. But for that first film, he chose to film his family doing silly walks around the garden at home.”

This camera made by Louis Le Prince took a series of pictures using 16 independent shutters, fired in sequence.

SSPL/Getty ImagesAnd that was it for Le Prince. Years after he disappeared, Edison won the patent wars and with other companies formed a monopoly, which demanded licensing fees from all producers, distributors and exhibitors. That forced the independent producers of the day to flee the East Coast and settle in the new town of Hollywood. Would things have been different if Le Prince had been alive?

“If Le Prince had lived and retained control of his invention, maybe there’s no Hollywood,” says Fischer. “Maybe the ecosystem for independent filmmaking would have been healthier, because Le Prince seems to have wanted his film camera to be widely available, the way photo cameras were. [Or] it might not have been very different at all, except maybe kids would learn about Louis Le Prince at school, and maybe the cinema world would’ve remained in New York a little bit longer.”