Where do you live?

I moved to London 12 years ago, to live with [my partner and translator] Flora Drew, whom I met in Hong Kong on the night of the [1997] handover. Until recently, I would spend many months of every year in Beijing. For the last two years, however, I’ve been refused entry into China, so I am now a genuine exile. London used to be a refuge I returned to, in order to write in freedom. Now, it has become a place of banishment.

If you can imagine a world in which the Cultural Revolution had not taken place in China, do you think that you would still have become a painter and a writer?

The Cultural Revolution was not the only calamity to convulse the China of my youth—there was also the Anti-Rightist Movement and the Great Famine. All these events affected me deeply. Whatever China I’d been born into, I would probably still have become a painter—I loved sketching portraits as a child, and began art classes at the age 7. But if China hadn’t been under Maoist rule, I might never have become a writer.

How did you shift from being a painter to a writer?

In my 20s, when I was a photojournalist in Beijing, I joined an underground art group, and put on clandestine exhibitions of my paintings. It was the early ‘80s, and China was just beginning to open up. But in 1983, the Communist Party launched a Campaign against Spiritual Pollution, to clamp down on experimental art. The police ransacked my home, confiscated my paintings, and placed me in detention. When I was released, they warned me that if I didn’t mend my ways, they could make me disappear. I lost interest in painting after that—it was an art form too open to misinterpretation. I gave up my job and took to the road. Three years later, I returned to Beijing and wrote my first novella—Stick Out Your Tongue, inspired by my travels through Tibet. Writing, I discovered, allowed me to express more deeply and clearly my view of the world.

Do you recall your first reaction to learning that Stick Out Your Tongue had been denounced, confiscated, and destroyed?

While I was writing Stick Out Your Tongue in Beijing, the police began knocking on my door again. As soon as I finished the book, I moved to Hong Kong, so that I could work undisturbed on my next novel. One day, while I was living in a bookshop in Wanchai, I turned on the television and saw, to my astonishment, a clip from Chinese state TV announcing that my book had been publicly denounced, and that all copies were to be confiscated and burnt. I knew at once that this was the end for me: my writing career in China was over.

It was brave and noble of you to establish New Era and Trends, venues to publish works that had been banned in China. What led you to establish these projects and were you concerned for your safety in doing so?

After the Tiananmen Massacre, I felt compelled not only to continue writing but to actively resist the restrictions placed on freedom of speech. I set up the publishing company in Hong Kong, with offices in Shenzhen in mainland China, and managed to publish works of fiction, philosophy, and politics by unapproved authors. But in 1995, I went a step too far and published a memoir by an illegitimate son of Chairman Mao. My Shenzhen offices were closed by the police and the company’s bank accounts were frozen. So that was the end of that.

Describe your morning routine.

My mornings are always a blur. Flora and I have four young children, so I write late into the night—the only time our home is silent. At three in the morning, I usually collapse on the narrow bed in my study, but am often woken a couple of hours later by one or both of our 3-year-old twins, who like to waddle down from their room and climb on top of me. At 8, I make pancakes for the children, then sleep again until 11. This is when the day really begins. I make myself a cup of tea, sit at my desk, phone my friends in Beijing, read for a while, then start thinking about what I am going to write.

What is a distinctive habit or affectation of yours?

I have few habits, but one thing I can’t do without is green tea. Now that I can’t return to China, I ask my friends to bring me new supplies whenever they visit.

Please recommend three books by Chinese authors that your readers might enjoy, but might not know about, and tell us why you like them.

Strange Tales of Liaozhai, by the Qing Dynasty author Pu Songling. Wonderful supernatural stories in which the ghosts, demons and fox spirits are kinder and more humane than the human characters.

China 1957, by You Fengwei. A powerful novel describing Mao’s persecution of China’s intellectuals.

Border Town, by Shen Congwen—a beautiful evocation of rural China in the 1930s.

Describe your routine when conceiving of a book and its plot, before the writing begins. Do you like to map out your books ahead of time, or just let it flow?

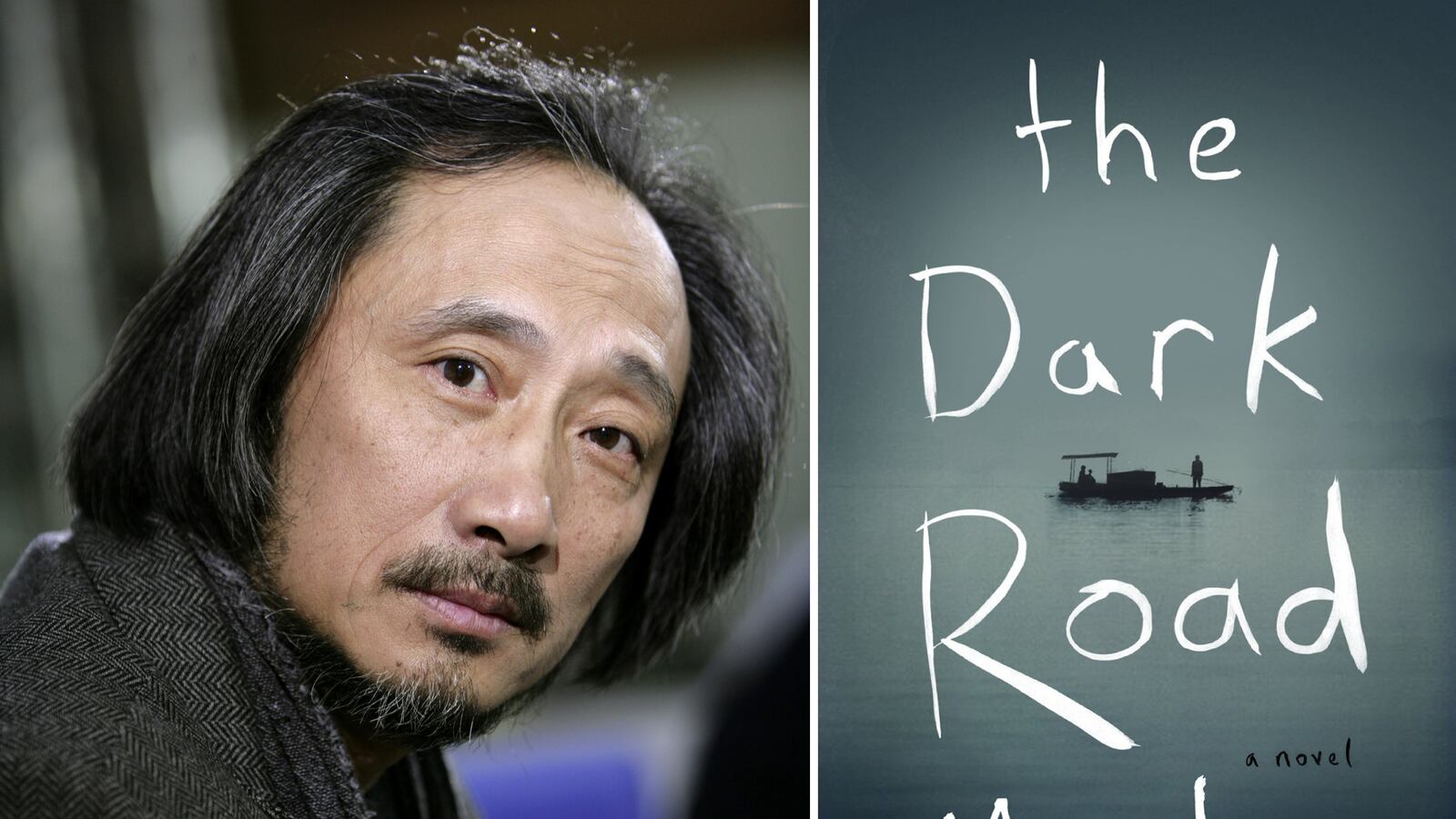

Each of my books begins as an image I can’t get out of my mind. For Beijing Coma, it was a sparrow perched on the body of a comatose man; for The Dark Road, it was a pregnant woman floating down the Yangtze in a dilapidated barge. Slowly, themes and ideas emerge. I paste my walls with maps, drawings, lines of poetry, and sketch out a vague structure. After the first draft, I like to travel to the places in the book, to absorb the rhythms of the local speech and the colours of the landscape. By the third or fourth draft, my characters take control of the novel, and it is they who decide how it will end.

What is your process like with your partner, Flora Drew, when she is translating one of your books?

At the beginning, I answer her many questions, and we have long, detailed discussions. By the end, when she’s struggling to meet deadlines, my role is merely to bring her cups of tea and chocolate.

Is there anything distinctive or unusual about your work space? Besides the obvious, what do you keep on your desk? What is the view from your favorite work space?

My study is a book-lined room on the first floor. During the day, the children often wander in to distract me from my work, or to draw pictures on a small table set up for them in the corner. I try, in vain, to keep my desk clear of clutter. The window looks out onto the overgrown weeds and an abandoned pool table in our neighbor’s garden.

What is guaranteed to make you laugh?

The unanswerable questions my twins often ask me, such as, “Dad, why is your ear here?”

What is guaranteed to make you cry?

The many assaults on human dignity that I have witnessed in China.

Do you have any superstitions?

I have grown more superstitious with age. As 2013 is my Chinese zodiac year, which is traditionally believed to be inauspicious, I am wearing holy beads around my wrist to ward off evil spirits.

What is something you always carry with you?

I always carry a pen, notepad, and a pocket torch.

If you could bring back to life one deceased person, who would it be and why?

My mother. She became terminally ill last year, but all my requests to return to China to visit her before she died were refused. When I heard she only had days to live, I flew to Hong Kong and pleaded with the border guards to let me through, but I was turned away. A few weeks later, after many appeals, I was given special dispensation to return briefly to my hometown to bury her ashes.

Tell us something about yourself that is largely unknown and perhaps surprising.

I like baking sponge cakes and macaroons.

What is your favorite snack?

Chinese dates and roasted sunflower seeds.

What advice would you give to an aspiring author?

Read 10,000 books, travel 10,000 miles.

What would you like carved on your tombstone?

I don’t want a tombstone. I’d like my children to scatter my ashes over a mountain or into the sea.

This interview has been edited and condensed.