Although America may not like doctors very much, it sure loves hourlong TV doctor shows. Starting in the 1960s with Dr. Kildare and Ben Casey and moving along through Marcus Welby, M.D., then St. Elsewhere up to House and Grey’s Anatomy, it seems there’s always a hit show featuring a handsome guy—with requisite quirk(s)—curing diseases, solving others’ nagging personal problems, and never quite getting the girl.

So when the new show Mob Doctor was announced, I admit I was excited. At last, maybe, a break from the usual. I imagined a grainy Edward G. Robinson type of thug working a fat, ashy cigar while sewing away on someone’s open heart, all the while hitting on a nurse and cutting a deal with one of the Five Families. Plus they snuck in a third element, a whiff of religion—at least in the ubiquitous Mob Doctor poster, which shows a willowy star whose surgical gloves, stained with old blood, are filled by hands met in prayer. Leaving aside the hygienic issues with the bloody-gloves-to-lips bit, I figured, here’s a show I’d watch—they look like they are finally going to have some fun crashing together the two tired, worn-out cliché-riddled TV workhorses: the genres of docs and wiseguys.

Oh well. Maybe next year. Sanctimonious doctor show (I want to make a difference) meet sanctimonious mob drama (you gotta get out of town for your own good). Yes there’s a switch or two. On the doctor side, we have not a brilliant, handsome, promising man with a GQ bod and a quirk or two, but a brilliant, beautiful, promising woman with a Maxim bod and a quirk or two. And on the mob side, rather than New Joisey guys tawkin’ like deh din’t ever go duh no friggin’ school, we got Chicahgo guys doin’ de same. Nice twist for sure.

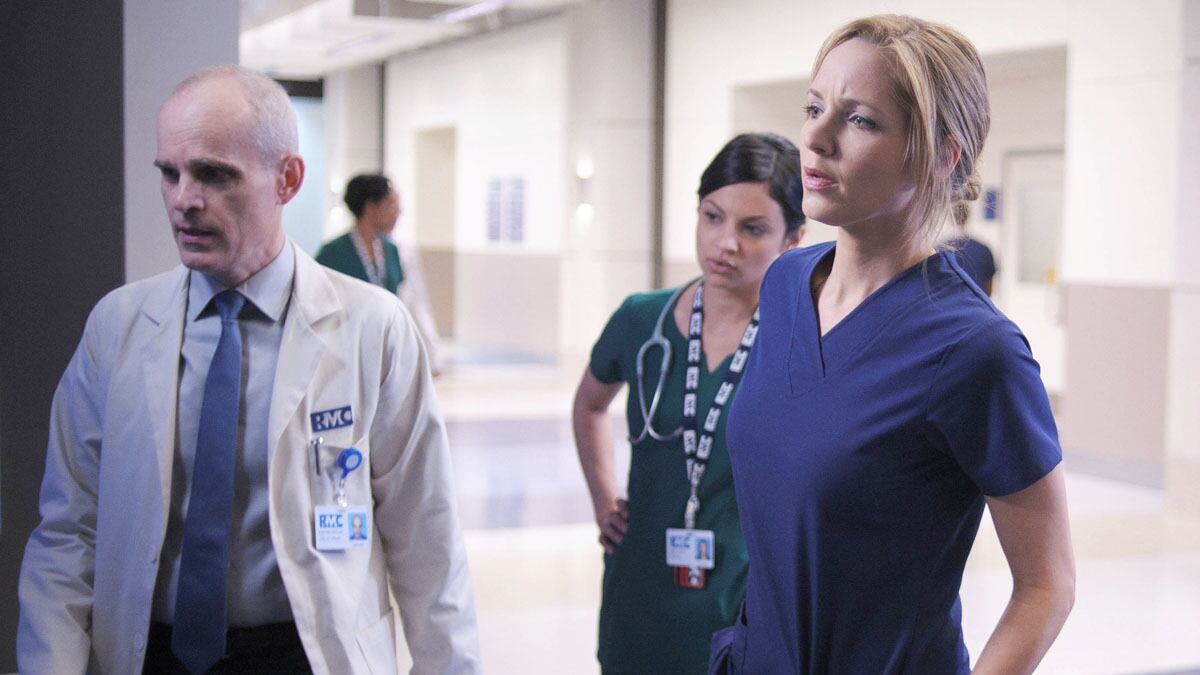

The problem is that, though stuffed full of plot and carried by the natural drama of any medical case (will he make it, Doc?) Mob Doctor is really boring. Yes there are plenty of twists and ethical quandaries and good-looking people walking, miffed, toward the camera without looking into it. But just when the medical part threatens to become interesting, they go to the Godfather nonsense; and when the mob business gets interesting—check that, it never gets interesting. So we are left with yet another promising concept that is much smaller than the sum of its parts. Ah, well.

Yet despite its probably limited lifespan, Mob Doctor does signal the start of the post-House generation of medical shows and an important shift in understanding the doctor-patient relationship. Doctors who watched House all had the same reaction—yes, Hugh Laurie, the male lead was (or was not) brilliant and caustic in the role—but why weren’t the doctors busier? There were four or five doctors working a week, maybe longer, on a single case. And the patient usually had a really large single room set in a glass cube with lots of windows for people to stare through.

In contrast an actual, um, doctor has a dozen patients in the hospital, is not surrounded by eager, lovable friends and protégés, has people waiting at the office, phone calls to return, dental appointments to keep—every day is a total mess, a landmine, just like any other job. Granted, we must assume that TV knows what TV should do—after all an actual day in a doctor’s life is not quite primetime stuff. For example, yesterday as I was talking to a patient I realized I had forgotten more or less what the patient’s problem was, exactly, then recovered my balance and muttered, “You, that knee, how is, your knee, it’s better, feeling better OK now?” Not the crisp dialogue one needs to fit into the tidy formula of crisis, ad, near-resolution, ad, funny side plot, ad, worse crisis, etc., the basic structure of the TV docto-drama.

But one patient a week? Is that the answer? Grace Devlin, our oxymoronic heroine of Mob Doctor, has a few more than that—OK one more—and they make a big deal of what long hours she’s working, but she seems to have oodles of time to visit her (hardscrabble, loopy) mom, her (frisky surgeon) boyfriend, and a sweet old mobster who loves her (not that way; this episode at least) as well as to drive around South Chicago in a Jeep Cherokee a lot. Worrying.

But that’s the point. The new House-ian shows are inaccurate not because of medical mistakes and mispronounced terms and unlikely diagnoses—though there are many—but because they so miss the core of the profession: the confusion, the doubt, the panic that you might have screwed up, the fog of regret and second-guessing that fills any doctor’s head. It makes sense from the doctor side—illness and disease are surrounded by curtness and temper and that weariness that seems like physical fatigue but isn’t. It isn’t at all pretty. But patients hate this—they want easy decisiveness and jolly confidence as we march calmly, peacefully over the horizon together. They want House. When I see a doctor, I too want House. Not because he is smart or does an American accent so well—but because he has so much time for me and only me. In a medical world aswirl with gizmos and supermeds and genetic testing, all an ill person really wants, it seems, is a minute of the doctor’s time.