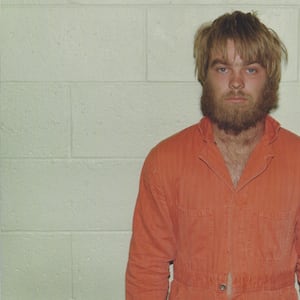

Prepare to be outraged yet again, because Making a Murderer returns to Netflix Friday (Oct. 19) with ten brand-new episodes that further detail the miscarriages of justices suffered by Manitowoc County, Wisconsin, residents Steven Avery and nephew Brendan Dassey, who were sentenced to life in prison in 2007 for the Oct. 31, 2005, slaying of Teresa Halbach.

As viewers of the first season know all too well, those guilty verdicts were a travesty, predicated on dubious evidence discovered by police officers that Avery was suing for $36 million (for having originally put him away for 18 years for a rape he didn’t commit), and on a Dassey confession that appeared to be coerced by law enforcement. When that initial run ended, both men were left languishing in prison cells. Thus, Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos’ superb follow-up predictably focuses on Avery and Dassey’s efforts to exonerate themselves—a quest that incites cautious optimism thanks to explosive new developments, as well as further indignation at the criminal justice system’s myriad failings.

Given that much of its material has been covered by the national media, Making a Murderer’s second installment isn’t really a true-crime mystery; rather, it’s an educational exposé about forensic scientific analysis and the inner workings of the American legal machine. What it reveals about the latter is dismaying: bureaucratic procedures and constraints that are outright unfair, to the point that hoping for an honorable outcome is borderline foolish, even when hope is the very thing needed to drive the process forward in the first place. In itemizing Avery and Dassey’s attempts to clear their name (by contending that duplicitous law enforcement officials and vile former district attorney Ken Krantz skewed facts, planted evidence, and employed unethical tactics to railroad them), the show illustrates the nightmarish nature of the entire judicial machine, where unreasonable burdens of proof and arbitrary time limits frustrate any chance to get to the truth.

Throughout these ten chapters, Avery and Dassey are more heard than seen—a symptom of their being locked away in correctional facilities. While recorded phone conversations and photos help keep their voices, and faces, as much as possible in the foreground, the centers of attention this time around are their legal teams. In Dassey’s corner are Center on Wrongful Convictions of Youth co-founders Laura Nirider and Steve Drizin. They aim to prove to a federal appeals court that their low-IQ client’s confession—the entire basis for his conviction—was a false one elicited by scheming police officers. Theirs is a mission fraught with obstacles, and via candid interviews and lucid graphics, the directors provide an up-close-and-personal view of these crusaders’ toil on Dassey’s behalf, which results in both improbable victories and dispiriting setbacks.

In Dassey’s segments, Ricciardi and Demos skillfully lay out the methods used to obtain (and identify) false confessions. Their no-frills systematic approach also buoys their depiction of Avery, whose new lawyer Kathleen Zellner—famed for exonerating 17 prior convicts—is the de facto star of Making a Murderer’s sophomore season. Promising that her thorough investigation will confirm either Avery’s innocence or guilt, Zellner comes across as a canny fighter whose flair for the spotlight (and gift for a well-timed sound bite to end an episode) is matched by her formidable intellectual acumen.

Before long, Zellner and a team of experts and aides are meticulously recreating every key piece of evidence against Avery, including blood spatter on Halbach’s RAV4 door, DNA found on her hood latch, and the fatal bullet found in Avery’s garage. Zellner’s strategy involves denouncing Avery’s prior counsel as well as examining, and debunking, the preposterous police narrative that led to his conviction—in particular, the idea that Halbach never left Avery’s homestead. Through masterful scrutiny of the slain woman’s cellular calls and day planner, and also the eyewitness testimony (and shocking computer hard drive material) of Dassey’s cousin Bobby, that notion is conclusively discredited. Along the way, Zellner not only becomes wholly convinced of Avery’s blamelessness (“I’d bet my life that Steven Avery is innocent,” she proclaims in episode two), but fashions a persuasive alternate theory as to how someone else might have murdered Halbach—and, moreover, the potential identity of the culprit(s).

The fact that Zellner only took on Avery’s case after Making a Murderer’s first season became a national phenomenon isn’t lost on Ricciardi and Demos, who from the outset shrewdly address their show’s own central role in this saga. On the one hand, it’s clear that the breakout Netflix hit has benefited its subjects in numerous ways (Zellner’s participation being only the most prominent example). And yet there’s also a nagging sense that such national notoriety has had its unavoidable drawbacks: an avalanche of armchair quarterbacking from TV pundits (which invariably bleeds into the duo’s legal endeavors); the appearance of various players who are mainly interested in exploiting Avery and Dassey’s plight for their own gain (notably, Avery’s short-lived fiancé Lynn Hartman); and the creation of a sensationalistic air, drummed up by Twitter posts and Dr. Phil appearances, that undercuts the gravity of the situation at hand, and any and all attempts to rectify it.

Ricciardi and Demos employ sober, straightforward aesthetics to scrupulously detail every aspect of their tale, never better than in late sequences in which Zellner explicates her theory about the actual fate that befell Halbach. Much like lawyers arguing in front of a jury, the directors present their findings with exhaustive precision, even as they craft a larger panorama of the case’s sprawling cultural connections and impact. It’s a portrait of prosecutorial misconduct and judicial inequity that doubles as a primer on the wonders of 21st century criminological technology—not to mention a damning censure (reminiscent of The Staircase) of the lengths to which the state will go to avoid admitting wrongdoing.

More moving still, however, is Making a Murderer’s concentration on the case’s enduring toll on everyone concerned, from Avery’s ailing mother and father (whose salvage business has been ruined), to Dassey’s misery-wracked parents, to the family and friends of Teresa Halbach, who naturally want closure on the tragedy and therefore detest the continuing attention received by Avery and Dassey, now painted as victims themselves. There’s no triumph and elation to be found here, only the infuriating and depressing impression that bad things can happen to innocent people, and that the truth is a slippery beast that, even when attained, doesn’t necessarily lead to justice. As Avery’s cousin Kim Ducat says, aptly summing up the ongoing affair, “The whole thing is sad.”