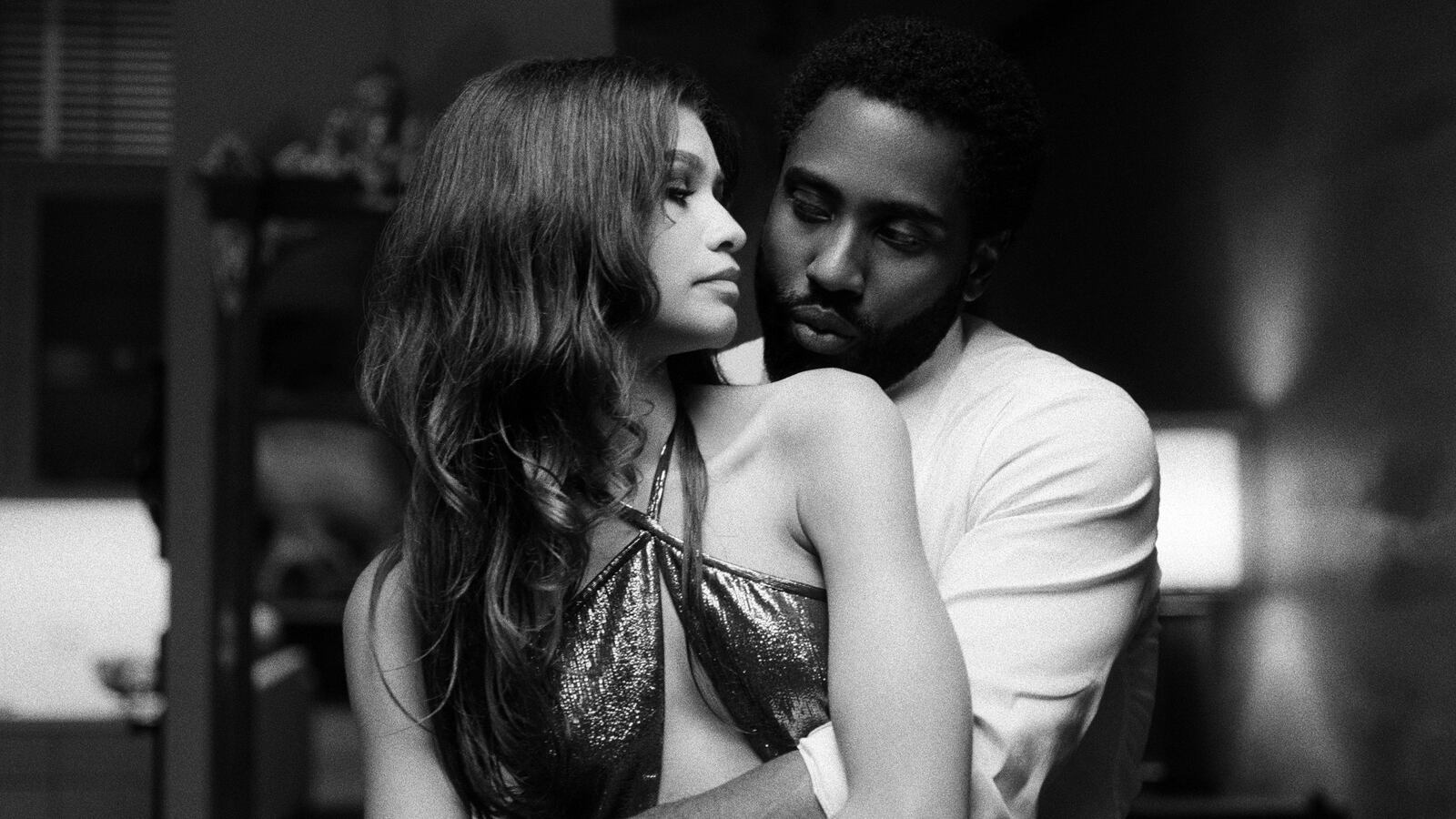

As much as Sam Levinson’s new film Malcolm & Marie, which arrives on Netflix today, has been advertised as an emotional two-hander à la Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage or John Cassavetes’ Minnie and Moskowitz, it’s actually a three-hander. The titular male protagonist played by John David Washington is up all night fighting with his model girlfriend (Zendaya) after he forgets to thank her at the premiere of his new film, for which she claims to be a primary muse. But there’s another character who emotionally unsettles him as much, if not more than the woman we see him battling it out with on screen: the white lady from the LA Times.

We initially hear about this woman, who could be a direct reference to actual LA Times film critic Katie Walsh (who panned Levinson’s 2018 film Assassination Nation) or a fictional representation of whitewashed media, in the first 10 minutes of the black-and-white chamber piece set in the couple’s stylish, Usonian home. Malcolm is doing victory laps around the living room after a warm, in-person reception to his movie. But he quickly begins to dread how his art will be received by critics, particularly white journalists who he anticipates will group him with other Black filmmakers like Spike Lee and Barry Jenkins and solely “make it about race.” He tells Marie, who’s outside smoking a cigarette, that he simply made a story about a drug-addicted Black girl trying to get clean, not an “acute study of the horrors of systemic racism in the health-care system.”

At this particular moment, it’s hard not to picture Levinson, the film’s writer and director, eagerly typing out what seems to be a long-awaited retort to criticisms of his Emmy-winning HBO show Euphoria, also starring Zendaya, about a teenage drug addict who happens to be Black but isn’t necessarily handled that way by the white auteur. It’s a recurring distraction in a film that fails to develop distinct voices for each of its characters in favor of laborious diatribes that serve Levinson at the expense of his creations. By the time the white lady from the LA Times is referred to as “Karen” in the third act, you feel sorry for the talented Black performers involved in what could’ve been a well-crafted homage to the relationship-in-crisis genre but reads more like a calculated exercise for its angsty white screenwriter.

Malcolm & Marie’s inescapable commentary on film criticism is hardly the only defect in Levinson’s extravagant quarantine project, but it’s the first domino in a never-ending series of misfires. For example, Malcolm’s opening monologue about the white gaze on Black film employs generic talking points made by Black creators over the years—some are legitimate, others are clearly lacking in nuance—and makes false generalizations about the landscape of journalism and modern film discourse. By Levinson’s estimation—and, therefore, Malcolm’s—Black critics like myself don’t exist nor do they have any influence on the way movies are received and debated in the zeitgeist. There are only “white-ass writer[s]” with fancy college degrees flexing their “woke” knowledge on race, gender, and socioeconomics. Marie chimes in occasionally to point out Malcolm’s hypocrisy (he hates the politicization of art but is working on an Angela Davis biopic) and pokes fun at his fragile ego throughout the film. But none of this makes the experience of listening to Malcolm’s repeated, long-winded tantrums more bearable for the audience.

Unfortunately, the portions of Malcolm & Marie about its lovers’ quarrel are just as unwatchable as Malcolm lamenting the dissection of art. Once again, these scenes feel more like opportunities for Levinson to flex his ability to construct flowery sentences than thoughtful storytelling. The film’s setup—that Marie is upset with Malcolm for failing to acknowledge her at his premiere—unfolds rather quickly and forces the characters to move on to a list of other grievances that don’t necessarily build on one another and make the film feel unfocused. For instance, we aren’t allowed to sit with Marie’s accusation that Malcolm is indifferent to her before she starts oppositely claiming he doesn’t want her to have her own life. It feels more like Levinson is moving down a list of typical arguments an egocentric artist might have with his long-suffering girlfriend as opposed to developing an actual plot. Most notably, the monologues themselves are overwritten and lack the looseness of a real conversation between two partners. Despite the fluctuating emotions on display, which is a page directly out of Cassavetes’ book, nothing feels authentic or spontaneous. We never experience any real sense of uncertainty or danger as these two impassioned characters go at it, even in the moments when one of them is wielding a knife.

As the film goes on, you realize there’s more to be gleaned from the couple’s apparent age difference and the circumstances under which they met than from any of the film’s overwrought dialogue. We find out that Malcolm met Marie when she was a drug addict and helped her get clean, but the film doesn’t illustrate if and how his role as her caretaker and her indebtedness to him has affected the terms of their relationship. A sharper film would highlight how Marie’s combined youth and maturity stand in opposition to Malcolm’s man-child state. But this dynamic is underplayed in favor of an uninspired message about gratitude and humility.

If Malcolm & Marie accomplishes anything it’s a showcase for Washington, who’s uncharacteristically loose and occasionally charismatic despite the exasperating material he’s given. You appreciate his big swings for what they are, even when his capital-A Acting leaves him with nowhere to go, which mostly falls on the directing. Zendaya’s Marie adds some much-needed mystery and ambiguity to an overly straightforward film and is able to overcome cinematographer Marcell Rév’s leering gaze. Whether it’s her eerily-calm disposition when she’s holding a cigarette or the way her eyes glaze over as she’s dutifully preparing dinner for her man, you feel like you’re about to be introduced to one of Gena Rowlands’ signature perplexing madwomen. But this archetype only flourishes in the right hands.

Maybe if Levinson didn’t waste substantial parts of his script trying to get ahead of criticism, Malcolm & Marie would manage to be a fun, sizzling piece of entertainment. But the “visionary filmmaker” (as he’s credited in the film’s trailer) inadvertently sets viewers up to evaluate his work’s own flaws. Above all, there’s something morally suspect about Levinson, a white creator whose successful career has largely been afforded to him by his Oscar-winning father Barry Levinson, using a Black artist’s experiences as a smokescreen for his own gripes. But this film would argue that race isn’t always a factor.