After the third sexual assault of an elderly woman in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1985, police were desperate for an arrest. So they beat a 17-year-old boy, framed him for the crime, and sent him to prison for life until his case was overturned in 2016, he alleges in a new lawsuit.

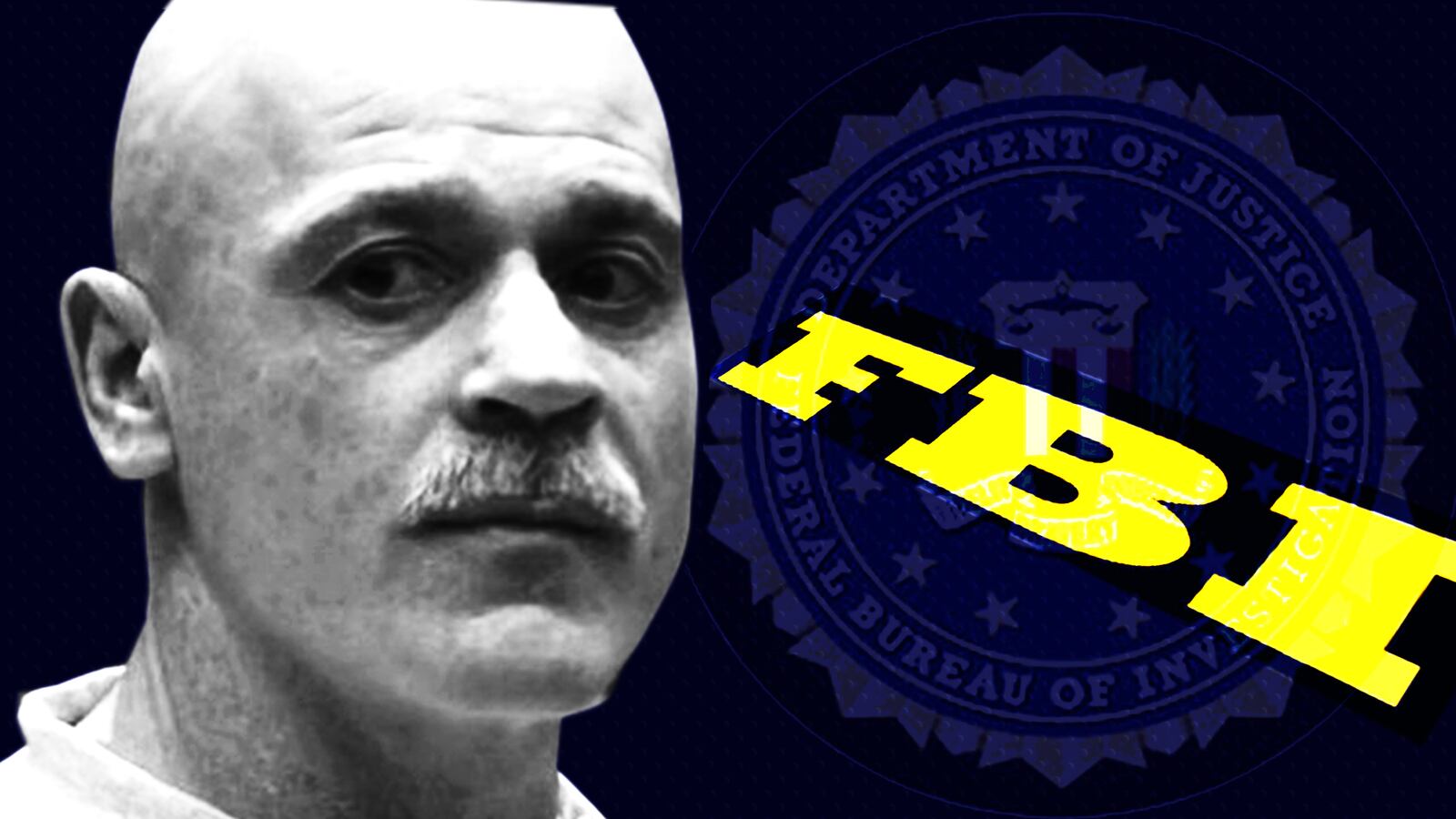

George Perrot spent 30 years in prison for a rape he did not commit. His now-overturned conviction was based on a confession he says was forged in his name, and evidence testing the FBI now acknowledges as dubious, Perrot claims in his lawsuit against the city of Springfield and members of the FBI.

In 1985, Perrot was 17 and no friend to the Springfield police. He admits in his lawsuit to drug use and purse-snatching as a teenager, and accuses Springfield officials of harassing him in turn. But when elderly Springfield women began reporting sexual assaults by what appeared to be a serial rapist, Perrot found himself implicated in a much larger crime than petty theft.

A 78-year-old woman identified as “M.P.” was the third victim of the apparent crime wave. Around 4 a.m. on the morning of Nov. 30, 1985, a man broke into M.P.’s home and raped her on the floor, she testified. Perrot wasn’t even in Massachusetts at the time of the attack, he claims. He was in Vermont with friends until later that day.

A week passed with no arrests. Police were desperate to name a suspect in the increasingly high-profile crime spree, Perrot’s suit alleges. Soon, apparently without evidence, the suspicion would fall on Perrot.

Perrot got high with his friends the night before his arrest, drinking heavily and popping eight Valium pills, he claims. He also admits to spending the early morning engaged in petty crime. He broke into a house, but left when he realized the owners were home. He stole a purse in a Denny’s parking lot, stumbled home, and passed out.

Two hours later, his sister shook him awake. Police were there to arrest him for the break-in and purse theft. Confused and still intoxicated—he mistook his sister for his girlfriend—he went with police. But the arrest quickly became violent, he alleges.

“During his arrest and on the way to the Springfield police station, [police] viciously beat [Perrot],” his suit alleges. “They kicked and hit [Perrot], and then threw him over a small fence. On the way to the police station, [police] threatened to kill him.”

He claims the beatdown continued in the station, where officers allegedly interrogated the disoriented teenager without a lawyer for 12 hours. They repeatedly turned away his mother. Police “purposefully did not let [Perrot] sleep,” his suit alleges. “Instead, any time he tried to get some rest, one of the Defendants would come and bang on the cell doors to ensure he was awake.”

Perrot claims investigators fed him details about M.P.’s rape, in a bid to make him confess to the crime. Even “highly intoxicated… often incoherent, and even at times suicidal,” Perrot insisted he’d had nothing to do with the crime. Although Springfield police had audio and video recording equipment available, none of Perrot’s interrogation was filmed.

But sometime after the interrogation, investigators produced a “confession” that appeared to show Perrot admitting to breaking into M.P.’s home. The contents of the confession and Perrot’s signature on the form are both fabricated, he contends in his lawsuit.

With their supposed confession in hand, investigators attempted to have M.P. identify Perrot in a police lineup. But even that process was rigged, he alleges. M.P. described her attacker as a clean-shaven, short-haired man between 20 and 30 years old. Perrot, only 17, had “long, wild hair,” a mustache and a goatee, according to his lawsuit.

Instead of assembling a lineup of men who looked like M.P.’s description of the attacker, police assembled a lineup of men who looked like Perrot, some of whom were obviously police officers, Perrot claims in his suit. Even so, M.P. would not identify Perrot as the guilty party.

Without M.P.’s testimony, prosecutors attempted to introduce new evidence against Perrot. They claimed to have found a single hair at the crime scene, and bloodstains on M.P.’s bed. Those samples caught the attention of Francis Bloom, an assistant district attorney was particularly critical of Perrot, the lawsuit alleges. In his diary, Bloom allegedly described the teenage Perrot as “inherently evil” and a “sociopath,” and even drove to Washington, D.C., to personally deliver evidence to the FBI for testing.

The FBI analyzed the hair sample with a technique called hair microscopy, during which investigators compare two hair samples under a microscope for physical similarities. The technique, which does not analyze DNA, has since fallen out of favor with investigators. Three hundred and fifty-one convictions have been overturned using new DNA testing technology. Twenty percent of those false convictions were made using microscopic hair testing, the Innocence Project reported in 2017.

FBI agents knew the method was “junk science” even in 1985, Perrot’s suit claims. Even if the technique was scientifically sound, the hair found in M.P.’s home and Perrot’s hair “did not match in any substantial way,” according to the suit. But instead of revealing the differences between the two samples, an FBI agent testified at Perrot’s trial that the two hairs were consistent.

The FBI also found the bloodstains on M.P.’s bed to be too old to have resulted from the rape, which took place on her floor. The stains were so old, researchers could draw few conclusions from them, other than that the blood belonged to a male. In trial, prosecutors argued claimed the blood was “consistent” with Perrot’s.

He was convicted to life in prison.

But new evidence-testing models and lingering doubts kept Perrot’s case alive. In 1990, while trying to secure a new trial, Perrot’s lawyers discovered that Bloom, the assistant DA had forged Perrot’s signature and that of a Springfield police detective. A judge publicly censured Bloom, calling the forgery “outrageous” and “reprehensible,” the Boston Globe reported.

The judge still upheld the conviction. Perrot’s guilt hung on the single strand of hair discovered in M.P.’s home.

But as another decade passed, with Perrot still behind bars, the FBI launched an investigation into the hair microscopy technique used to tie him to the crime scene. In 2015, the FBI conceded that the technique was flawed. The agency said it would notify people whom it believed may have been convicted on shoddy hair analysis. Perrot was one of the defendants to get the call.

With his confession revealed to be a forgery, and his hair analysis revealed to be junk science, Perrot’s conviction quickly fell apart. In 2016, a judge ordered a new trial for him, and in 2017, a judge tossed the charges altogether. Perrot was a free man.

“Without that [hair analysis], the Commonwealth’s claims of Perrot’s violence were open to several lines of attack conducive to the creation of reasonable doubt,” the judge wrote in the decision to toss the case. “It is not a close call.”