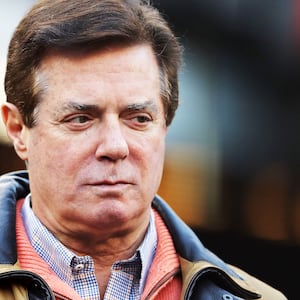

Paul Manafort’s 47-month prison sentence makes the stark disparities that exist in our criminal-justice system painfully clear, but the former Trump campaign chairman shouldn’t rest easy just yet: It’s unlikely to derail Special Counsel Robert Mueller.

And for anyone reading between the lines in the Russia investigation, Mueller’s still got plenty to work with.

In what surely felt like a slap in the face for many watching the Russia probe, U.S. District Judge T.S. Ellis imposed the sentence of just under four years on Manafort even though the court’s own probation department had calculated the sentencing guidelines at 19 to 24 years. And he did this despite the fact that Manafort expressed no remorse.

Judge Ellis explained that he thought the guidelines range was “quite high.” The guidelines range was high only because Manafort’s conduct was egregious. Sentencing guidelines are based on a number of factors, such as the amount of fraud involved in the crime, whether the defendant used sophisticated means to commit his crime, whether the defendant was a leader or organizer of criminal activity, and whether he has accepted responsibility for his wrongdoing. In Manafort’s case, the aggravating factors piled up, yielding the 19- to 24-year range.

The guidelines are based on data that the U.S. Sentencing Commission collects from cases across the country to find a range that represents “the heartland” of sentences for similar crimes. Judges are required to consider the guidelines as a starting point, and look to other factors as well, such as the nature of the offense and the characteristics of the offender, in fashioning a fair sentence for the defendant. The idea behind the guidelines is that sentences for similar crimes should be similar, regardless of the particular judge who is imposing the sentence, to avoid unwarranted disparities among defendants. If a judge varies either upward or downward from the range, he is supposed to articulate the basis for the variance.

In the case of Manafort, I believe that the drastic variance from the guidelines range has little to do with Manafort’s connections to Trump, though Judge Ellis openly expressed hostility to the special counsel and its prosecution of Manafort throughout the case. Instead, I think it reflects the class and racial disparities that exist in the criminal-justice system. As a former federal prosecutor, I have often seen white-collar defendants receive sentences below the calculated guidelines range. This practice sends a terrible message that wealthy and powerful defendants are treated differently than other defendants. I didn’t see many drastic drops from the guidelines in sentences for indigent defendants.

During his sentencing hearing, the closest Manafort came to contrition was saying that he felt shame and suggesting he had already been punished. This is a common trope from white-collar crime defendants, who suggest that they don’t need to go to prison because their loss of income and status in the community is punishment enough. They submit letters of support that their expensive lawyers have billed many hours gathering from prominent people to praise their good works.

Indigent defendants, on the other hand, don’t receive leniency because they have suffered harm to their status in their community. Their overworked court-appointed lawyers don’t have the resources to collect letters, nor do the defendants know the kinds of prominent people who might persuade a judge to impose a lower sentence. We fill our prisons for lengthy periods of incarceration with disadvantaged people with few economic opportunities, but defendants whose crimes are motivated by nothing more than greed are the ones who get a break. The sentence imposed by Judge Ellis appears to reflect that tendency.

What, then, does Manafort’s sentence mean to the Mueller investigation?

First, Manafort cannot rest easy just yet. Next week, he will face sentencing from Judge Amy Berman Jackson in the District of Columbia, where Manafort pleaded guilty to two conspiracy counts encompassing violation of the Foreign Agent Registration Act, money laundering, tax fraud, and obstruction of justice.

Judge Jackson is very familiar with some of the aggravating facts in Manafort’s case. In recent weeks, the parties litigated whether the government acted in good faith in determining that Manafort had breached his cooperation agreement by lying to the government, and Judge Jackson ruled against Manafort. Judge Jackson also revoked Manafort’s bond and put him in jail when he was charged with witness-tampering.

The statutory maximum sentence in the District of Columbia case against Manafort is 10 years, which cannot be exceeded, even though the guidelines range is higher. Judge Jackson also has the ability to impose her sentence concurrently or consecutively to Judge Ellis’ sentence. The maximum sentence she could give, then, would be 10 years consecutive to the 47-month sentence imposed by Judge Ellis, for a total of just under 14 years. A lengthy sentence would deter others from committing the types of crimes that Manafort committed, and would also encourage defendants to cooperate with the government fully and completely.

Second, is Manafort angling for a pardon? His failure to express remorse at his sentencing hearing may have been some effort to maintain his innocence. Innocence, however, is not necessary for a pardon. In fact, individuals seeking pardons are usually required to express remorse and accept responsibility for their crimes before being granted a pardon. The more certain sign that Manafort may be seeking a pardon is instead his failed effort to cooperate with the government. Manafort gave up the benefit of a recommendation for a lenient sentence when he lied to prosecutors about a number of matters, including his communications with Konstantin Kilimnik, who Mueller says has ties to Russian intelligence. What about that topic does Manafort so desperately want to conceal that he would risk a longer prison sentence rather than disclose it? Was Manafort’s failure to fully cooperate an effort to curry favor with Trump in hopes of a pardon down the road?

And finally, Mueller may still find evidence of a conspiracy between Russia and Manafort or other Trump campaign officials to attack the 2016 presidential election. After the sentencing, Manafort’s lawyer said that the case exposed no evidence of “collusion with any government official from Russia.” The specificity of that statement begs several questions—was there collusion with Russians who were not government officials? Was there collusion with government officials from other countries? Is “collusion” the word of choice because collusion in this context is not a crime? The fact that Manafort’s case is over does not mean that Mueller is done investigating all of his activities or the activities of others relating to Russia. In fact, the redactions from Mueller’s recent court filings in the Manafort case, as well as redactions in filings in the case against former Trump attorney Michael Cohen, indicate that Mueller’s investigation regarding Russia is ongoing.

Manafort’s cooperation and even his sentencing did not go as Mueller likely had hoped, but Manafort’s willingness to forgo Mueller’s recommendation for a reduction in sentence suggests there is more that he’s hiding. And if it can be found, there should be no doubt that Mueller will find it.