If Manhattan prosecutors don’t indict former President Donald Trump with the grand jury they’ve got in the next nine days, the key witness investigators have used to build their entire case says he won’t help revive it in the future.

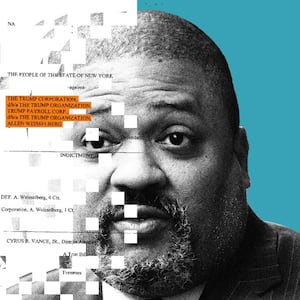

Michael Cohen, the New York lawyer Trump used for years as his family company’s trusted consigliere, told The Daily Beast he’s already wasted too much of his time on a case that slowly and then suddenly doesn’t seem to be going anywhere. Prosecutors only have until the current grand jury’s term expires on April 30 to issue charges, at which point they must ask jurors who’ve already done this for six months to continue hearing evidence—or call the whole thing off and awkwardly make the entire presentation all over again in front of another 23 jurors.

If this grand jury is let go, Cohen won’t play ball. Asked if he’d be willing to sit down again with investigators or testify at a future trial against Trump, Cohen responded with utter exasperation.

ADVERTISEMENT

“No. I spent countless hours, over 15 sessions—including three while incarcerated. I provided thousands of documents, which coupled with my testimony, would have been a valid basis for an indictment and charge,” he said.

“The fact that they have not done so despite all of this… I’m not interested in any further investment of my time,” he said.

Cohen was a cornerstone of the investigation from the moment it was launched by the previous district attorney. Case in point: The entire probe is named after him. Court records made public weeks ago show that Manhattan prosecutors referred to the investigation internally as “The Fixer,” a reference to Cohen’s role as Trump’s mob-like consigliere.

Trump had relied on Cohen as his lawyer to protect his 2016 presidential campaign by delivering hush money payments to two women with whom he’d had sexual affairs: former Playboy playmate-of-the-year Karen McDougal, and porn star Stephanie Clifford, better known as Stormy Daniels.

When former DA Cy Vance Jr. realized federal prosecutors in New York weren’t going to pursue a case against Trump for election violations and fraud while he was in the White House, he launched his own local probe. Vance convened a grand jury that sent a subpoena to the Trump Organization on Aug. 1, 2019 demanding records about the hush money payments, according to court records.

Later that same month, several Manhattan prosecutors took the two-hour drive north of the city to the federal prison at Otisville, New York, where they met with Cohen—one of the very first interviews in the case.

Prosecutors ultimately visited him three times behind bars, and nearly a dozen times after his release, taking extensive notes in which he explained how the Trump Organization operated like a mafia—how Trump avoided putting anything damning in writing, instead using innuendo to order his lieutenants to engage in fraudulent behavior.

His documents and insider perspective helped prosecutors build their case against the Trump Organization and its former chief financial officer, Allen Weisselberg, who were both indicted last summer for criminal tax fraud. Cohen has been so helpful, in fact, that Weisselberg’s lawyers are trying to get the case dismissed by painting the entire prosecution as a revenge plot by his former colleague.

Documents that the Manhattan DA’s office has shared with Weisselberg’s legal team—but that remain sealed from public view—allegedly show how “prosecutors up and down the ranks, including DA Vance himself, thanked Mr. Cohen for his cooperation,” defense attorney Mary Mulligan wrote in court papers filed in February.

Defense lawyers for the Weisselberg and the Trump family company, who have exclusive access to the DA’s investigative materials in the run-up to their upcoming trial scheduled for this summer, claim in court papers that prosecutors have been “spending far more time with Cohen than with any other witness.”

Cohen gave investigators leads, guided their subpoenas, helped them craft questions for witnesses they put before the grand jury, and even suggested that prosecutors target Weisselberg as the “weak link” who could flip on Trump, according to court documents filed by Weisselberg’s legal team.

But judging by all the available public evidence, Weisselberg hasn’t turned on his boss. Instead of cutting a deal with prosecutors, he’s aggressively trying to get the indictment dismissed. His right-hand accountant, company controller Jeffrey S. McConney, had the power to bolster the case against the Trump Organization but actually made himself the fall guy.

Meanwhile, the second phase of the investigations appears to be falling apart. The grand jury put together to presumably indict Trump hasn’t been asked to yet, because Vance’s replacement, DA Alvin Bragg Jr., has refused to sign off on it. His reticence pushed the investigation’s top two prosecutors to quit in protest in February. A third top prosecutor has become less involved in the case. Prosecutors began to return evidence to witnesses. A person familiar with the situation described the team as “gutted” and a “shell” of its former self.

For some, there’s a small glimmer of hope that New York’s unique law freezing the statute of limitations on old crimes might allow prosecutors to revive this effort in the future by waiting for Bragg to change his mind or wait for his replacement if he is not re-elected in 2025. But that would require spinning up another grand jury, bringing back several witnesses, and making the same presentation all over again.

And that carries its own pitfalls, warns Alissa Marque Heydari, a former Manhattan assistant district attorney who now runs the Institute for Innovation in Prosecution at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

“You don’t want to start from the top,” she said.

Major cases tend to have a large number of witnesses and getting them all to interrupt their jobs and parenting is a heavy burden, she explained. Plus, defense attorneys will eventually get copies of their grand jury testimony—both versions—and zero in on any variations in their memory.

“Generally speaking, re-presenting a case is logistically difficult and also long-term problematic for the case. You’re creating more opportunity for impeachment of a witness,” Heydari said. “You now have a witness who has testified twice. Nobody is going to testify the same way every single time. The defense can say this person is clearly lying because they can’t keep their story straight.”