So the cultural melt continues, and sometimes in an unexpected manner. Damien Hirst, a hands-off Conceptualist, becomes a born-again painter. Now John Zinsser, the well-regarded New York abstract artist, has Art Dealer Archipelagoes, a curiously moving exhibit of Conceptual drawings, up at James Graham & Sons in New York.

Click Image Below to View Our Gallery of John Zinsser's Maps

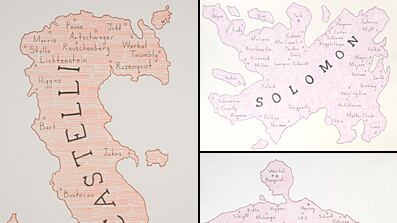

In this show, Zinsser represents various Manhattan contemporary-art galleries as islands. Each island is named for the dealer, not the gallery, and the artist inscribes the landscape with the last names of some of the gallery artists, as if they were towns, and giving away nothing in the lettering to indicate the size or permanence of reputation. Those on the embryo-shaped Castelli island, for instance, include Andy Warhol, Cy Twombly, James Rosenquist, Frank Stella, and Jasper Johns, as well as Lee Bontecou and Larry Poons, but also Nassos Daphnis and Salvatore Scarpetta, who were two of Leo Castelli’s first artists, and to whom he characteristically remained loyal until the end.

Sperone, Westwater and Fischer get three adjacent islands on the same piece. The De Land island is named for the late Colin de Land of the defunct gallery American Fine Arts, and is dotted with such settlements as Mori, Fend, Pfahler, Dogg, and Wachtel. Mariko Mori has, of course, had a robust career whereas “John Dogg,” was widely believed to be a fictional construct whose work was actually made by de Land and Richard Prince. Kembra Pfahler, the lead of the cult porno-rock band, The Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black, has since been an attraction at Deitch Projects. Peter Fend is an ur-environmental artist and Julie Wachtel, whose savagely cartoony work would have been a snug fit in Pop Life at the Tate Modern, now works at Condé Nast.

“It wasn’t conceived as a Conceptual project,” Zinsser says of his inspiration. “It came about very organically. I have a studio space over in Greenpoint [Brooklyn]. But over this summer I started drawing at home a lot.”

One source was a 1950s Rand McNally atlas he picked up on a stoop on Clinton Street. “I started to play around, not thinking it was going anywhere, just with these map shapes. One idea was how to marry words and image.” The first dealer island originated in another book, a 50-year history of the Tibor de Nagy gallery. “I started to use these names. Jane Freilicher and Neil Welliver and so forth as place names. And I realized how beautifully this idea of the surname transferred into a sense of place, “ he says.

As the idea took on momentum, Zinsser channeled his own history. “A lot of the galleries that I chose were very big when I was first out of college,” he says. “To me everything was so significant. I just thought that any artist who showed in a gallery was famous. And I wondered how they got there.”

To a young artist in the 1980s, the SoHo galleries that mattered seemed an unreachable territory, a no-go land. “All of this territory was already taken. SoHo was an ivory tower. These galleries like Paula Cooper seemed impenetrable to the outer world,” Zinsser says. “Then in the 1980s, one thing that the East Village taught me was that anything was possible, that anybody could be an artist. It was a tremendously exciting democratizing time.”

Zinsser’s topographies can be read as a record of these changes, and of others. The placement of names is significant. “When I did the Richard Bellamy one, I put Myron Stout on a little island of his own because he was kind of a solitary artist,” Zinsser says. “In the Sonnabend one, Jeff Koons is off on an island. In the Shafrazi island, Warhol and Basquiat are up on this little isthmus together, a little spit of land.

“It’s really a show about how these New York dealers made art history. Much more than the institutions, much more than the critics. It’s the dealers that mapped out post-war American art history,” he continues.

“This show is all about shared history. It’s like a catalyst for viewers. We’ve spent 25 years going to galleries and knowing artists. The gallery world that I depict is kind of a self-contained universe unto itself. So that at an opening when people see anyone’s name, not necessarily the dealer names, but the artist’s names, it opens up the floodgates of anecdotal material, where people immediately start telling stories about a particular artist. What happened to so-and-so and so-and-so.”

As with most work scrutiny of fairly recent history, there is a bittersweet element to the work, a necessary element of melancholy. The majority of Zinsser’s islands are gone now. There are survivors, such as Sonnabend, Sperone Westwater and Shafrazi Gallery, but Shafrazi nowadays shows Bacon and Picasso. And many, many, many of the artists are gone, too. “To me each of those names is so significant,” Zinsser says wistfully. “And all these artists. Where are they now?”

Zinsser is now taking the project further, and fine-tuning it.

“I want to be specific to the years 1986 to 1987. It would include Mary Boone at the moment when she was showing the German Neo-Expressionists. And also American abstract painters like Gary Stephan and Ross Bleckner. And Jean-Michel Basquiat. It was really such an interesting conflation of these different trajectories into that singular gallery at that time. And the East Village was also something I was very involved with.”

So, as to the cultural melt, Zinsser has found the making of his Archipelagoes liberating but not that dramatic a change.

“It’s funny. Once I freed myself from the tyranny of being identified solely as an abstract painter, I began to think of all these projects that had to do with history and the representation of history,” he says. “But for me there is always subject matter in abstract painting. It’s just that people do not make the overt connection. I’m dealing with the same subject matter in this show that I’ve always dealt with.”

Plus: Check out Art Beast for galleries, interviews with artists, and photos from the hottest parties.

Anthony Haden-Guest is the news editor of Charles Saatchi’s online magazine.