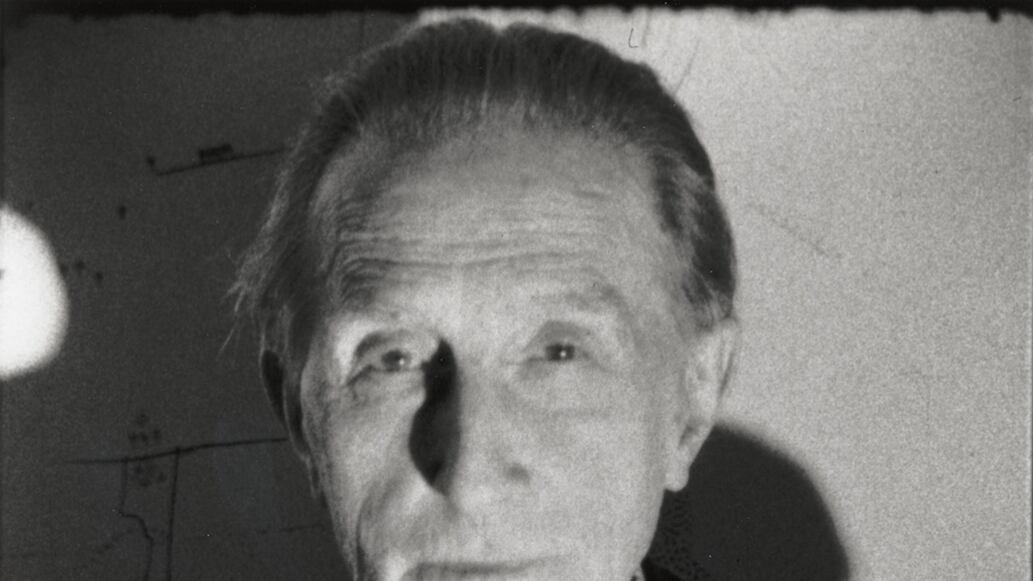

This is Marcel Duchamp, at age 78, in a single frame from one of Warhol’s “Screen Tests”, the four-minute filmed portraits that Warhol made by the hundreds in the mid 1960s, mostly by pointing his movie camera at a subject and asking them not to move. Twenty wonderful “Tests”, on loan from the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, are being shown at the museum of the Rhode Island School of Design, in projection, as they originally were, and unlooped, as they ought to be seen. (You need the suspense of knowing that if you blink, you may miss a detail that you won’t catch again).

The “Screen Tests” are now acclaimed as masterpieces of world portraiture, like Rembrandt with motion added, but that tends to tame them. Like almost all of Warhol’s mature work, when the “Tests” first appeared they seemed absurd and conceptual and divorced from the entire history of normal, expressive art making – they seemed Duchampian, that is, rather than Rembrandtian. At first, Warhol’s Pop art was also termed neo-Dada, which makes sense, given that Warhol admired and collected the works of Duchamp and Duchamp was an ardent Warhol fan. He saw Andy as his comrade in anti-retinal and utterly abnormal art. (“If you take a Campbell’s Soup can and repeat it fifty times, you are not interested in the retinal image. What interests you is the concept …” Duchamp once said.) But, as usual with Warhol, that take on him needs to be instantly contradicted: Seeing 20 of the “Screen Tests” in a row makes you realize just how carefully crafted they really were, as visual experiences. The lighting is immaculate and sometimes unusual, while also quite varied from subject to subject. The camera height and position also seems very considered, with each “Test” shot from higher or lower depending on how much elegance and elongation Warhol wanted to add to his sitter. (Lowering the camera is an old fashion photographer’s trick – which Warhol chose not to use with Duchamp, whose eyes line up with the lens.) Yet all that style leads to an unanswerable question: How much is it Warhol’s doing at all, and how much is it the product of a few tech-savvy followers, such as lighting designer Billy Name, making choices Warhol could care less about?

One final, funny thing, typical of the wylie Warhol: Alone among “Screen Test” sitters (as far as I can tell) Duchamp, Mr. Anti-retinal, is filmed against the backdrop of a perfectly optical work of art. It was a large-scale drawing by his new friend and acolyte Gianfanco Baruchello, and was on view at the chess-foundation benefit where Warhol and his camera caught up with Duchamp. That is, Duchamp is shown as being all eyes for a work of visual art – or is Warhol rather showing Duchamp making eyes at Warhol himself, who stares back through his own mechanical eye?