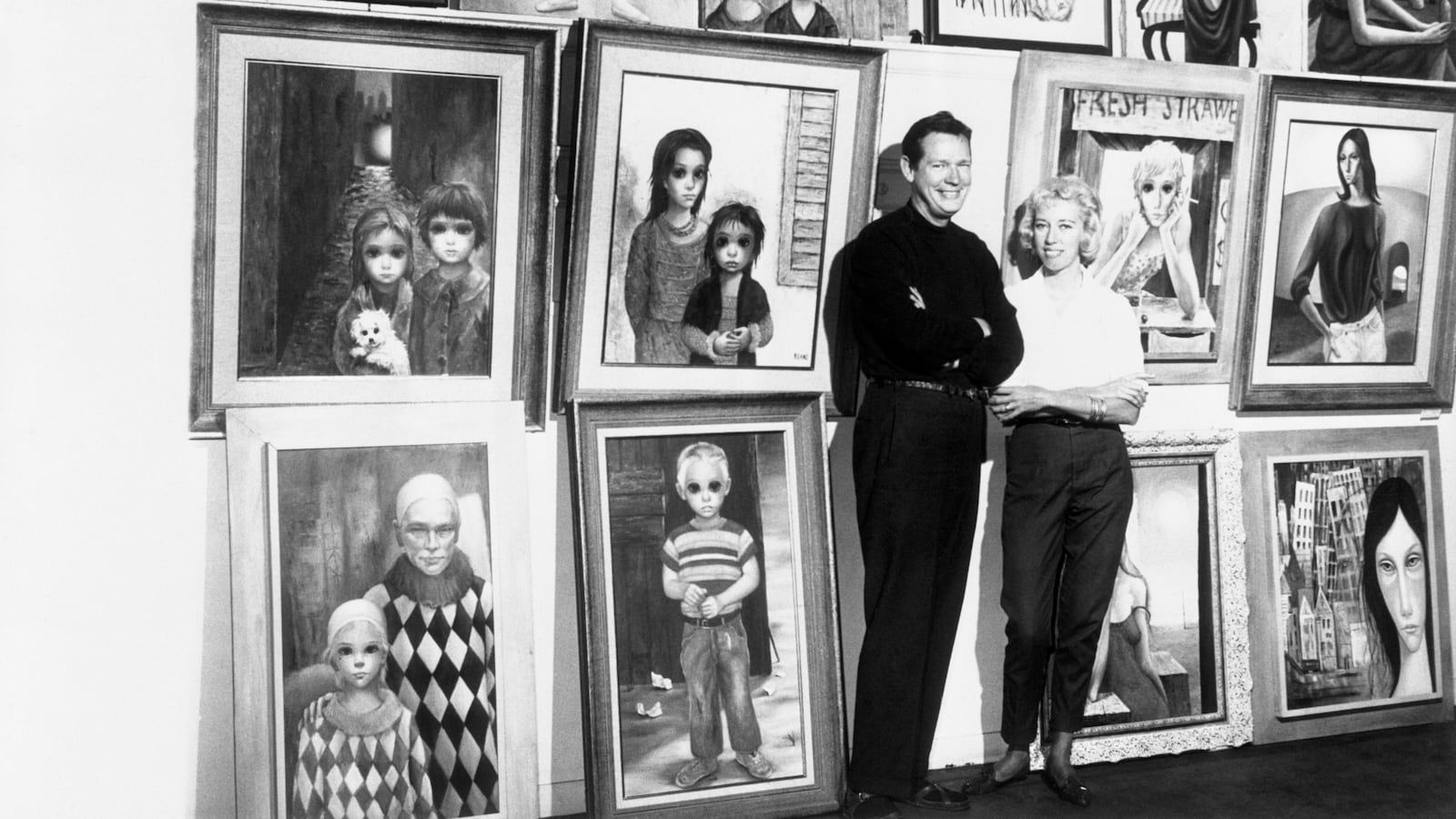

Margaret Keane, the rightful artist of the critically panned but publicly adored paintings of saucer-eyed, anemic waifs, died Sunday at her home in Napa, California. She was 94. Keane’s big-eye paintings were a source of such fierce controversy that they even inspired the 2014 Tim Burton film Big Eyes, a biopic that once and for all told the true story of the artist behind the ridiculously popular kitschy paintings.

In 1955, Margaret Keane’s husband, Walter Stanley Keane, began selling her paintings as his own work. Not even Margaret was aware of the deception at first. She only discovered the con one night at the Hungry i, a comedy club in San Francisco where, banished to the corner, she observed Walter representing her work to buyers. Only when a customer came up to her and asked if she also painted did she realize that her husband was taking credit for work she had created.

Walter’s reasons made some sense to her: He explained that buyers are receptive to artists representing their personal work and that paintings by male artists tend to sell better. She was also afraid of her husband, who claimed he was mob connected. So, she remained complicit, anonymously churning out the portraits of children with enormous eyes while Walter lived a luxurious playboy life with orgies in their kidney-shaped pool, all of it financed by the sale of Margaret’s painting.

Most art critics loathed the overwrought sentimentality they saw in the Keane paintings, but Walter defended “his” art, claiming the subjects in the paintings were inspired by children he had observed in the wake of World War II, children in such despair that they “couldn’t even pray.” And not everyone in the art world hated the pictures. “I think what Keane has done is just terrific,” Andy Warhol said in a 1965 Life magazine profile. “It has to be good. If it were bad, so many people wouldn’t like it.” Lawrence Alloway, curator at New York City’s Guggenheim Museum, echoed Warhol’s enthusiasm: “What I really love about Keane is that he is so commercial.” Alloway went on to celebrate the work as “incredibly vulgar,” “weird,” and in “heroic bad taste.”

From the first date to divorce, the couple were together 11 eventful years, during which they not only perpetrated one of the greatest art frauds of the 20th century but were themselves the victims of a heist.

Once, at a Keane showing in the palatial Shamrock Hotel in Houston, Texas, a viewer spotted a painting he wanted to give his wife for her birthday. Because it was Sunday, the banks were closed, and the buyer said he was due to fly home to New Orleans that evening to celebrate with his wife. So Margaret, fooled by the man’s apparent sophistication, accepted a check for the piece and let him leave with the painting. The bounced check was returned the following day with a request to notify the FBI. The man had been on the bureau’s Ten Most Wanted list for passing rubber checks throughout the South and had eluded the authorities for two years. A few months later, the chief of police in Austin, Texas phoned the Keanes to report the painting had been recovered and the perpetrator caught. The chief’s daughter, who had followed the news stories about the con, had seen the painting hanging in an Austin penthouse apartment when she attended a party. The painting was later purchased by Joan Crawford (In an interview with Mike Wallace, Keane proudly said of that painting that Crawford is “standing in front of it on the cover of her new book.”)

After the couple separated in 1965, Margaret moved to Honolulu, where she met and married Dan McGuire. The popularity of the paintings waned. Attempting to dispel the notion that there was a behind-the-scenes assembly line creating all the big-eye paintings, she revealed in a 1970 San Francisco radio show that she had painted all of them without the help of Walter or anyone else. “I couldn’t even teach him to paint,” she said. “I did the paintings. Sometimes he painted a little of the backgrounds.” The revelation enlightened the public and enraged her ex husband. Bill Flynn, a reporter at the San Francisco Examiner, organized a paint-off in Union Square to determine who had created the masterpieces. “Someone in the audience played ‘High Noon,’” Margaret later recalled. “And, of course, Walter didn’t show up,”

In 1986, Margaret sued both her ex-husband and USA Today for maintaining that Walter Keane was behind the big-eye paintings. A judge challenged the pair to paint the eyes. Walter said he could not paint due to a shoulder injury. Margaret was awarded $4 million in damages but never collected. The verdict was upheld on appeal, and Margaret Keane got credit for the paintings.

Artist Margaret Keane (L) and actress Amy Adams attend the "Big Eyes" New York premiere at the Museum of Modern Art on December 15, 2014 in New York City. (Photo by Desiree Navarro/WireImage)"

Desiree NavarroBorn Peggy Doris Hawkins on September 15, 1927, in Nashville, Tennessee, the artist widely known as Margaret Keane took up art when she was ten, and eyes were always a fascination. Keane moved to San Francisco where she and Walter Keane met. At the time, they were both married to other people, but soon divorced and wed in 1955. After their divorce in 1965, Margaret moved to Honolulu, remarried, and became a Jehovah’s Witness. At the urging of her new husband, she became more assertive about her role in her partnership with Walter Keane. She spent her later years painting from the home she shared with her daughter and son in law in Napa Valley.

As a guest on the Mike Douglas Show, she was asked by the host what she enjoyed painting. “Children,” she answered, seemingly impervious to the fame and drama attached to her paintings. “Young girls, that’s usually my favorite subject.” Poodles were her favorite animals to paint, because she had two. The children in her paintings were wholly the work of her imagination, unless she was commissioned to paint specific people. She painted Liberace in front of two hundred gawkers in the lobby of a hotel, Red Skelton and his two children, Natalie Wood, and the Jerry Lewis family and their pets.