“I don’t want to die and leave specific instructions in my will to dress me in a long sleeve top because I hate my arms,” writes Marisa Meltzer. “I would like to be able to see a picture of myself and not have it ruin my day.”

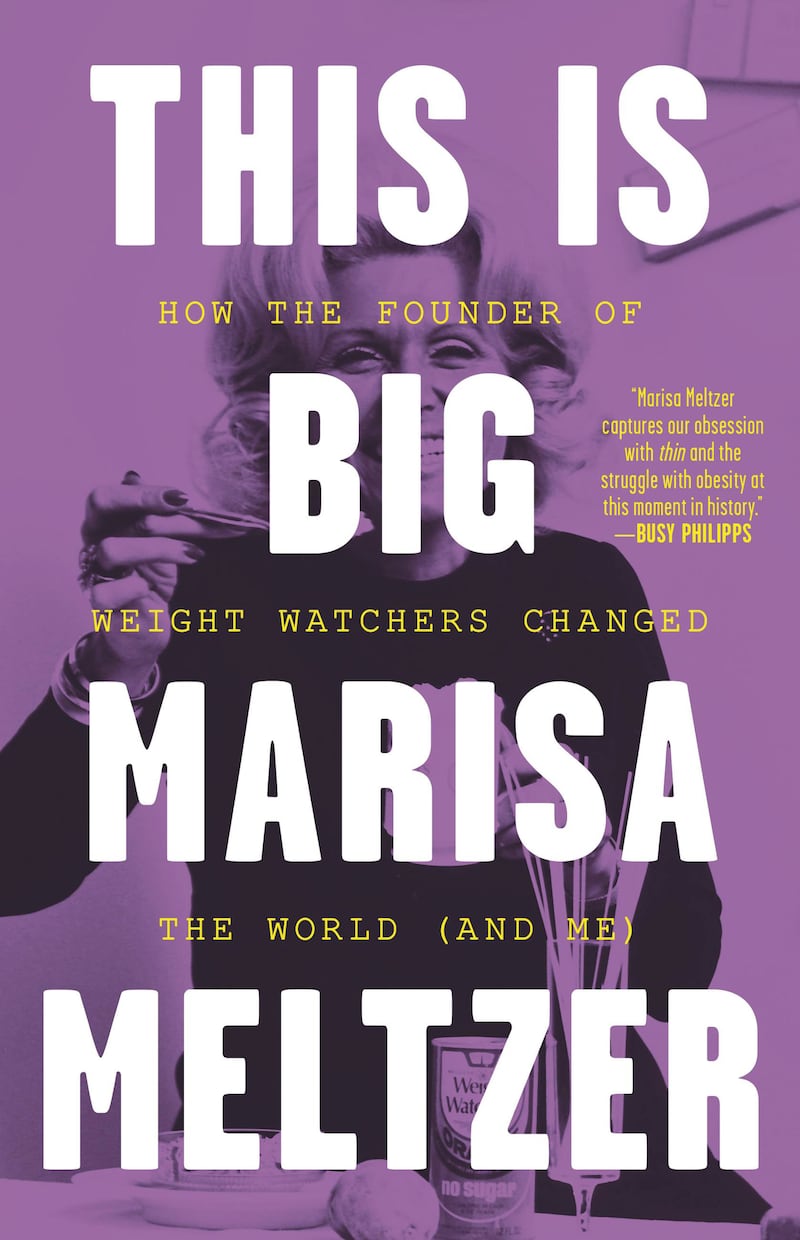

Meltzer, a journalist and author, exhumes her inner monologues around body image and shame in her new book, This is Big: How the Founder of Weight Watchers Changed the World (and Me).” She draws experiential parallels between her life and that of Jean Nidetch, a winsome housewife whose shame around her size propelled her to fight her compulsive eating and eventually found Weight Watchers.

Nidetch started a loose support group for herself and friends struggling with weight in 1961 in Queens, which grew so exponentially it became incorporated by 1963 as a dieting system and lifestyle. Nidetch was an evangelist for weight loss, and served as her own best example of what transformation could look like.

She had shed a significant amount of weight through a New York City obesity clinic, but the program’s nutritional rigor was only effective when offset by sharing the exasperation of constant dieting with others. Through community she found release, and this became the lynchpin of her brand. Meltzer noted that Nidetch “successfully had tapped into a collective anxiety of getting fat.”

Woven in with Nidetch’s journey—she died in 2015 at age 91, her triumphant mogul influence dwindling over the years as she was gradually estranged from the organization she founded—are Meltzer’s own weight struggles. “My body is tragic, but also ordinary,” she writes. “We all just accept dogs for showing up. I wish I could do that for myself.”

Meltzer unpacks the micromanaging scrutiny she faced from her parents about her weight since childhood, and more broadly examines the twisted societal expectations that skew our apprehensions of physique. Meltzer wanted to open “a dialogue about weight that doesn’t feel overly confined by how you should feel about it,” she said in a phone interview with The Daily Beast.

With unrelenting candor, she confesses to toxic social behavior (“a game I play where I scan every room to see if I’m the fattest person there”), indulging in binges (solo delivery orders where the restaurant packs four sets of plastic utensils), and enduring humiliating remarks from retail workers who brashly insisted she must be postpartum. She talks about aspiring to Amber Valleta’s clavicles but relating to Nancy Drew’s plump friend Bess Marvin.

Meltzer not only wades through dieting culture and its grim statistics, but debunks coded language around body image on a broader scale. She writes: “I say fat not as a reclamation but as a no-frills description. I hate every euphemism: curvy, plus-size, whatever.” On the phone, she expanded on this double-speak: “You see it with the bastardizations of self-care used to talk about botox and clean eating… no matter what you call it, you're still trying to deal with the way that you look or age. Calling it something else is not helping anyone out with honest discussion about the real issues.”

She added: “There’s so much pressure to be ‘a strong woman!’ these days, and to project as really confident. I understand it, but at the same time it feels like a façade, and one that is increasingly not doing anyone any favors.”

While Meltzer criticizes the societal pressures to look a certain way, she is skeptical of the body positive movement as an antidote. She writes: “our culture veers wildly between impossible standards of beauty and seemingly impossible standards of acceptance, to terrible effect to almost everyone.” She continues:“I may be my own worst critic, but my critical view is reinforced and also shaped by society. How am I supposed to not hate myself, to rise above when I’m so attuned to the cruelty of others?”

Marisa Meltzer

Courtesy Sarah ShatzMeltzer finds it unrealistic to live as though others’ perceptions have no bearing on how we see ourselves: “Loving yourself is a great idea—I wish it for everyone—but I also think that we live in a world where it can be hard to have a body, period, and if you’re someone who is fat, you’re going to be reminded of that all the time,” she stated on the phone.

She emphasized that it’s not a personal failure to be influenced by society’s messaging, however foolish it may be, when you’ve always been subjected to it. Meltzer doesn't want to shoulder the guilt for not being able to flout society’s norms conformably or authentically.

“Body acceptance says that it’s my fault that I don't feel great about my body because I haven't fully committed to loving it,” Meltzer writes, but adds that overweight people are “told to change our minds and set ourselves free, and then once we feel a little empowered, we have the old hegemonic handcuffs slapped right back on.”

As she put it in conversation: “It’s easy to pay a certain amount of lip service to body acceptance because it’s fashionable right now and shows a certain savviness, but I don't know how far that really goes.”

An avowed feminist, Meltzer expresses a certain ambivalence about Nidetch—on the one hand, she founded a company in which women reclaim their bodies, but she unequivocally encouraged women to conform to aesthetic norms and, as Meltzer writes, “keep up with the labor of femininity.”

Meltzer also notes that Nidetch’s career skyrocketed precisely during the same early 1960s period that Julia Child’s and Betty Friedan’s did. These two cultural icons were celebrated for completely different approaches to embracing womanhood, be it through gustative indulgence or bulldozing the housewife trope.

Meltzer’s own understanding from reading feminist texts was: “Good feminists, in short, do not diet.” Nonetheless, she does not fall into this camp herself: “For someone raised without religion, dieting has been a source of faith.”

That sense of faith can be a perverse one. Meltzer’s obsessiveness around dieting makes her not only keenly observant but competitive. She mentions how celebrities she has profiled as a journalist (from Busy Phillips to Karlie Kloss to Roxane Gay) or simply encountered (Padma Lakshmi, in the waiting room of a lymphatic massage parlor) have eroded her sense of self and left her feeling deflated.

The modern celebrity’s mix of “worship me”aspiration while maintaining an “I’m just like you” accessibility promotes untenable standards for body acceptance. Meltzer rarely broadens the spectrum of who else is affected by these feelings of self-consciousness, but it’s interesting when she mentions others—like a police officer in her Weight Watchers group who expresses unease about the fit of his bulletproof vest due to his size.

The book concludes on a wavering note of self-forgiveness. Meltzer doesn't tack on false epiphanies but gives herself room to keep clarifying her own needs. Her ultimate wish would be to live as though disembodied altogether, her fantasy “to be whatever size it is and for no one to see me as fat; for the social perception of fatness to cease to exist... it’s less about a hatred of fat people or my body and more about wanting to be able to live in a way where I am noticed for what I choose.”