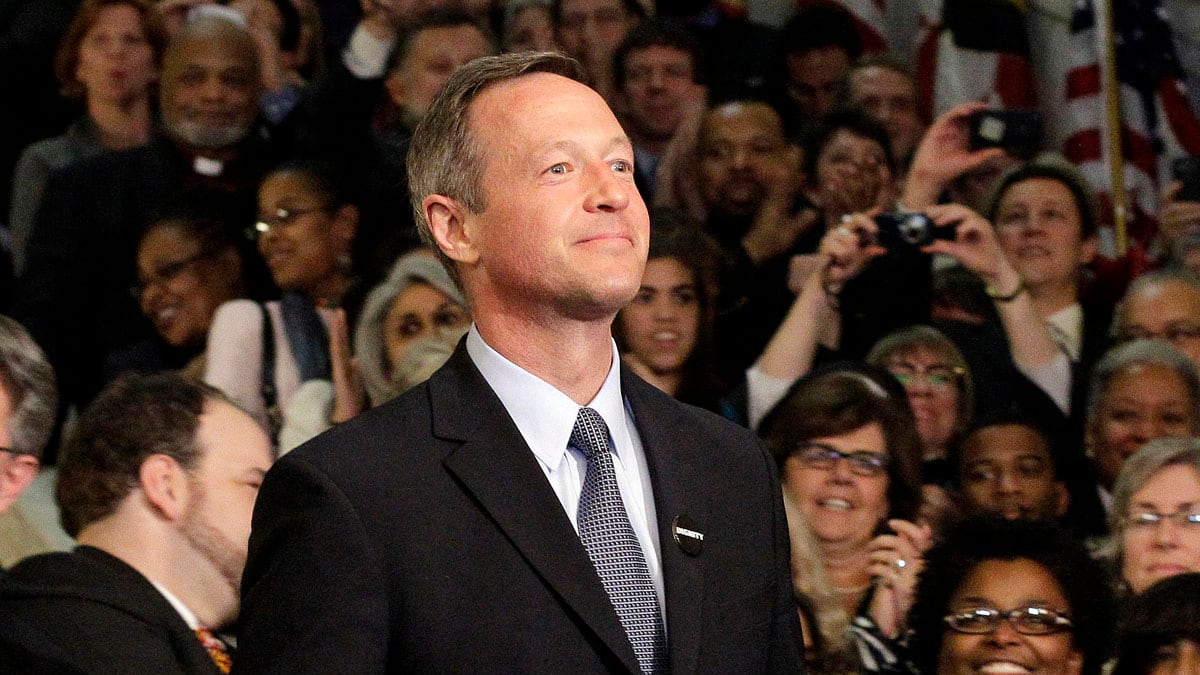

Martin O’Malley, who is busy singing President Obama’s praises in Charlotte, is also keeping one eye on the next Democratic convention—the one that gets under way in 2016.

When the Maryland governor submitted his speech—“They only gave me seven minutes”—to Obama campaign officials, he recalls, “they said I had too many applause lines. They cut it down to six,” he says, laughing.

That jockeying over his Tuesday night prime-time address underscores the delicacy of O’Malley’s position. As chairman of the Democratic Governors Association, he has become one of the president’s most visible surrogates, which in turn boosts his profile. But as he works the back rooms here at the convention, he can’t be too blatant about his future ambitions.

Chatting on the convention floor between appearances on CNN and CBS, O’Malley deflects the inevitable questions with practiced ease. “I really don’t spend a lot of time working on or focusing on 2016,” he tells me. “I’m entirely focused on helping get the president reelected.”

Yet in July he formed a national political-action committee that allows him to raise money for a future race once he completes his second and final term in Annapolis. It’s called the “O' Say Can You See” PAC, an homage to the fact that "The Star Spangled Banner” was written outside Baltimore.

O’Malley is sure to rock Charlotte in one respect: His Celtic rock band, O’Malley’s March, has a couple of gigs here this week. He plays the guitar in a sleeveless T-shirt.

It’s not hard to discern why O’Malley hears strains of “Hail to the Chief.” The post-Obama Democratic Party doesn’t have a deep bench. If Hillary Clinton runs, it changes everything, but the secretary of state keeps insisting she will step down in January and be done with politics. Joe Biden could make a bid for the top job, but he’d be 74 upon taking office.

That leaves two aggressive governors who have made a mark in their states: New York’s Andrew Cuomo and O’Malley. They have been warily circling each other—O’Malley pushed through a gay-marriage referendum in his state a year after Cuomo’s pioneering victory in Albany—while deflecting chatter about the next election.

But while O’Malley seeks out national media attention, Cuomo is almost pathologically determined to avoid it, generally refusing to speak to Washington reporters and avoiding the chat-show circuit. Cuomo is coming to Charlotte for just one day, Thursday, primarily to speak to the New York delegation, and isn’t giving a speech.

“I will go to the convention and pay my respects to Mr. Obama,” Cuomo told the Buffalo News. But, he said, “my job is being governor of the state of New York, and that's a job that's done in the state of New York.”

Cuomo is far better known than O’Malley, thanks to his famous dad, who electrified the 1984 Democratic convention with a rousing speech but never did more than flirt with a presidential bid. O’Malley, for his part, can claim this bit of reflected glory: he’s the model for the ambitious Baltimore pol Tommy Carcetti in the HBO series The Wire.

Had the Obama campaign granted him more than a few minutes, the former Baltimore mayor was unlikely to pull a Chris Christie, delivering a speech mainly about his accomplishments at home. But O’Malley admits he is anxious to talk about his Maryland record. He helped the state’s public schools win Education Week’s top ranking four years in a row, and last spring he protected some spending programs by pushing through a tax hike on $100,000-plus earners. He has also put on the November ballot a referendum to allow in-state college tuition breaks for illegal immigrants, a move that obviously appeals to Hispanic voters.

O’Malley can spit out sound bites with the best of them, as he showed in turning the conversation to a contrast between his party and the Republicans in Tampa.

“They are the party that wants to phase out Medicare, we are the party that wants to protect Medicare. They want to give bigger tax breaks to billionaires to create jobs, we believe in creating jobs they way our grandparents did, through educating, innovating and rebuilding.” (In truth, Mitt Romney isn’t suggesting a phase-out of Medicare, and Paul Ryan has proposed transforming it into a voucher program, as O’Malley well knows.)

As head of the Democratic governors, O’Malley says he “made a conscious decision to become much more involved in the national conversation.” O’Malley has become a fixture on the Sunday talk shows—in part, he says, by “being 30 minutes away from the studios.” In politics, as in real estate, location matters.

With Obama clearly struggling to recapture the kind of excitement he generated in 2008, the governor doesn’t sugarcoat the situation. “I never met a politician whose reelection was as exciting as his election,” O’Malley says. And that includes him.

In 2010, former Republican governor Bob Ehrlich, whom O’Malley had ousted four years earlier, tried to reclaim his job by running on the old Reagan question: are you better off now than you were four years ago? And the answer, says O’Malley, was no.

“I could not run in 2010 saying, ‘Vote for me, I made the eight years of awful choices of the Bush administration go away.’ But I could say, ‘We are making progress, we have a long way to go.’ Our theme was tough times, tough decisions, moving forward not backward. Sound familiar?”

Unlike Biden and other White House and campaign officials, O’Malley admits that Obama can’t claim that Americans are better off today. But he sees a lesson in his own battle back home.

O’Malley was worried when he found himself tied with Ehrlich with two months to go. “But when it came time for people to pick between two alternatives,” he says, “we ended up beating Bob Ehrlich by two touchdowns—14 points.”

Of course, O’Malley had a huge advantage at home, as Maryland is a heavily Democratic state. It may be considerably harder to sell his brand of urban liberalism in a place like Iowa. But the next few days of field-testing his message at this convention could bring him one step closer to making that decision.