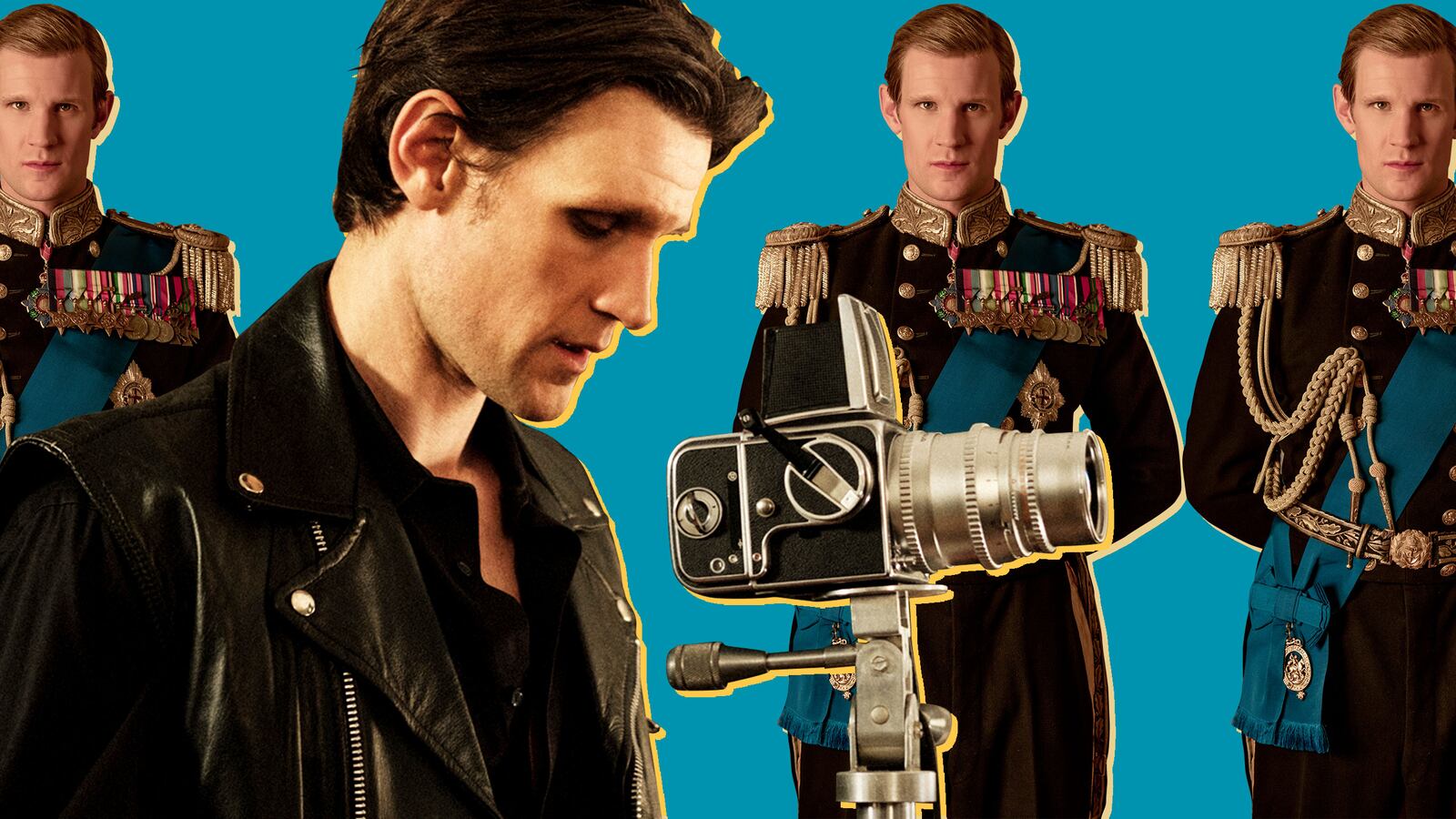

On a day when actor Matt Smith was in New York to promote his turn as iconic art provocateur Robert Mapplethorpe in a biopic that premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival, the news is, inescapably as always, dominated by the crown. And, well, The Crown.

We asked Smith, who played Prince Philip on the first two seasons of Netflix’s royal epic, if royal milestones—say, Kate Middleton giving birth to her third child the morning that we meet—feels any different after having been tangentially connected to the family as the fictionalized avatar for one of its members. Is he, too, breaking out the cigars to celebrate the news?

“I’m pleased for old Wills and Kate, man,” Smith laughs. “Pleased when any baby arrives healthily. What is he, fifth in line to the throne? He hasn’t done anything and he’s already fifth in line to the throne.”

But then there are headlines he’s more directly involved in, to do with his role on The Crown and the revelation that he was paid more than Claire Foy, who played Queen Elizabeth II, the unequivocal leading role—literally, the queen—on the series.

On the red carpet for Mapplethorpe’s premiere Monday night, Smith addressed the controversy for the first time, telling The Hollywood Reporter, “Claire is one of my best friends, and I believe that we should be paid equally and fairly and there should be equality for all. I support her completely, and I’m pleased that it was resolved and they made amends for it because that what’s needed to happen.”

When Foy had been asked about the new inferno that raged following the revelation last month, she said, “I’m surprised because I’m at the center of it, and anything that I’m at the center of like that is very, very odd, and feels very, very out of ordinary,” Foy said. “But I’m not [surprised about the interest in the story] in the sense that it was a female-led drama. I’m not surprised that people saw [the story] and went, ‘Oh, that’s a bit odd.’ But I know that Matt feels the same that I do, that it’s odd to find yourself at the center [of a story] that you didn’t particularly ask for.”

Speaking with Smith the day after he broke his silence on the matter, we ask him about that aspect of it, both finding himself in an unexpected news story stemming from financial decisions he wasn’t aware were being made, but also at the center of a vital movement and opportunity.

“It’s strange for both me and Claire,” he tells us. “We obviously didn’t expect to be brought into it because we had no knowledge of it and no knowledge of the situation. Only when you guys did. We’re great friends, and we’re very united. We just kind of very quickly went about speaking to the right people getting it resolved. Then you hope that as a society we move forward in the right ways and we learn, that we’re progressive and we make the right decisions.”

When we asked him to clarify what it means that the situation was “resolved”—if Foy was going to be retroactively paid the difference—a publicist interrupted and asked us to move on. Smith, it should be said, was thoughtful and well-intentioned while speaking on what could have been a difficult and volatile topic of conversation.

Bringing it back to the film, that describes exactly how he talks about playing Robert Mapplethorpe, navigating potential landmine conversations about playing a gay icon as a straight actor, filming nude and gay sex scenes, and channeling Mapplethorpe’s ‘70s-era gay experience with as much nimble grace, sensitivity, and—this is Mapplethorpe, after all—passion as he brings to his performance in the film.

A New York City art renegade before his death from AIDS in 1989, Mapplethorpe’s sexually explosive photography—a devious eye that exposes the beauty in the sordid—had the culturati simultaneously gasping with titillated thrill and clutching its pearls. (For every stunning portrait of Arnold Schwarzenegger, there were a dozen shots of penises in assorted, confrontational set-ups, bound-and-leathered gay men in compromising positions, and the human body bared frankly.)

“At the time he made [these pieces] in, he was sort of provocative in all the right and wrong ways,” Smith says. “And unflinchingly honest about that.”

Mapplethorpe traces the artist’s life from his arrival in New York City, to his romanticized days living with Patti Smith at the Chelsea Hotel, to his reckoning with his sexuality (and ensuing wanton exploration of it), his ascension into an art world that couldn’t decide whether to brand him obscene or embrace his daring, and, finally, his death from AIDS.

Anytime the story of a gay figure as important to the LGBTQ community’s story is put to screen, the conversation of whether he should be played by a gay actor reliably surfaces, and Smith knew that would be the case.

“I don’t buy into that, I’m afraid,” he says. “I mean, look, I understand the idea behind it and there is a level truth to having someone who’s actually gay know what it is to be gay. But then how does anyone play an alien, which we play all the time? Do we have to all turn into aliens? How does anyone play a racist or a Nazi, which we watch films about all the time? How can you be in Schindler’s List? Where do we draw the line? I don’t subscribe to that. We’re actors and we’re employed to bring our imaginations and our creative ideas and our personalities to these things.”

Taking on a Robert Mapplethorpe’s life, though, means taking on the life of a very carnal, very sexual person. To wit, Smith appears nude throughout the film—and he’s certainly not the only one—as well as takes part in racy sex scenes. We wondered how much of that Smith was already comfortable with, and how much of it was emboldened by channeling Mapplethorpe’s attitude for the part.

“You can’t make a movie about Robert Mapplethorpe without there being some cock in it,” he laughs.

“It’s Robert, and it was nudity and porn and sex and drugs, all part of his everyday life in some way, shape, or form. But yeah it’s always difficult as an actor. It’s always weird. If you had to go into The Daily Beast tomorrow and take all your clothes off, and then go in again the next day, it’s a bit weird, you know what I mean? Just, ‘Hi, me again!’”

He’s fully aware, too, that when someone buys a ticket to a Robert Mapplethorpe biopic, those are precisely the elements they want to see. “You could spend a whole film on just that part of his life,” Smith says. “Just the sex and nothing else, and it would be really interesting.”

Smith shot Mapplethorpe last June after filming wrapped for his last scenes on The Crown—an older version of Prince Philip will be played by Tobias Menzies in season three. He had six weeks to lose “quite a lot of weight” to play the lithe artist, and then even more to play him on his death bed, subscribing to a strict 1,000-calorie diet to do so. It was a balmy New York June while he was filming. “It was hot in leather, I remember that.”

Mapplethorpe marks the third time he’s dived into a role to the scrutiny of obsessive—and particular—fan bases of the characters he’s playing, following Doctor Who and The Crown; the fourth time if you count his turn as Patrick Bateman in musical version of American Psycho he performed in the West End.

“I’ve done it again,” he says, laughing at himself. “I’m about to play Charles Manson. Basically, I’m an idiot and should stop putting myself under this pressure.”

There’s always the concern that an actor will be defined by an iconic role, but Smith has repeatedly escaped that curse throughout his career. Playing a serial killer who belts torch songs in his tighty-whities and Robert Mapplethorpe as book ends to playing Prince Philip in The Crown certainly helps accomplish that.

“It’s going outside the comfort zone,” he says. “Robert wasn’t in my comfort zone. That gets me excited. It makes me feel artistic, which in a funny way is what Robert was always doing.”

Was that fun to play?

“These are always difficult. We shot this movie in 19 days,” he says. “But yeah, you know, it’s Robert Mapplethorpe! Of course it was cool. But it was hot and sweaty.”

Laughing again: “As it kind of should be, right?”