OK, so most of us are obsessed with true crime. But what happens when the true criminals want to change and reinvent their lives—and we somehow won’t let them?

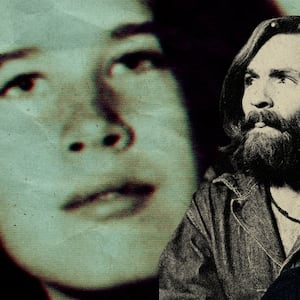

Leslie Van Houten was released from prison on parole, on July 12, 2023, after serving more than five decades for the brutal Manson family murder of Leno and Rosemary Labianca in Los Angeles in 1969. No one thought she’d ever get out—but she just did, the only Manson family member to do so. And many people aren’t happy.

The murder was committed when she was a teen, just 19, and on an acid trip. Unrepentant and under Charlie Manson’s spell, she certainly deserved prison for her heinous crime. But once inside, she went into therapy, flooded with shame, guilt and remorse, and she became determined to better herself. By all accounts she was a model prisoner, and the older she became, the less of a threat to outside society she became. Yet she was denied parole 16 times.So why is everyone seeming to deny her a future? And why can’t we envision any kind of happy ever after for her? There are no second acts in American life, Fitzgerald famously said, but I kept thinking, he’s wrong. He has to be wrong.

A member of the Board of Prison Terms commissioners, listens to Leslie Van Houten after her parole was denied 28 June 2002 at the California Institution for Women in Corona, California.

Damian Dovarganes/Getty ImagesYears back, the Manson story obsessed me into writing a novel set against the brutal murders and trial, Cruel Beautiful World, and that’s when I realized, deep in research, that the Manson girls’ part in all of this was hypnotizing us because they were such sweet-faced young girls besotted in love, even if it was with a maniac. They not only betrayed society, but they also betrayed our notions of what young girls should do and be. The fact that they were female made it even more sensational.

Some former criminals have brilliant afterlives, but still, like a stain, the idea of non-acceptance lingers. A few years ago, a close friend introduced me to a woman friend of hers. “Everyone loves her,” she said. I quickly did, too, but it wasn’t until six months later that I was told her real name—and her real fame, which I promised never to reveal. When she was 15, she had viciously murdered a friend’s mother. She served her time, she was filled with remorse, and when she was let out, she reinvented herself, with a new name, a new profession, and a huge desire to give back to society. When she did tell people the truth, she lost friends, she lost jobs, she lost potential romances. When do I get to be forgiven? she kept asking. When does it get to end?

If I couldn’t find the answer I wanted to that question in real life, I wanted it in fiction. I wanted to show that guilt and innocence and reparation don’t always look like what you want them to or how you imagine them. So, four years ago, I began to write Days of Wonder, about two 15-year-old Romeo and Juliet kids who attempt to murder the boy’s Superior Court judge father when he attempts to break them up. Hallucinating from lack of sleep, neither one remembers the crime, but one—the girl, is sent to prison. The boy, the son of the prominent judge, is released. And when the girl discovers she’s pregnant in prison, the boy has vanished, and she’s forced to give the child up. Fast forward six years when the discovery is made that her case was botched, and she’s let go, but still a felon. She changes her name, creates a new identity, and begins her struggle to find her child, her ex-lover, and to discover what really happened that night.

To research, I attended an in-person class of women who were recent parolees and on probation, led by the writer Jean Trounstine. They were going to discuss a book of mine. Of course, I was anxious. I entered the room to find a circle of 15 women putting the candy and snacks they had brought into a circle, their gazes like lasers on me. A guard standing outside. They were suspicious, closed up. Not one smiled. But as conversation haltingly started, I revealed that I didn’t know how to drive and was refused a license. One woman, then two, laughed—with me, not at me. They began to open up and their responses to my book told me more about them—because of a lover’s betrayal in the book, one woman cried so hard, I realized that betrayal had probably happened to her, too. Another was furious that that the book hadn’t provided the escape she needed.

And then I told them, I was researching a book about a young girl in prison, and I wanted to know if I could talk with them about that. “If it’s going to be like Orange Is the New Black, I’m out of here,” one woman said, “I hate that show,” and the others nodded. They were concerned that I was going to make their stories soft porn for people who find a captured woman story hot. That I would sensationalize the experience. “Not me,” I told them.

Slowly, they began to talk with me. Because I wasn’t judging. Because I was just letting them tell their truths. Yes, I got the scary stories, and yes, some prisons are much worse than others, but I also was astonished to discover that these women had made important friends in prison, and that the worst thing about prison for women was the boredom. And the best thing—if there can be a best thing in prison—were the relationships and that included the camaraderie shown in this class, the loosening of labels, so we were all just women talking about books and our lives. We’re kept so far apart from anyone in a different circumstance from us, that we can’t always know the truth about them.

But when someone like Leslie Van Houten is back into the world, we’re not in control at all. Her story doesn’t definitively end like a final podcast episode or a TV series binge finale. Instead, we ask: What if she inspires another Charlie Manson? What if she moves into our neighborhood? Is she still dangerous?

Perhaps most terrifying: while we certainly don’t want to identify with Leslie in any way—what if we should? What if Leslie’s second act, her continuing her redemption, should inspire us and show us what real atonement after a horrific crime might look like? After all my research, years of writing, and real-life interactions, I needed to show that possibility in fiction. In real-life True Crime stories, we want the crimes to not pay, or if that’s not possible and if the culprit isn’t caught, for the crimes to at least stop. We want to feel safe even if it is an illusion. The other part of True Crime is knowing that this crime is happening to someone else—certainly not to us. True Crime makes us feel calmer (and for some is an anxiety antidote), as if we are in control.

But in real life, and in my novel, the issues of good and evil are murky at best.

In Days of Wonder, my protagonist struggles with real life moral choices. Ripped from the headlines, wrong choices are often done for the right reasons, and vice versa. But in my fiction and in my real-life, guilt never goes away. We wanted to be judged not so much for our mistakes and crimes, but our attempts to redeem ourselves, right?

Fitzgerald was wrong. There are second acts, and yes, they’re harder for people with records, but they are achievable—in fiction and in real life. I made sure that my protagonist in Days of Wonder knows that and I hope Leslie Van Houten does, too.

Hopefully, someday, we all will.

# # #

Caroline Leavitt is the award-winning author of 12 novels, including the New York Times bestseller Pictures of You and Is This Tomorrow. A book critic for People magazine, her essays, articles, and stories have been included in New York magazine, “Modern Love” in The New York Times, Salon, and The Daily Beast, among others. The recipient of a New York Foundation of the Arts Award for Fiction and a Sundance Screenwriters Lab finalist, she is also the co-founder of A Mighty Blaze. Her new novel, Days of Wonder—about a young, troubled woman, early released from prison struggling to reinvent herself as she searches for the child she gave up—is published by Algonquin/Hachette. For more information visit www.carolineleavitt.com.